How did Khrais–Tërshana come to life? What is exciting about the different art markets you want to be part of?

Khrais–Tërshana is an art dealership and production studio based in London and operating between Tirana and Krakow. It is an interesting triangle for us. Poland has a confident, visible, and institutionally anchored art scene; the market shows strong momentum and has expanded dramatically since the early 2000s. The situation in Albania is different; there are numerous new project spaces and non-profit institutions offering great programmes, but so far, there’s been little action towards building an infrastructure. There are almost no commercial galleries or dealerships operating at an international level, so it’s a great opportunity to test new ways of doing things. London is London; it has a long-established, highly functioning art market, yet remains a place where new and alternative models are constantly being tested. Working here has shown me what can succeed and what fails, and I find it interesting to bring those insights back home.

Lisja, tell us about your background. You are coming from a different discipline than art?

I was born in Tirana and moved to London in 2018 to attend law school. In 2022, after graduating and while preparing for the Solicitor Qualifying Exam, I began to question the path I was on. Almost as a personal dare, I applied to Central Saint Martins. Given my corporate background, I didn’t have high hopes, but that contrast turned out to be my strength. What kind of lawyer wants to join a self-proclaimed “factory for troublemakers”? In June 2022, less than a month before the SQE, I received my acceptance letter. I still sat the law exam, passed it, and two months later walked into art school.

The course I attended, MA Innovation Management, was a space created to help us develop the tools, creative competencies, and strategies to drive innovation in and across a chosen field. I focused on contemporary art, and so did only one other person in the course, my co-founder, Sofian Khrais. We worked together on a couple of projects and pursued parallel research into the contemporary art ecosystem.

Did you have a mentor, or what was the most important thing you learned?

Funnily enough, the most formative part of my studies came from a course I never officially took. Every Wednesday at 10 a.m. I joined Professor Daniel Rubinstein’s MA Contemporary Photography, Philosophy, and Practice lecture. It was an intimate room of 10 students or so, and I prepared for it just like everyone else. The ritual felt even more significant precisely because I wasn’t allowed to be there. What I was learning was secret knowledge.

How different is it to work in a law context compared to an art dealership?

Law requires you to be direct, transactional, and often a bit distant. In art, conversations are rarely just formal; they’re intimate conversations. You need to tell stories, listen deeply, and make people feel their taste and choices are shaping something larger than themselves. One instinct I’ve carried over from law is the commitment to fairness. As a dealer, you’re protecting the interests of the artist as much as those of the collector, and without trust, authority, and balance, those interests can easily pull in different directions. Having a dealer in the middle helps in preventing miscommunications, and unlike a lawyer, you have to act as a mediator who makes sure both sides feel supported. It’s delicate work.

At the same time, when I look at this event and your previous projects, there is a strong element of curation in your selection of artists and artworks; it’s not just market-oriented. Would you say there is an element of curation in your position, considering I’ve previously worked as a curator?

Absolutely. I aim to position myself as both curator and dealer. Khrais – Tërshana operates at the intersection of practice and production with a future-facing approach to care, circulation, and collaboration. Yes, we link artists to collectors and source work for private clients, but we also aim to produce ambitious projects for museums, biennials, and cultural organisations. Each side of the art ecosystem carries its own value, and I believe working across both allows each angle of my practice to continually inform and strengthen the other.

I think it is very important that you are coming from an international view; you are adapting something from an older market to a new market. There are a lot of differences, of course, but the art market could work on the same principles and in different contexts. How important is this thinking globally for you?

Travelling is essential for me, and I collect ideas everywhere I go. For example, I spent some time in Mexico City earlier this year, and it’s one of the most exciting art scenes in the world. I was invited to speak on a panel at JO-HS Gallery about the art market alongside curator and art consultant Polina Stroganova and Andrea Bustillos Duhart, who was recently appointed curator of Casa Wabi. The discussion was critical yet friendly, and the audience felt comfortable joining in spontaneously and breaking away from the typical hierarchical format I am familiar with in Europe. It made me realise how much London might have tempered my Mediterranean spirit, and I loved it all the more for that. After the talk, Andrea invited me to an annual art auction organised by Terremoto. It was the most fun I’ve had at an art evening; there was so much genuine interest and support. The Mexican way of loudly celebrating life and art greatly inspired me to bring that same energy to the scene in Albania.

What are your aims when organizing an auction?

