In your work, the high heel appears recurrently, sometimes as a found object (readymade), sometimes rendered in silicone, or woven from silver thread. What does this motif represent for you, and how does it function conceptually?

I have a compulsive obsession with feet and everything around them. I’ve collected thousands of images of shoes and feet. I keep on taking pictures of others and of myself, too. I also save screenshots of feet in movies or anything online and collect them. I like to stand in them, to walk in them, and the way they hold me. Every time I see a pair of shoes lying on the ground, I imagine an invisible body standing on top of them, as if the object retained agency or memory. I consider myself an animist, and that impulse—treating things as active rather than inert—tends to place agency in objects.

This interest extends into walking as a practice. A few years ago, I began a project based on walking through Barcelona, the city where I was born and where I now reside. Each walk would trace a path that “wrote” words in the air, like an invisible Hansel and Gretel. As if walking the words would make them have a place in this world, manifest them. For me, walking is a form of resistance: in a moment when everything is commodified and it can feel as if the only legitimate time is time spent producing, choosing to move slowly, to drift, and to occupy the streets becomes necessary to me. I’m interested in thinking about art through a non-productivist logic, where the work doesn’t resolve into a final object but remains in a constant state of transition. I feel grounded in understanding art as an ecosystem, where artistic production operates through transformation and affect, rather than representation and consumption.

Tic-tac-tacón.

I return to high heels because they are a condensed technology of desire. I also work with the motif linguistically: I call them High Heels, and I play with the word by changing the order of its letters or substituting one letter for another, sometimes just for fun, so it can hold two meanings simultaneously. I find that friction between them interesting. For example, “high heals” sounds like high heels, but it also suggests a high capacity for healing—altas curas. As if the line that separates the opposites became blurred. Whether through pronunciation, spelling, or etymology, I’m drawn to words that can mean two things at once. I remember a piece I made in high school where I played with the word “fig,” which in Spanish is higo, and which—funnily enough—sounds like “ego” in English. Looking back across my work, I’m realizing that this keeps happening: I’m often drawn to the tension and ambiguity of duality.

Blurry city lines.

You completed a Master’s degree in Computational Arts at Goldsmiths, University of London. How do you define Computational Arts, and in what ways has this shaped your practice? Before this, you studied photography. How does this background continue to influence your work?

I might begin with a brief personal context. I never met my grandfather, but he was a magician, and I grew up attentive to how illusion works: an audience can believe in “pure magic” while knowing it is a trick. I’m drawn to that tension—one foot in magic, one foot in realness—because contradiction opens breaks through which new meaning appears, as if we had to invent new categories when something resists classification.

I pursued the MA at Goldsmiths because I needed robotics and coding skills to animate my devices —small contraptions, almost like magic tricks. Much of my work is mechanized: hidden motors, strings, gears, and concealed systems set objects in motion and, in doing so, “animate” them. Animate comes from anima (breath/soul), but it also simply means movement—like animation in film. The mechanisms are hidden, yet you can often hear or intuit them—an echo that reminds you of the im/possibility of magic. This is where my core question sits: if something moves, is it alive? I’m interested in how the boundary between the living and the inert becomes unstable— machines as dead and alive at once, like Schrödinger’s cat. As Barad writes: “If lightning animates the boundary between life and death… does it not sometimes seem to plunge into one and sometimes into the other side of the division?”

Before this, I studied Visual Arts at Camberwell, where the influence of my tutor Duncan Wooldridge especially pushed me to push the limits of image-making. Since then, my practice has focused on the investigation of the physical conditions through which images are formed and perceived: light, optics, photons, and the material conditions of measurement. Curiosity about light and particles led me to quantum physics, especially the double-slit experiment and Karen Barad’s quantum-feminist reading of it: measurement (such as taking a picture) is not a passive act of revealing what is already there, but an active configuration that helps produce what can be known and seen and what is left apart. Barad’s ideas about apparatuses, agential cuts, and entanglement have stayed with me, and they connect directly to my interest in illusion: what appears “given” or “default” depends on specific techniques, mechanisms, and arrangements that make certain forms of visibility feel self-evident. Visibility is structured, not accidental: what is present is mediated by absence, and what is seen never exhausts what remains unseen. For Barad, every act of seeing involves selection and exclusion.

