Blending classical painting techniques with digital processes, Kanti creates layered, surrealist compositions that challenge dominant narratives and explore themes of resilience, memory, and transformation. Her work offers a visual language that bridges ancestral knowledge with contemporary discourse, inviting viewers to reflect, unlearn, and imagine more just and sustainable futures.

Your work explores themes of identity, femininity, and cultural memory. How does your background in Uzbekistan shape this exploration?

My work moves between the local and the global, but it is always filtered through the lens of women’s lives. As a woman artist, I believe that incorporating these embodied perspectives into contemporary discourse is not only necessary. It is fundamental to rethink how we tell stories, how we construct memory, and how we envision the future. I live and work in Tashkent, and my environment directly shapes the questions I ask through my art. Uzbekistan is not just where I’m from; it’s a place I’m in constant dialogue with. It holds complexity: tradition and transformation, silence and resilience, restriction and beauty. I don’t simplify it. I work from it. My interest in identity, femininity, and cultural memory doesn’t come from theory; it comes from observation and lived experience. In Uzbekistan, much is expressed without words. Women carry strength through gesture, ritual, textiles, and presence. I pay attention to those subtle codes because they often say the most. My work doesn’t reject where I am. It examines it. It asks what is hidden, what is preserved, and what needs to be reimagined. I’m interested in how women navigate systems, how they endure, and how they create space for themselves despite the weight of history and society. Tashkent gives me context, tension, and clarity. It challenges me and grounds me at the same time. I use that energy to build something that speaks beyond one place, but always starts from where I stand.

Which aspects of the female experience are you particularly drawn to in your practice?

I’m not drawn to a single, clean version of the female experience, because such a version doesn’t exist. I am not looking for stories of perfection. I am drawn to complexity, to the contradictions, the broken lineages, the invisible labor that defines much of women’s existence. Through my work, I want to show layers: tenderness and brutality, endurance and fragility, anger and beauty.

Are there personal memories that keep resurfacing in your work?

Certain memories stay beneath the surface of my work. They are not stories I want to retell, but emotional landscapes I keep walking through. But memory doesn’t appear as a direct reference; it appears as a structure. It’s the architecture underneath everything, unseen, but determining the shape of what’s possible. They insist on being present through the way I handle material, space, and absence. I’m less interested in illustrating what happened and more drawn to exploring how memory reorganizes itself over time. How it blurs, distorts, and reconfigures into something living. In that sense, memory is not a subject for me; it’s a collaborator. It presses against the work, demands space, and refuses to be reduced to simple narratives.

How do you choose the medium that best fits a particular theme or idea? What role does visual, spoken, or written language play in your work?

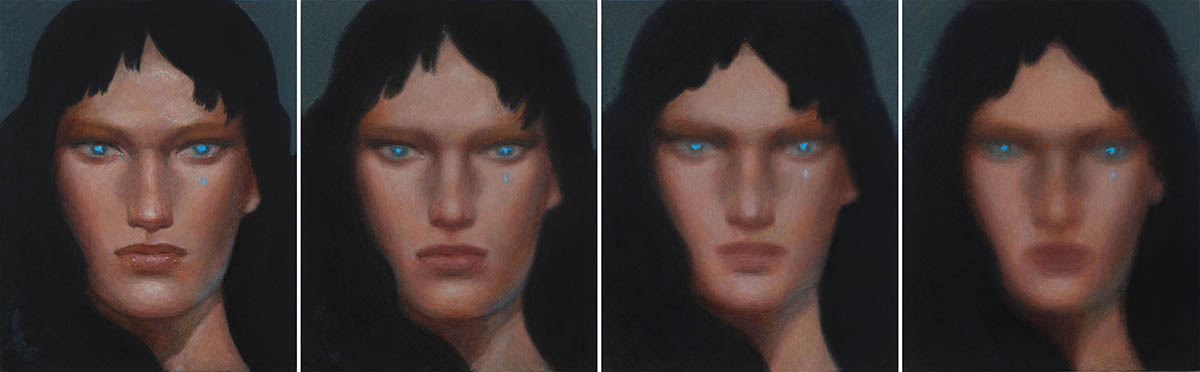

The medium isn’t separate from the idea; it grows with it, through the body. I don’t choose materials for aesthetic reasons. I follow what the work demands. What begins as an emotional pressure or a fragment of memory slowly finds its form through the process. For the last two years, I’ve been building a mixed media technique that’s become central to how I work. Each painting begins with at least forty layers—layer after layer of material, texture, concealment, and disruption. I like to think about the surface as living skin. I scrape it back, bury things inside it, and return to it again and again. The physical labor of layering becomes part of the meaning. It’s slow, meditative, it takes time, and the time becomes part of the work. When I shift into video/ video installation, the visual still leads, but sound becomes necessary. It allows the space to breathe. The moving image extends the painting into time. It lets me bring the body into landscapes of memory and resistance. I want the viewer to feel surrounded—not just to observe, but to be physically affected. There is no distance between concept and material. I stay close to what I make. The work comes from the body, and it returns to the body. Always!

