Among other things, he mastered fencing. He has demonstrated avid competence fighting with épée. His attempts to master the clarinet proved disastrous. His teachers later claimed that, ”… there was not a gram of artistic talent in that child.”. Perhaps because he always dreamed of playing the saxophone, and not the clarinet. He enthusiastically enjoys the traditional cuisine of the region, including meals based on offal and entrails. His gourmet interests do not stop there, as he dreams of traveling in Asia on an exploratory tasting expedition, making stops at great surfing spots. Strangely, he enjoys watching the waves and other people surfing them, but has never attempted to learn how to do it himself, which he regrets and hopes to remedy in the future. In his youth, he loved drinking beer, but as he has grown older and wiser, his preferences have shifted to wine. His liver is grateful. He is a cheerful and outgoing person, despite growing up in a socialist country. Sometimes he lies, but almost always feels very bad about it. He speaks English fluently.

Born in Munich, trained in Dusseldorf, now based in Zagreb — how have these cities shaped your identity as an artist?

It feels to me that every place I’ve lived in has left a mark, created a small cognitive vivarium that is rich with adopted beliefs and borrowed convictions. Some of those reveal themselves in the most unexpected (and sometimes embarrassing) moments, others have built fundamental aspects of my personality. Having studied in Dusseldorf formed a context for the development of my art practice. In terms of therapy, I would say it provided me with tools to deal with my almost Balkan heritage. Not that I am eagerly implying that I see it solely as a traumatic asset, but… Our history is particularly opulent with tragedy. Remarkably so on any scale. And I doubt I would ever have been able to muster the courage to recognise and embrace the unique, absurd, and comedic aspects of it had I not been transplanted into a different cultural environment.

Your work navigates a fascinating space between forensic fantasy and contemporary folklore. How would you describe this tension, and what draws you to it?

I’d say there is also a fair amount of forensic folklore and contemporary fantasy involved as well! But yes, it seems I gravitate toward the irrational and fantastical. It is only fair to allow myself such indulgence, since I live in a country that is quite younger than I am. What I mean to say is that in the absence of the continuous solidity that Western Europe experienced, the periphery, the East, went through radical and violent political and cultural upheavals. Such experience created a strong notion of ephemeral social structure, of constant threat of discontinuity, and so the ever-young periphery perpetually created new mythology to reinforce its identity. It never quite ceases to disbelief its own identity, or allows one to set in fully. And at the same time, the invented and the folklore weave a fabric that forms a wishful and, more often than not, naively aggrandising self-image. Or perhaps it is just the artist’s point of view, but it does feel very rickety out here…

The materials and objects in your installations often feel deliberately chosen, almost like characters in a narrative. How do you select them — and is there a particular material you find yourself returning to?

The materials I use are a part of our wider symbolic structure, and they become a part of the grammar of every artwork. They allow significance to seep in and create the tension within the narrative of the work. They disrupt what would otherwise be a rather dull display of mundane object assemblage. So choosing them is a first step. Falling in love with the heritage and significance of a specific material, and then building layers of meaning upon it. So I would completely agree, creating an artwork for me is almost analogous to the process of casting the characters in a movie or a theatre. Choosing ones that will play off each other’s strengths and reinforcing the dramatic tensions of the artwork. If I had to pick a singular material that I would take to a deserted island, I think it would be a pile of bones. They seem to be everywhere and such an integral part of my material identity, ranging from mildly repressed Catholic ossuaries and reliquaries, to mass graves and the subsequent memorials created, banned, and revived by successive regimes and governments – they feel very… omnipresent and talkative.

You often work with layered, sometimes mystically charged narratives. Are there recurring themes or motifs that continue to surface in your practice?

I think suffering is always there. Either glorified or implied or overbearing or forgotten, collective or individual, but it lurks somewhere in the work, always. Quite understandable when I consider that my childhood fantasy world is simultaneously populated with, at that time, clandestine, catholic obsession with suffering. The Martyrs. The Crusaders. Crucifixions, flagellations, flaying, and torture of every kind – everything is in there. The numerous Turks impaling everyone en masse in their path, while relentlessly fighting for supremacy within my imagination against the legions of communist war heroes and the hangings, mass executions and nazi puppet regime concentration camps. All the monuments to all the battles, where the significance of the event is defined by the numerical value of lives lost. Propaganda movies where the good triumphs, but the depiction of the evil is so much more obsessively intricate. So much more vulgar in its display of violence. And all this, combined and intertwined, culminates in the wars and ethnic cleansings of the 90s. Nobody comes out unscathed from the periphery.

