Her artistic practice is grounded in personal experiences and intimate relationships, through which she explores and reflects broader social realities. For Karina, photography functions as a practice of trust and presence.

How would you describe your photographic language?

The subjects appearing most frequently in my photographs are people I know intimately and with whom I share meaningful connections. Beyond portraiture, I photograph still lifes that I encounter in my everyday life. A recurring motif in my work is the full table—an endless collection that holds particular significance. For me, the table symbolizes presence, friendship, shared moments, and conversation; it is a metaphor for sharing itself. What repeatedly appears in my work is not incidental—it actively shapes my visual language.

What do you want to preserve with your images?

It’s not so much about preservation in the sense of keeping things intact, but rather about observing and reading back the image and the situations unfolding within it. Rather than a static effort to preserve the world around me, I am fascinated by youth, ageing, and the transitions between life phases. For a long time, I didn’t even realise that this was what I was observing and what had fascinated me from the very beginning.

How do you decide whether to use colour or black-and-white film?

It depends on my mood. I began my practice with black-and-white photography, and I maintain a particular relationship with it. The choice between black and white and colour ultimately depends on the situation and available light. However, in recent work, I find myself gravitating toward black and white more frequently.

Who are the people you photograph? Mostly friends, or also strangers?

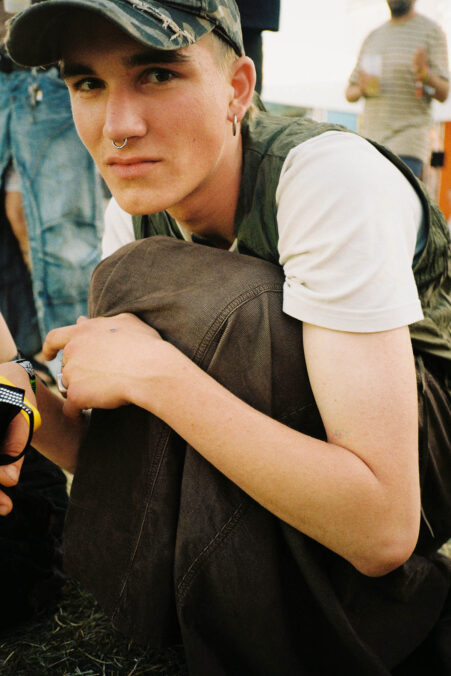

I mostly photograph my close friends and the communities I’ve been part of for years. When I photograph close friends, I feel most at ease. There is no stress, only comfort and openness. When I photograph someone I don’t know, it usually happens at concerts, festivals, or subcultural events. In those settings, taking photos feels natural because we already share something — a moment, a vibe, or a common interest.

There was a period when you appeared in your own photos through mirror self-portraits. Was that a more conceptual decision, or something that happened spontaneously?

The period during which I was taking self-portraits was, for me, a journey of self-discovery. It was a very vivid time for me when I moved to Prague and left my friends and community behind. Instead of photographing friends, I started taking self-portraits and asked myself: “Where am I, and to whom do I belong?” I felt lost. Photography at that time really helped me to situate myself in time and space. On some days, I took around twenty self-portraits. Looking back, I realise it was a really intense period for me.

Is there a particular project that has been especially formative for you so far?

It’s definitely the project Utopia that marked the beginning of my photographic journey. In 2018, I started photographing a building where my friends were living together. The space fostered a sense of communal living, and the former office rooms were illegally occupied as residential areas. This period helped me a lot in defining my visual language. It was there that my first portraits emerged. This project has shaped my work up to the present day.

Do you need more calm or chaos?

I’ve been thinking about a lot in the past few months. I see myself as someone who carries a lot of chaos and noise and, at the same time, as someone who can bring silence and calm. In my photography, I feel these two polarities very strongly, because the life I live and the things I photograph are full of movement, unpredictability, and energy – basically, chaos. And at the same time, there are moments when everything slows down, and space opens up for quiet situations. For a long time, I set these two sides against each other, which brought a lot of confusion and tension. In the past few months, I’ve realised that it’s not about separating or analysing them. They are simply part of me. I’ve realised that I need both and that my work only works when I can hold these extremes together.

What have you been thinking about a lot lately?

I’ve been thinking a lot about creation, photography, and how to articulate thoughts through my work. I believe that over the past two years, I have undergone a big revision of my practice, a period of deep reflection. As I’m currently pursuing my PhD at the Academy of Fine Arts, travelling a lot, and focusing on my artistic research, which deals with psychological resilience and the kind of resilience that emerges through human relationships and communities, this period feels very alive and inspiring.

How did you celebrate Halloween this year?

This year, I spent Halloween sitting on the floor surrounded by approximately 6,000 small contact prints from my entire archive, putting together a zine for my upcoming exhibition.

What projects are you currently working on?

On November 25th, a one-day exhibition titled KILL YOUR DARLINGS took place at KLEMENSOVA 9 in Bratislava, focusing on the themes of archives, friendships, community, and interpersonal relationships. The exhibition’s title stood in a paradoxical relationship to the project’s content. It came from a cliché in the creative industry: “remove what you love the most.” In this project, however, the act of “killing” remained purely linguistic rather than literal. Instead, it drew attention to how much we fear losing what is important to us while also revealing how deeply relationships, memories, and objects shape us. This exhibition was particularly special to me because, for the first time, I stepped beyond the medium of photography and worked in a video-performance format together with my close friends, whom I had been photographing systematically for many years. The project also featured a new limited-edition benefit zine.

Karina Golisova – www.instagram.com/karinagolisova/