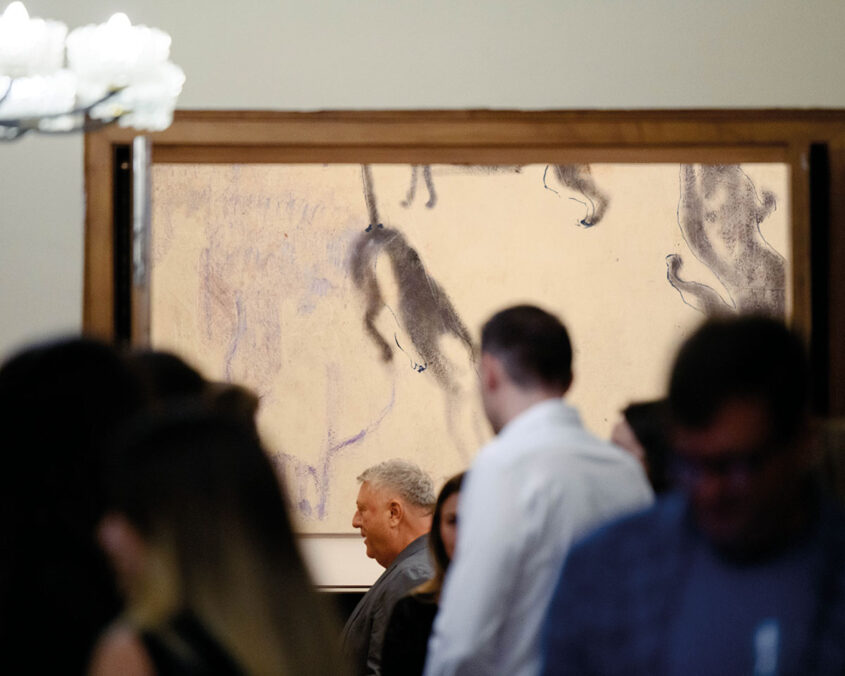

Many people have asked why I chose an auction for the launch event over a standard exhibition. In an auction, each bid is a double gesture. On the one hand, it’s an act of valuation: you are co-creating the market price of a work in real time. On the other hand, it’s a public declaration of taste. By raising a paddle, you’re not only saying “I think this is worth X” but also “this is the kind of art I want to be seen supporting.” This visibility is powerful in my mission to activate a new circle in Tirana of contemporary art supporters. I personally invited around 150 guests from different generations and industries — some who have already engaged with contemporary art, and many others probably encountering it seriously for the first time.

At the same time, it was different from your regular conference room and clinical lighting auction. We hosted in a garden on the last evening of Mediterranean summer; the auctioneer and the DJ were positioned inside a drained fountain; there were Negronis and tapas; laughter and cheering. The evening began with a conversation on the historic role of collectors and the social impact of their support, especially in a place like Albania, where every acquisition can genuinely shift an artist’s trajectory and should be celebrated as such.

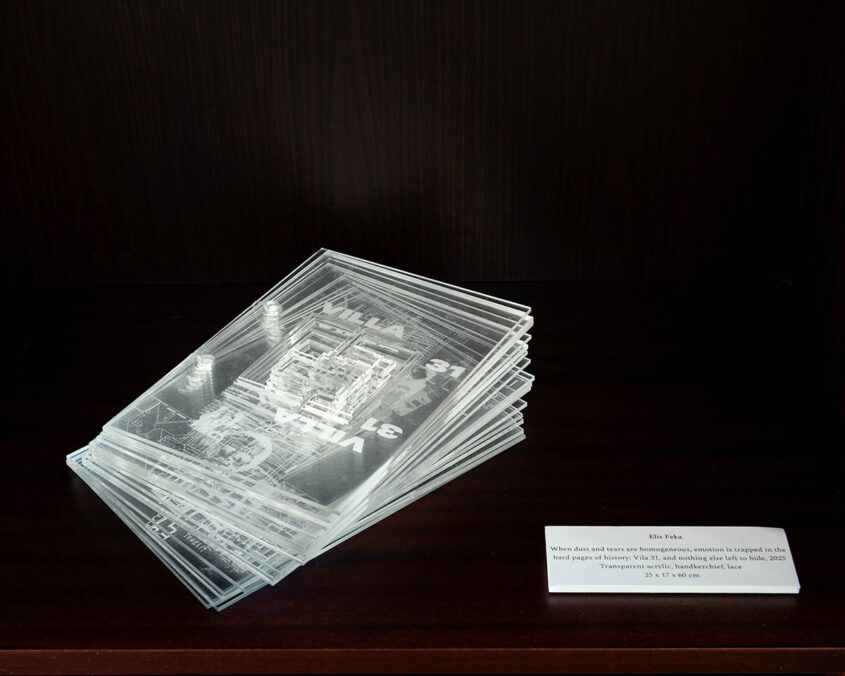

The auction took place in Villa 31 x Art Explora in Tirana. What is so special about this place, and what about its area? Is it „alternative“?