Fashion is a persistent presence in your work. How do you understand your relationship to fashion—as a system of representation, a material culture, or a critical framework?

I believe that making ´clothes´ is my way of drawing bodies without doing it due to their anthropomorphic shape. They appear in my work as humanoid activation devices. They are not reminiscences of a way of dressing/covering/grooming the body but a way of performing it. In other words, clothes, in my work, are not a representation of the body but a performativity of it. Representation is very static and feels too rigid to me, but performing relates to activation, fluidity, and change. I believe all the disciplines are deeply entangled. As I mentioned earlier, I find it challenging to draw differentiation lines, as if I were not deciding which characteristics to select or value, to draw differentiation lines, and consequently define disciplines. Things aren’t inherently different in the sense of “classification”. I don’t think anything exists as such as a “one”; I believe reality is a seething mass of entangled probabilities. So I wouldn’t think of fashion and art as having a relationship as if they were two separate entities: they are intrinsically interconnected. And the same happens with politics, religion, literature, and so on…. Being intrinsically interconnected or entangled is a concept coined by quantum mechanics, referring to the lack of independent and self-contained existence; existence is not an individual affair. Rather, unities (such as disciplines) emerge through and as part of their entangled relating.

Your practice also contains kinetic sculptures as well as paper, fine threads, textiles, prints on silver paper, and silicone molds. How do you approach materiality, and what criteria lead your selection of materials?

It might sound super cheesy, but I allow the materials to talk to me and guide me. Many times, I end up doing things that rationally I would have never thought of doing, but when in the studio, where magic happens, I let the materials talk and guide. It sometimes feels like an archaeological work, where I am not really making something but digging and finding something that was already there. I just had to manipulate everything around it to find its final/original shape.

The materials I use are quite varied, but I primarily work with translucent latex, resins, wax, fabric, and pictures. I began knitting silver thread as an allegory for the fabric reality is made of. In quantum physics—particularly in string theory—reality is sometimes imagined as being constituted by vibrating filaments. Everything around us, even the air and the interplanetary vacuum, can be imagined as a weave of intertwined threads. That’s why, when I wanted to evoke a quantum body, I chose woven silver thread. After a while, I started to use latex and resin because of their almost transparent appearance. Sometimes, when an object is fully made of resin, it feels like it is made of light (photons) instead of matter (particles). To me, they are like little light containers, and they

embody that uncertainty.

I would describe your practice between the intimate and the technological, the handcrafted and the machine-made. How do you balance this tension?

I love having one foot on each side of any differentiation line. I feel like when you can not categorize something, new breaches of meaning open up, as I said before. So I’m happy that you mentioned it, as I also feel like my work is always in between the magic and the trick, the alive and the dead, the technological and the intimate, and I like to always be in between.

