Jie, can you introduce yourself?

I’m Jie Han, a landscape architect based in California. Originally from China, I received my Master of Landscape Architecture from UC Berkeley. My work explores the intersection of ecology, public space, and community well-being. I’ve been fortunate to work on a variety of projects—from wetland restoration to urban plazas—many of which have been recognized by international awards such as the ASLA Honor Award, the London Design Awards, and the New York Design Awards. I’m especially drawn to sites that have been overlooked or degraded, and I see landscape architecture as a way to bring those places back to life, both environmentally and socially. For me, design is a process of care, rooted in place, and responsive to the broader challenges we face today.

What inspired you to become a landscape designer, and how did your studies at Berkeley help your vision?

I grew up close to nature—rivers, trees, and open fields were part of my daily life. I was always curious about how spaces made me feel, and I carried a sketchbook with me to draw what I saw. Sketching became a way to observe the world and understand the relationship between people and place. Later, when I moved to urban areas, I started noticing the absence of that connection and realized I wanted to design landscapes that could restore it. At Berkeley, I learned to see landscapes as dynamic ecological systems deeply connected to social contexts. The program emphasized both environmental processes and social equity, highlighting the importance of designing inclusive spaces that serve diverse communities. This interdisciplinary education introduced me to advanced research in sustainability, climate resilience, and regenerative design—insights I now integrate into my work and carry forward. I’m truly grateful for this experience.

In many of your projects, nature and people come together. How do you ensure that your designs work for both? Can you provide some examples?

