Lisa, could you share more about your background and how you approach your curatorial practice?

I’ve always had a preference for photography. One of my elementary school teachers introduced me to it by explaining what a darkroom is, and we even worked in one. That experience stuck with me. In my curatorial practice, I’ve been focusing on photography for many years, although not exclusively, but very prominently.

I’ve been curating exhibitions and publishing, and writing books for many years. I’ve always been involved in institutional contexts, which, sadly, will come to a close at the end of August this year at Kunstforum, and on the other hand, I’ve consistently engaged in freelance curatorial work. I am open to new and challenging curatorial work.

It was kind of a natural fit for the GMUNDEN.PHOTO festival came to me. This year, I’m curating it for the third time, and for the first time, it will be a monographic exhibition; previous editions featured group exhibitions. This kind of curatorial work is always especially challenging for me. I’m not saying that institutional work isn’t challenging- it absolutely can be, but I enjoy challenging myself with new spaces, contexts, and audiences. And that’s exactly what GMUNDEN.PHOTO is about: reaching people who may not have previously encountered contemporary art.

I believe contemporary art is incredibly relevant to society. It speaks to urgent topics, often long before those topics reach mainstream discourse.

You mentioned your interest in photography; it’s a medium you curate a lot. Do you photograph yourself?

I have a complicated relationship with images. I think you can imagine that, given my profession.

I wouldn’t consider my photography artistic at all. I leave that to the people who do photography. Instead of photography, I would say that writing is my artistic practice. That’s where I express myself creatively. I also write lyrical texts, not just academic writing, and someday, I’ll write a fictional book. I do publish a lot, mostly in the context of exhibitions, but writing feels like my domain when it comes to personal creative work.

I got invited to write critical texts as well, but I think curatorial ethics are just not allowing me to do that. I am the one who is preparing the stage for the art and the artist.

You started your studies in Vienna but also spent some time in Rome. I find it interesting concerning VALIE EXPORT and the kind of „Viennese woman“ she represents. Do you remember your first encounter with her work?

Honestly, I can’t say when I first encountered her work. I feel like it was always just there. But I do remember that as a teenager I saw an exhibition at Kunstforum, long before I worked there as a curator, and I remember this bathtub filled with oil by VALIE EXPORT; that might have been my first direct encounter.

Of course, once I started studying art history in Vienna, I came across all of her legendary performances from the late 1960s, especially her feminist work. Her career spans almost six decades. She’s an absolute cornerstone of Austrian and international art history. It was truly an honor that she agreed to work with us for this year’s GMUNDEN.PHOTO edition.

Her longevity is something of such importance also for today’s art discourse. How would you define “contemporary art”? It’s a term we use so often, especially post-2000s, but everyone seems to understand it slightly differently.

That’s such an important question. For me, “contemporary art” doesn’t only refer to visual art. I include contemporary literature, for example. What defines it for me is how it changes the way I look at things.

If I encounter contemporary art that really grabs me, emotionally and intellectually, then I notice how, afterward, I look at the world differently. People, situations, and even just walking down the street feel altered by the experience. That’s when art is strongest; it just follows you, and it lingers. I think that’s also true for great literature. These are encounters that stay with you and add layers of knowledge. I call it “additive knowledge.”

Contemporary art helps us navigate the multitude of perspectives that exist today, and embracing those perspectives is, I think, absolutely central to democracy.

That connects to bringing VALIE EXPORT’s work to places like Gmunden and how you’re fostering new dialogues with people who might not normally engage with art. VALIE EXPORT’s work always feels so timely, so resonant, even decades later. For instance, her performance Tapp und Tastkino, where she wore a box over her chest and invited strangers to reach in and touch her breasts for 12 seconds, is still so unsettling and current. The message still hits hard, even 60 years later.

Exactly. I asked VALIE in our interview for the publication whether she still felt the same rage she felt in the 1960s and 1970s. And she said, “Of course I do.” But she also said she expects this rage now from younger feminists: to go out, to claim their rights, to shine a light on how female bodies are still objectified in media, and all the other problems we face.

Yes, things have changed, but not in a linear way. Social media, for example, has radically shifted how we present and see ourselves. VALIE EXPORT addressed those image politics decades ago; she was way ahead of her time.