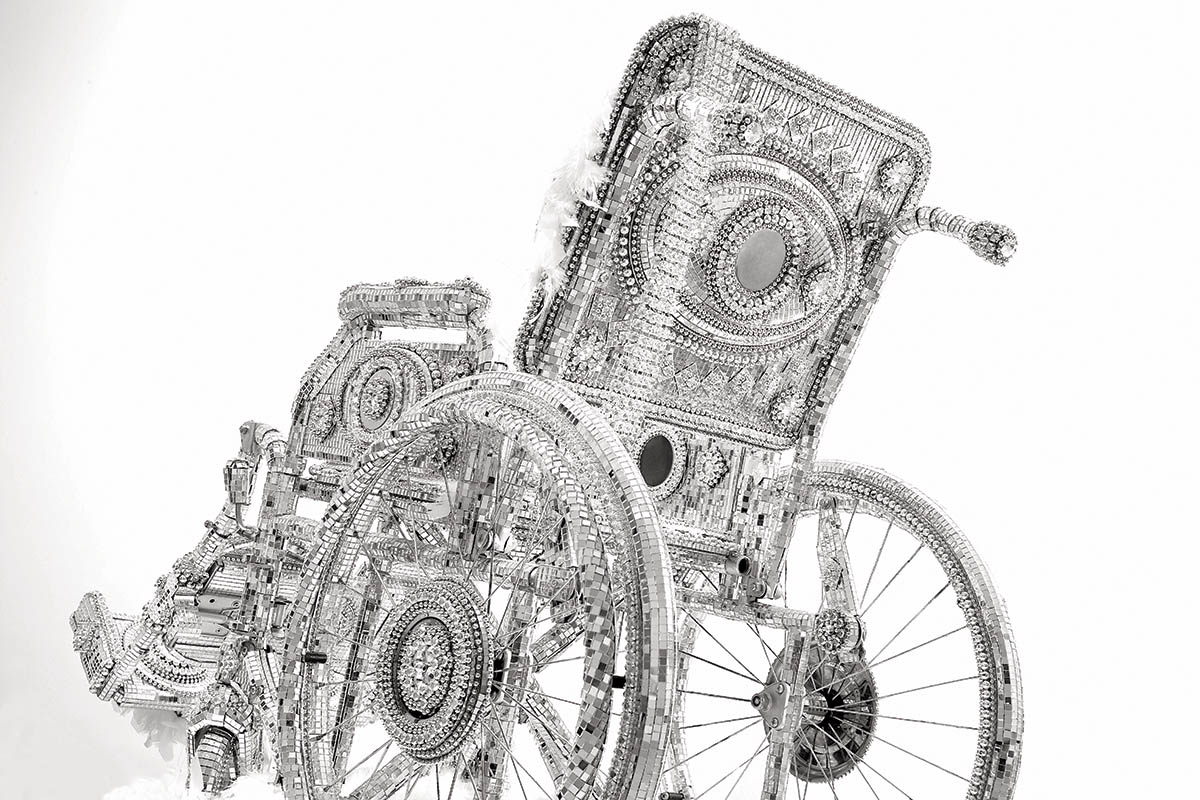

Can you tell me more about the work “Wheelchair” from 2003? In which context was it created? Was it part of a larger series?

It was a part of a larger series called Discoware, a large body of work encompassing every imaginable mobility aid or immobilisation device, any object that burdened the observer with a feeling of apprehension. These objects were blinged out to a ridiculous level. Mirrors, crystals, strass, glitter, sequins, rhinestones… They were distasteful. At the time I created that series, my country was experiencing an economic boom. Boom is perhaps a too boisterous term. But we did experience the upheaval of hope. Of hope that we will be pulled into the prosperity of the democracies of the Western world. And with lightning speed, a taste for luxury became an obsession. It became a measure of success. Of worth. And as soon as its existence has become known to us, we craved it wholeheartedly and succumbed to it desperately. The idea was, on one hand, to draw the dread that we would rather forget back to the front. To force it upon the viewer. And on the other hand, to create the hysterical objects of distasteful greed. To create a functioning art object in a distasteful manner. A trap for the Les Nouveaux Riches.. 🙂

What does a typical day in your studio look like?