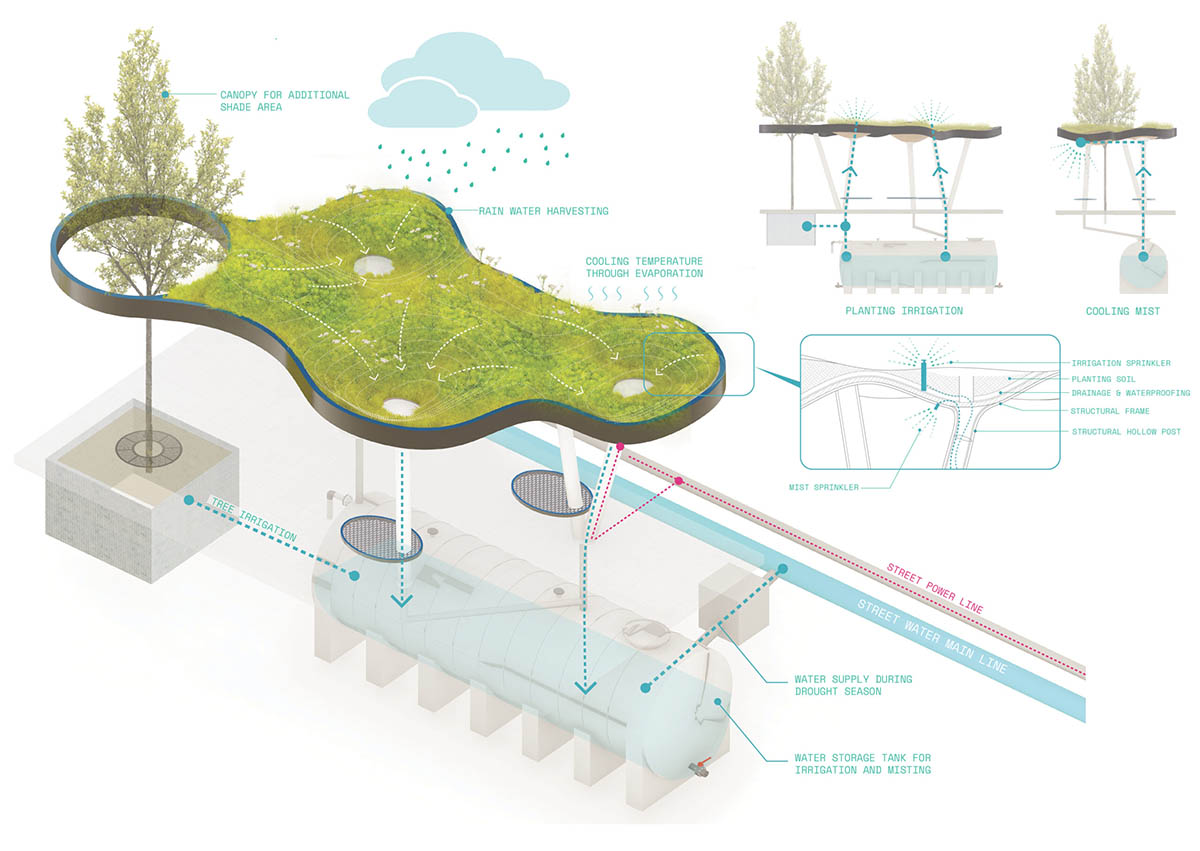

I always begin the design process by understanding the site—its ecology, history, and how people currently use or move through it—and focus on solutions that support both ecological systems and human experience. For example, as the lead designer of One Station, One Tree, One Garden, I focused on creating a climate-resilient bus station that benefits both people and nature. We integrated a green roof, tree box, and misting system to improve thermal comfort for waiting passengers while supporting urban biodiversity. Rainwater is collected through the roof and stored underground to irrigate plants sustainably. This project shows how everyday urban infrastructure can be transformed into a cooler, greener space that nurtures both community and environment.

Your design philosophy is very distinct. What makes your approach stand out from others in your field?

The environment is the foundation of all life, and I believe landscape architecture has a unique responsibility to protect and enhance it. What sets my approach apart is the way I design with nature’s regenerative power in mind. I see ecosystems as inherently resilient, and I use design to support and accelerate that resilience, bringing damaged or neglected landscapes back to health. For me, restoring the environment isn’t separate from serving people; it’s deeply connected to human well-being. My process combines ecological thinking with creativity and empathy, aiming to create landscapes that quietly regenerate over time, sustaining both biodiversity and community life.

Can you tell us a bit about the ideas behind your Recovered Wetland project? And what do you enjoy most about turning damaged or unused land into something useful and beautiful?