Vila 31 x Art Explora sits in a central neighbourhood that is both corporate by day and vibrant at night, so it’s not necessarily “alternative” in the usual sense. It was once home to Albania’s former communist dictator Enver Hoxha, and it remained closed to the public for decades. As of 2025, it’s open to the public, regularly hosts cultural programmes, but also home to around 8 artists in residence.

I liked the tension of hosting a free-market art auction in a space once defined by censorship. Some members of the local art scene have vocally disagreed with this choice, and that’s fine. Productive debates and criticism are essential contributions to institutional discourse, dare I say, even more so than collective praise. I remain deeply grateful to artistic director Nita Deda, who believed in my proposal from our very first conversation and entrusted me with the freedom to realise it exactly as I envisioned. Tirana is lucky to have a leader like her.

Where there going to be artists present at the auction as well?

No participating artists were invited. Mainly because, well, it’s a bit awkward for everyone involved. But I also wouldn’t want my artists to start comparing themselves with each other. There really is no need to create that pressure.

Why was the event title MARA? It sounds both neutral and romantic as a name.

This is an evening dedicated to those visionary collectors in art history whose taste, care, and support are capable of shaping new art movements, contextualising practices, and building artist careers. In choosing the title, I wanted to reference such a collector, and many historical examples came to mind (Peggy Guggenheim, Isabella Stewart Gardner, Gertrude Stein). Ultimately, I settled on Mara. Especially in the context of the Vila, we as a nation have lost decades of untapped potential due to our communist past. Mara could have been born seventy years ago as someone’s grandma or yesterday as my friend’s niece; she stands for past, present, and future. I am looking for Mara, and with this event, I invited a circle that has the sensitivity and curiosity to become that person. It’s a timeless name for timeless aspiration: to be able to contribute to art history.

Mara is the visionary Albanian collector I haven’t met yet.

What is your view and maybe advice on how to be a successful part of the art world today?

Identifying and sustaining talent is itself a creative act. Supporting art isn’t only about owning objects; there is honourable work behind building a good collection. I fully believe collectors can be co-authors of art history, and Albania is ready for its own generation. The role of the collector is something that is not often spoken about; some people want to distance themselves from the financial element of art, but it is time to talk about it!

What are your plans for the future?

I aim to keep developing, testing, and delivering new ways of curation and circulation, and see how I can position my career as a curator/dealer in a city like London. As for Albania, I plan on returning regularly to grow the market ecosystem through an educational lens. For example, I plan to host events where gallerists and seasoned collectors from abroad share their experience, and where new collectors feel comfortable learning. It’s important for the social and critical dimension of collecting to be part of the culture from the start.

Participating Artists: Ada Bond (UK), Ben Grosse-Johannboecke (GER, UK), Blerta Hashani (KSV), Edyta Olszewska (POL), Elis Feka (ALB), Ermir Zhinipotoku (KSV), Franklin Collins (UK), Freddie Bannister (UK), Genc Kadriu (KSV), Genti Korini (ALB), Idir Koka (ALB), Kaddy Saho (GER), Keith Farquhar (UK), Kentaro Okumura (JAP / UK), Leonard Qylafi (ALB), Łukasz Surowiec (POL), Lumturie Krasniqi (KSV), Mary Pye (UK), Meriton Bexheti (GER), Mila Rae Sarabhai (JAP / IND), Nensi Dojaka (ALB), Patrycja Piętka (POL), Renid Tosuni (ALB), Valdrin Thaqi (KSV), Zeni Alia (ALB)

Curated by: Lisja Tërshana and Sofian Khrais

Design and Identity: Amaya Crichton

Catalogue Assistance: Anja Stroka

Khrais–Tërshana – www.khraistershana.com