It is a never-ceasing parade of unparalleled, glorious intellectual insights and artistic breakthroughs! Happiness radiates from every corner of my creative haven, and unicorns of love dance over the creative rainbows, as glitter of joy rains everywhere. Everything I touch turns into… Honestly, the days are filled with me succumbing to one or the other aspect of my OCD. Desperately trying to keep the ever encroaching chaos of materials, notes, sketches, and possibilities in a barely functioning order! And it always starts with… coffee!!!

Do you follow a structured routine, or is your process more intuitive?

I try every day. I try to form a structured routine that I will rigorously adhere to and maximise my efficiency. But eventually, something fails. Something falls apart, and I improvise, and on top of that improvisation, I improvise again. It seems to me that I am amazingly successful in creating a structured routine of perpetual improvisation.

You currently live and work in Zagreb. How does the atmosphere of the city influence your daily life — and perhaps your art?

Zagreb is an amazing place, if somewhat of a layered cake. It’s medieval parts seep into urban planning areas under the Habsburgs, which in turn border sharply with the new and modern of the socialist expansion. Sometimes these parts violently clash, creating ideological ramparts on opposite sides of the streets. Sometimes, parts become surrounded, isolated, and encroached by the architectural manifestations of subsequent ideologies. And then, like sprinkles on the cake, interpolations of the ’90s and 00s appear. Unforeseen and uninvited, here and there. Almost like cancerous tissues that are confronted with limited space for expansion – devour a house, or a block, and then start to decay, often quicker than the surrounding historical membranes. And through all that warfare, it appears that we chose to forget how to maintain our past achievements. We build new and abandon the existing with childish excitement. And after a while, we remember, we reminisce on how glorious and charming and proud the past was, and then we try to revive it. Restore it. Sometimes we succeed, but even that emphasises the patchwork character of our city and ourselves. It is a periphery that still tries to fight off the prominence of provincialism.

The opening of your exhibition at the Trotoar Gallery in Zagreb was on May 22nd — what are you showing in the exhibition?