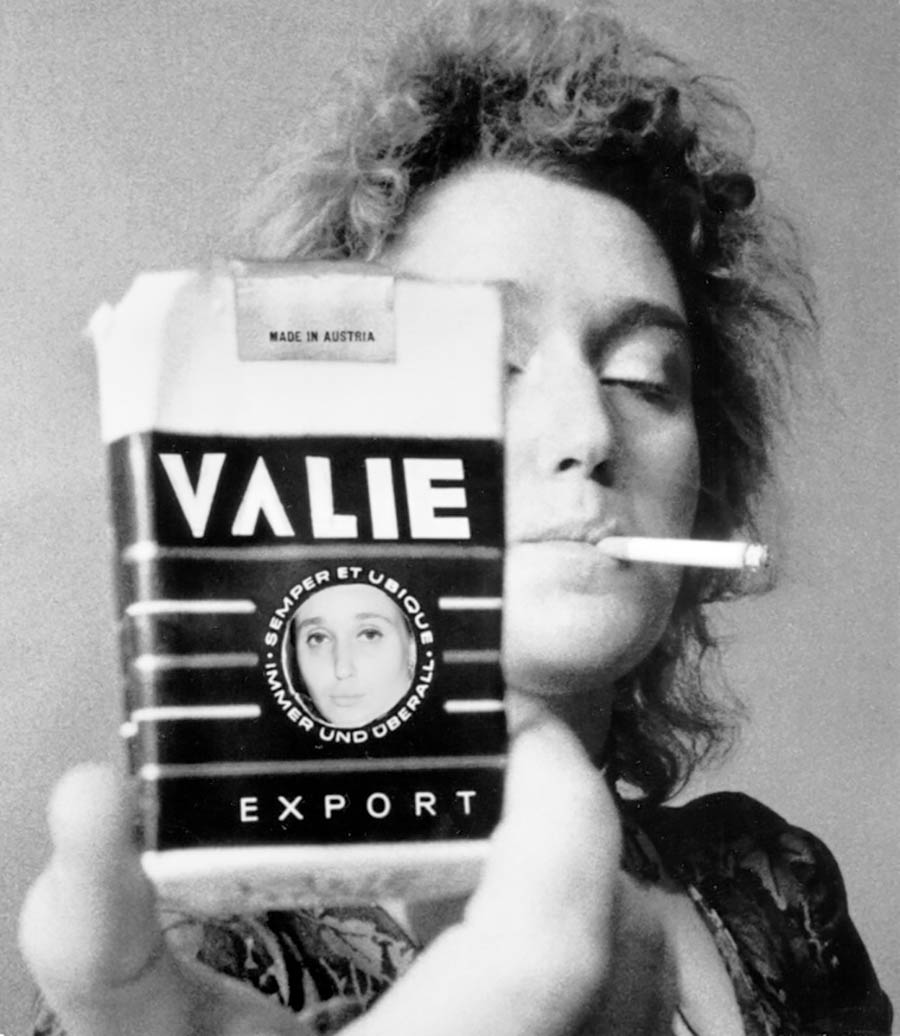

Even her name, which she adopted in 1967, VALIE EXPORT, in all caps, is a bold gesture. She took an Austrian cigarette brand, “Smart Export,” and replaced “Smart” with “VALIE.” That was her branding moment, her entry into the art world.

I learned only last summer that she’s also a mother. It reframed everything again for my understanding of her work. And the linguistic element of her name, EXPORT, it’s brilliant. The layers of meaning are endless. She’s not just Austrian or European; she’s one of the very few female artists to achieve international recognition during her lifetime. Which brings me to a more technical question: how did you go about selecting the works for the current exhibition? I noticed that some photographs are exhibited on a smaller scale, while others are dramatically large. How did you make those curatorial decisions?

The selection process was a collaboration with VALIE’s assistants, Sigrid Guggenberger and Nicole Toferer. Together, we reviewed the archival material and thought about how we wanted to tell this story anew.

The decision to work with different formats, some enlarged, some intimate, was about creating a dynamic rhythm in the exhibition space. In the exhibition, it is not just about chronology or medium, but about experience. The scale shifts force you to change your posture, your gaze, and your proximity. This is also a way to reflect the core of VALIE EXPORT’s work: embodiment, presence, and confrontation.

It was important to us that the exhibition didn’t feel like a “greatest hits” show but something that resonates now: something that carries her rage, clarity, and precision into this moment. Because she still has things to say.

So, we used all of these ship freight containers as individual structures, almost like single rooms, to experience her iconic performances. One important decision we made for the first time was to work not just with the interior of the containers, but also with their outer surfaces. That’s how we arrived at the idea of installing the Körperkonfigurationen („Body Configurations“) series on the exterior skins. These are works that she created throughout the 1970s and 80s, nearly over a decade, where she staged her own body concerning representational architecture in the city, architecture that often symbolizes power and authority.

In these works, her body becomes almost like an attacking or resistant medium, confronting these structures. So it made perfect sense to use these images on the outsides of the containers to make them interact with the urban space directly, just like the original works intended. This part of the exhibition was presented in the so-called Kunstquartier Stadtgarten, which is the former garden of the city of Gmunden.