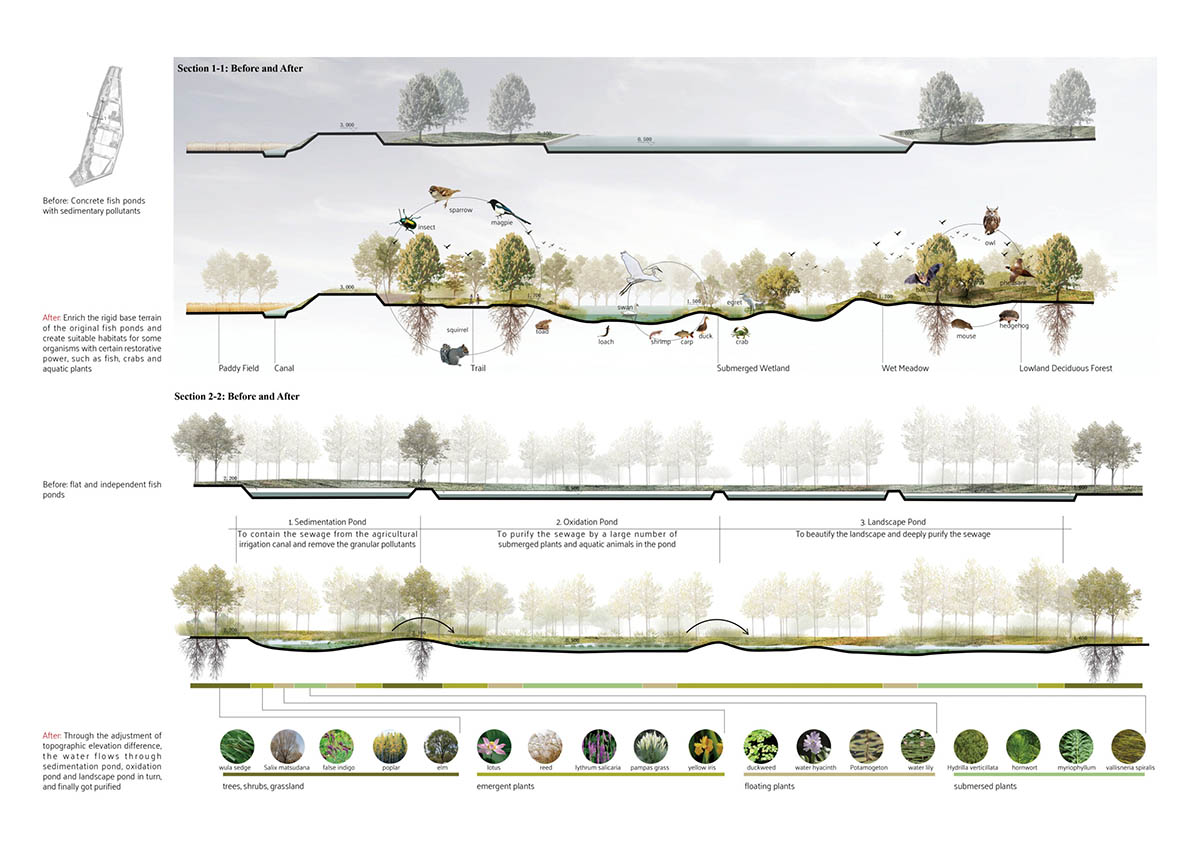

Recovered Wetland is a design proposal for a degraded wetland in Panjin, northern China. Once home to cranes, the site has suffered from habitat loss, pollution, and fragmented hydrology. The goal is to design a self-sustaining wetland ecosystem by improving water circulation, using native vegetation for phytoremediation, and reconnecting fragmented water bodies to restore natural hydrology. I also envisioned adaptive reuse of abandoned oil pumping machines as elevated walkways, allowing people to engage with the wetland while protecting sensitive habitats. I hope this initiative can help return the wetland to its former vitality. For me, the most rewarding part of this work is imagining a future where nature thrives again—and being part of that vision.

What was one of the most difficult projects you’ve worked on, and how did you solve the challenges?

One of the most challenging projects I’ve worked on recently was the A Bing Resonance Pavilion—a proposal for Erquan Square. The site is culturally significant due to its connection to the famous erhu musician A Bing, but it lacked vibrancy and meaningful public engagement. Unlike working in a natural setting, this dense, built-up environment required a delicate balance between honoring historical memory and activating a rigid, paved urban plaza. The main challenge was how to inject new life and layers of interaction into a static, hardscaped square, without erasing or overshadowing its existing cultural meaning. I focused on sound as a way to transform the sensory experience of the space. The design centered around a flexible sound pavilion made up of fourteen rotatable modules, each one designed to create varying acoustic conditions and spatial arrangements. These modules could be rotated, opened, or compacted to create intimate seating areas, immersive echo chambers, or expansive open-air theaters.

We also reimagined the A Bing sculpture as more than just a visual icon—it became an auditory anchor. A subtle sound system allowed it to play curated erhu compositions, turning the square into a living sound archive. The modules’ mobility, acoustic responsiveness, and adaptability made them ideal for the ever-changing needs of an urban public space, from quiet daily use to cultural performances and celebrations. The solution came from embracing flexibility and designing with the constraints of the urban environment in mind, resulting in a space that could respond to human activity and cultural memory, despite being surrounded by concrete and hard surfaces.

How do you hope people feel when they visit one of your designs?

I hope people feel a sense of ease and peace when they visit one of my designs. Whether they are there to rest, play, reflect, or simply pass through, I want the space to feel intuitive and welcoming—something that gently supports their presence rather than demands it. I also hope they feel connected to nature, to others, and the memory of a place. Subtly, I want the design to invite them to slow down, be present, and find comfort.

How do you think your work is influencing the field of landscape architecture?

I see my work as one small part of a larger effort within landscape architecture to address environmental and social challenges. Some of my projects have been recognized and have sparked conversations among peers and collaborators. I hope that through consistent, careful work like this, I’m helping to encourage more thoughtful, sustainable approaches in the field over time.

Is there any specific artist inspiring you?

My favorite artist is Maya Lin. I deeply admire how her work blends art, architecture, and landscape to create spaces that are both visually powerful and deeply meaningful. Her projects—like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—show how design can evoke memory, emotion, and reflection in profound ways. Maya Lin’s approach to working with natural forms and materials inspires me to create landscapes that resonate with cultural stories and environmental sensitivity.

Share with us your plans for the near future.

I’m preparing to become a licensed landscape architect to further strengthen my professional qualifications. At the same time, I will continue focusing on projects that combine ecological restoration with community engagement and resilience. I’m eager to participate in design competitions and collaborative projects that challenge me to innovate and think critically about sustainable urban landscapes. Additionally, I aim to expand my knowledge of regenerative design practices and climate resilience to better respond to environmental challenges. Beyond project work, I hope to contribute to professional networks and mentorship programs to support emerging designers and promote equity in the field.

Jie Han – www.linkedin.com/jie-han