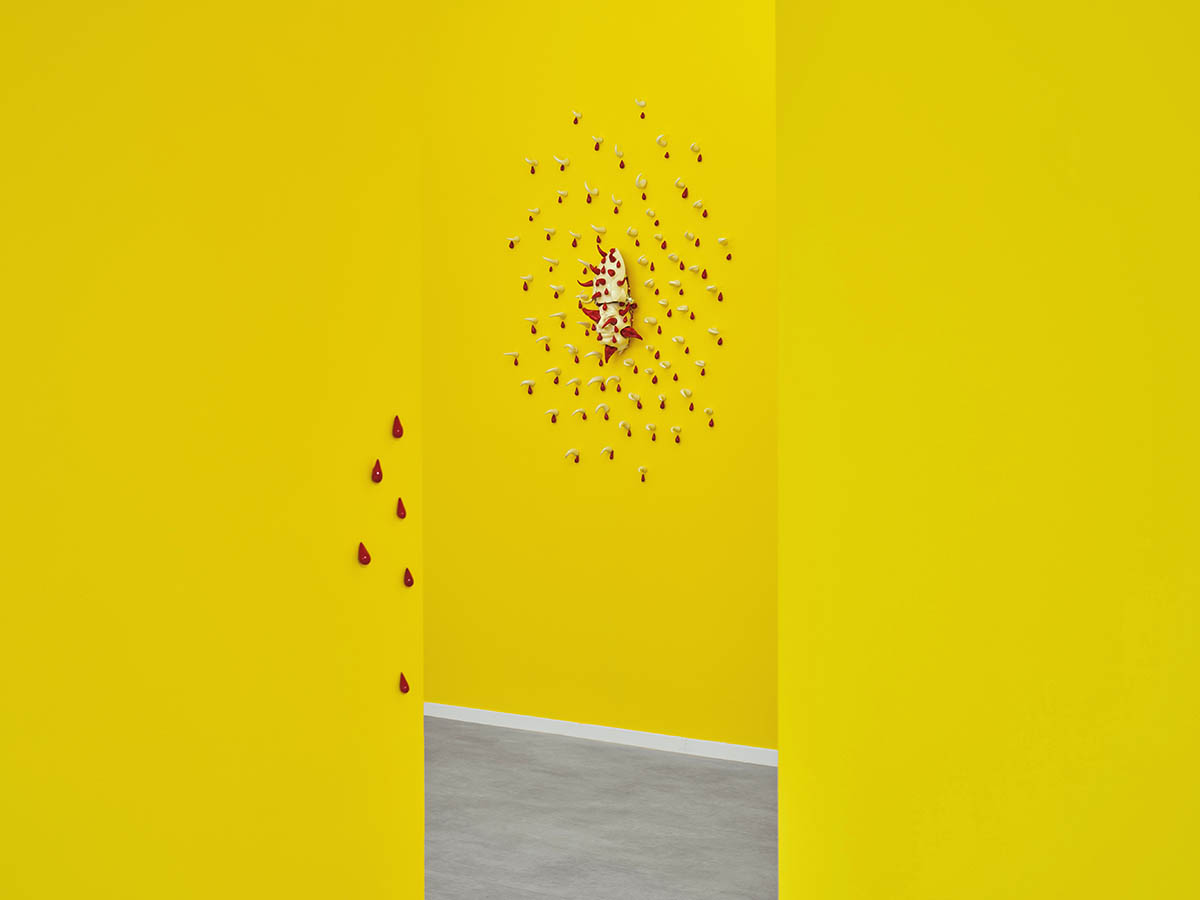

Degenerates, monsters, and traitors. It is the title of the exhibition, and it refers to a peasant uprising in 1573. It has been officially interpreted as a proto-socialist event during the socialist years. As we were taught that the struggle for workers‘ rights is almost eternal, and predates the 20th century. More recently, it has been interpreted as our centuries-old struggle to destroy the yoke of the foreign rulers, conquerors, and oppressors to obtain independence. But common to those and all other interpretations is a tendency to demonise the other. To see the other, as the absolute, simplified, reduced to the essence – evil. It is a very human ability – to dehumanise another human being. It allows us to functionally wage war. To conduct a conflict with higher efficiency, otherwise we would be inclined to empathise with the other, however unlikely it would be in this case. The works, the protagonists, are sculptural assemblages consisting of a multitude of ceramic figurative parts, combined with specific found materials, like knotted ropes, broken bottles and caps, all nailed firmly together to form all the present horrific entities. It is a carnivalesque surreal landscape entirely populated by the grotesque representations of absolute evil, either triumphant or succumbing to the swift revolutionary justice or decaying from within. So, to refer to former questions for a bit. Yes – there is a lot of implied and also quite graphic suffering.

Also, there is the underlying creation of the national myth, as the interpretation of the uprising proved to be very flexible and its prominence in the history books has been resilient over the recent decades, providing fundamental conviction of our ability to triumph over evil. But there is an underlying aspect to it that makes the whole construct very contemporary. As the gap between social strata is increasing, the difference between the rich and the middle class is becoming hyperfeudal. And even though the myth of constant social mobility persists in our societies, it seems more often like wishful thinking than a common practice. But our seclusion from the opposing opinion through social media, dissatisfaction with our state of personal prosperity, constant pressure to live our lives according to materialistic principles (human rights be damned) and tendency of oversimplification of complex problems – eventually births the growing number of populist imbeciles. And they are eager to provide us with any number of horrifying monsters.

Exhibition: Kristian Kožul – Degenerates, Monsters, and Traitors (1573)

Exhibition duration: 22 May – 06 September 2025

Address and contact:

Trotoar Gallery

Mesnička 7, Zagreb, Croatia

www.trotoar-galerija.hr

www.instagram.com/trotoar.gallery/

Kristian Kožul – www.instagram.com/kristian_kozul/