For the second year in a row, we were also able to extend the exhibition to Kunsthaus BLAUE BUTTER, a cargo hall where we focused on the more poetic, language-oriented aspects of her work. That’s something that has always fascinated me, that her practice can be incredibly bold, even brutal and fearless, but at the same time, incredibly delicate and poetic. For instance, in some of the videos, you see her performing love lyrics in front of the camera. There’s a playfulness to it, something in the tradition of Austrian concrete poetry. She moves fluidly between media, whether it’s performance, photography, or language.

In German, I like to say that her work is “hart und zart.” In English, maybe we’d say “tough and tender“.

This duality: the extreme between the brutal and the fragile, is something I think is essential to her work. Sometimes her performances might appear radical, but we have to ask: is it that we perceive them as radical because they challenge expectations of femininity?

Especially in the context of the 1950s and 60s, when women were expected to behave a certain way, she was doing something radically different. Maybe it’s not about radicality per se, but about not coding the work in a way that fits conventional gender expectations. Take, for example, her piece “Aktionshose: Genitalpanik”. Many people misremember it; they think she stormed into a cinema with a weapon. But in fact, the original performance happened in a cinema where she walked among the audience wearing trousers with an open crotch, a provocation that directly confronted the passive, voyeuristic relationship of the male gaze.

The famous image with the weapon was a later staged photograph, not part of the live action. For our exhibition, we enlarged that image into a huge poster. And in front of it, we installed a work by a young artist named Deborah Hazler. She’s a performance and textile artist who deals explicitly with the vulva in her work. Her installation, “Pleasure Army,” consists of several clitoris sculptures made of sheep wool. It’s a humorous and powerful counterpoint, expanding the discourse to include menstruation, menopause, and childbirth. These topics are gradually entering the public discourse, but the process is still slow.

Interestingly, VALIE does not necessarily want to be labeled a feminist artist even though so much of her work operates in that space. Take the performance “Aus der Mappe der Hundigkeit” from 1968, for instance, where she leads Peter Weibel on a leash through the city streets. Many people misinterpret it as a role reversal between man and woman. But both of them said the work was also about the relationship between humans and animals.

Her work never delivers simple, placative messages. It’s layered. It can flip from soft to hard, from poetic to aggressive, in a split second. That complexity makes it so powerful.

We often talk about VALIE EXPORT as a singular figure, an icon. But I think it’s important to highlight the collective and relational aspects of her practice as well. Many of the photographs of her performances were taken by friends, colleagues, and people from her circle.

When we were compiling the publication for the exhibition, we had many names come up. People who had documented her work early on. That sense of shared effort was very present. In the 1960s, being a woman artist was already difficult.

And although it’s often presented as though they were in rivalry, for example, one got a professorship, and the other didn’t, I’m not so sure. We often project these competitive narratives onto women that we don’t onto male artists, who are allowed to form groups, cliques, and even „brotherhoods.“

Still, the structural discrimination was real. These artists weren’t exhibited, collected, or supported in the same way as their male colleagues. VALIE EXPORT, Maria Lassnig, and Kiki Kogelnik, to me, these are the foundational figures of postwar Austrian art history, especially from a female perspective. And they were all unique, with distinct approaches. VALIE EXPORT, in particular, had the most politically explicit and socially critical message of the three. While Kogelnik and Lassnig focused on different aspects, Kogelnik on pop-inflected feminism and Lassnig on self-perception and the body.

EXPORT’s work directly challenged patriarchal structures. And yet she never saw herself as a victim. She used what she had: her body, her voice, and her network to create art that changed things.

GMUNDEN.PHOTO 2025

VALIE EXPORT: INS AUGE STECHEN/ HITTING THE EYE

Curated by: Lisa Ortner-Kreil

Duration: June 28 – August 10, 2025

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday, 1:00–7:00 PM

Location: KunstQuartier Stadtgarten Gmunden & Kunsthaus Blaue Butter, Johann-Tagwerker-Straße 12, 4810 Gmunden

More information: www.gmunden.photo, www.instagram.com/gmunden.photo

Lisa Ortner-Kreil is an art historian and literary scholar. After working at Vienna’s Museumsquartier, the Albertina Vienna, and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, she has been a curator at the Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien since 2011. In addition to teaching at the University of Vienna and the University of Applied Arts Vienna, she is the editor of numerous publications on modern and contemporary art. Her work focuses on interfaces and border areas of the arts, especially image/text, transmedia artistic practices, and pop culture. She is one of the founders of “art hoc projects”. www.instagram.com/lisaortnerkreil, www.arthocprojects.at

VALIE EXPORT was born as Waltraud Lehner in 1940 in Linz, where she attended the School for the Arts and Crafts. In 1964 she graduated from HBLVA for Textile Industry in Vienna. Since 1967 she has been going by the name VALIE EXPORT, an artistic concept and logo. She works with a wide range of media and caught the attention in the 1960s and 70s with actions in public space that belonged to the field of performance and to media art and were developed from a feminist perspective. www.valieexport.at