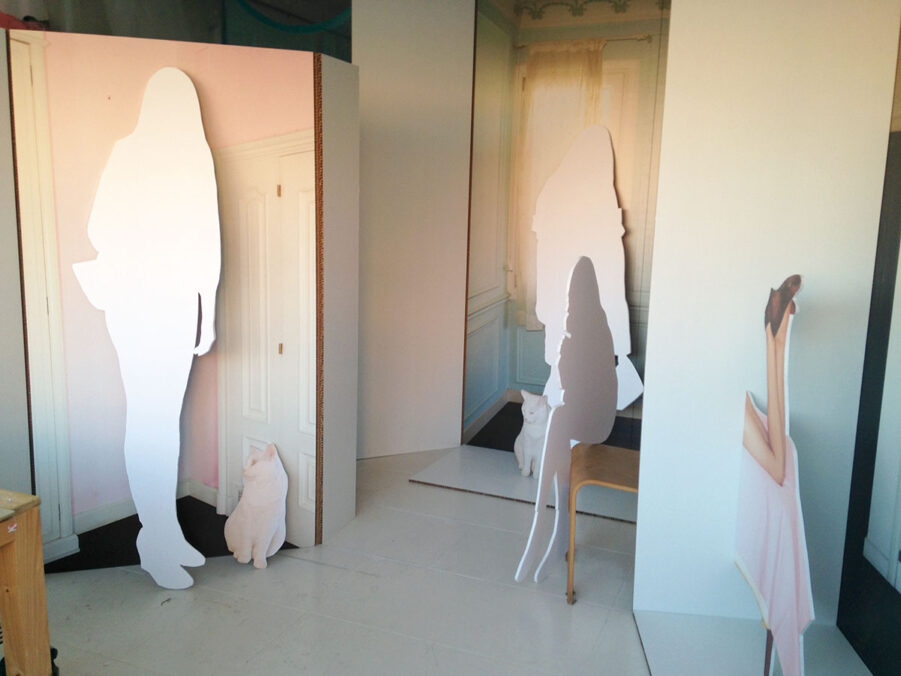

You recently produced artwork in the form of window displays for the fashion brand Gimaguas in Barcelona and Madrid. Is it your first time doing work in the commercial context? The paper silhouettes of female figures and their pets suggest narrative and identity. Can you share with us who those women are we see there?

I see the intervention I did at the Gimaguas shop windows as a life-sized game. I wanted it to be super playful, and it was! The project drew on the games I used to play as a heterobasic femme kid, especially “playing house” with dolls.

In the Madrid store, there were two separate windows, and each one staged a room. You could see both rooms at once, much like looking into a miniature dollhouse. The girls in the images are some of my friends. I also love that, from the back, the cut-outs become pure outline: because the cardboard is white, you only perceive the contour. I’m especially fond of the word silhouette, even the way it sounds.

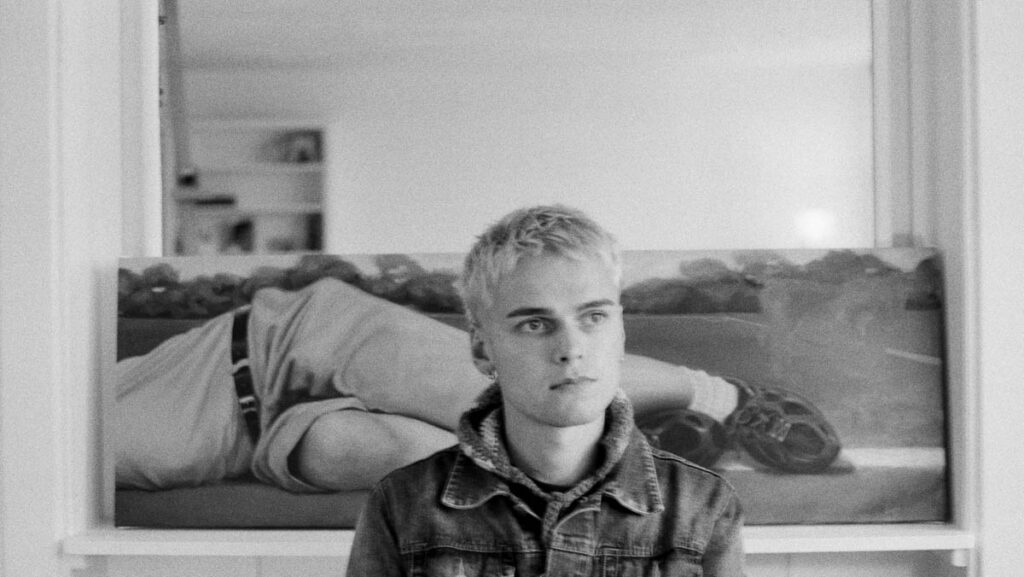

Julia Creuheras – www.julia-creuheras.webflow.io, www.instagram.com/juliacreuheras

Julia Creuheras (1995) is a Barcelona-based artist working across kinetic sculptures that remind us of nostalgic and dusty relics that treasure uncertainty. Despite the fact that she shapes heavy materials such as metal or wood, her pieces are subtle and fragile; almost ethereal. Originally, the machines she made started as a way for her to embody basic concepts of Quantum Mechanics. Through them, she aimed to dismantle the agents of production of knowledge that entangle us with the nature of reality to draw closer to a concept of truth. Similarly to how puppets are pulled by visible strings, the visible mechanisms in her pieces function as active dismantlers of the forces that move the world of the mundane and the ordinary. This body of work, which was heavily marked by a certain obsession for answering questions about the texture of reality, has gradually mutated into a current body of work that is more focused on the question per se or, perhaps, in what motivates the question itself.