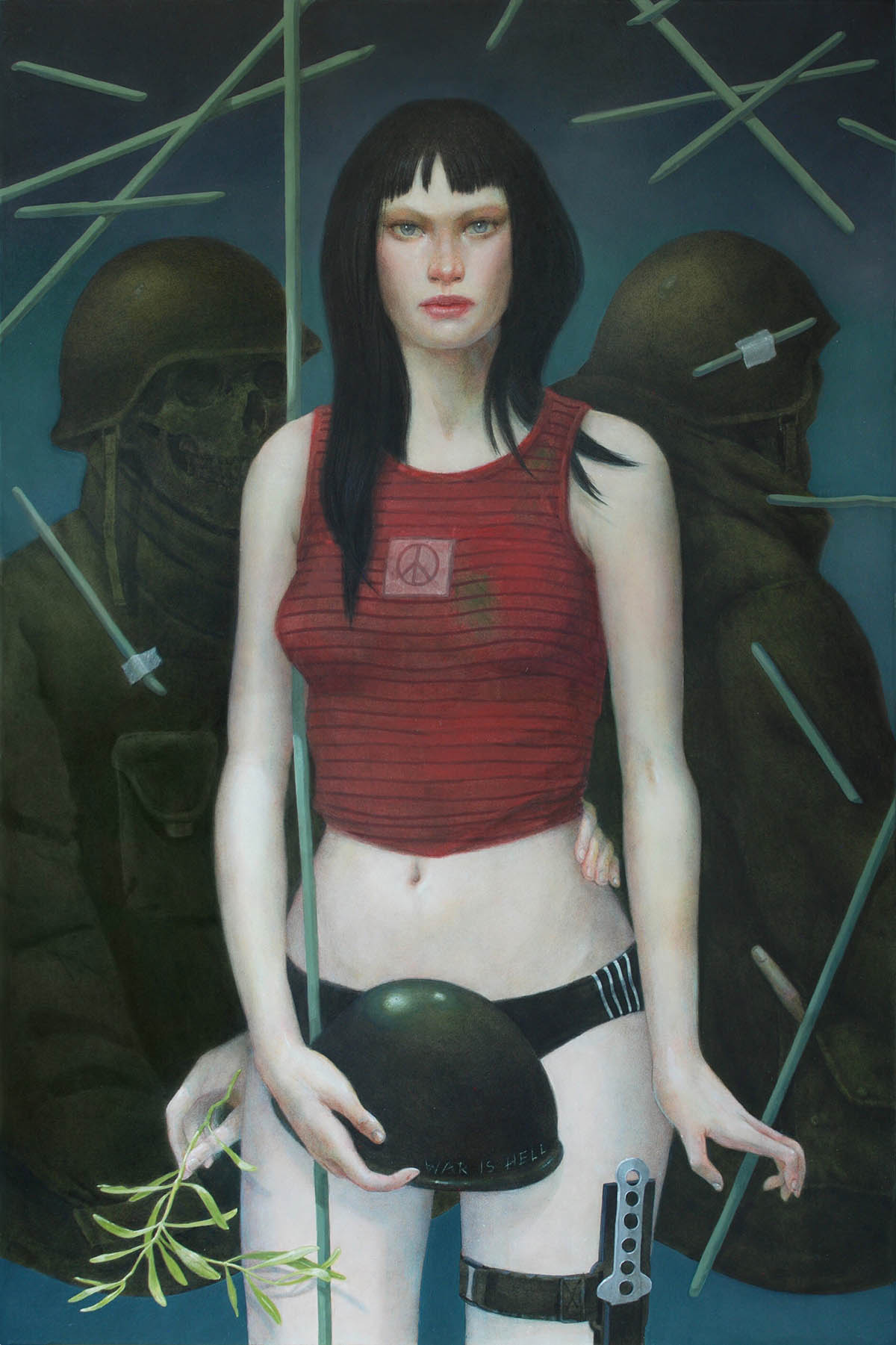

„Daughters of two Rives“ from the project „Echos of Resilience “ 2025

What does your creative process look like? Do you work more intuitively or conceptually?

It’s never just one way. Some works begin with a sharp clarity; a wound, a question, something I have to hold in my hands. Other times, I just start moving — pencil to surface, camera to gesture — not knowing where it will end. I don’t do sketches. I don’t map things out. That kind of control flattens what I’m trying to reach. But there is always a dance between precision and chaos. A moment of control, followed by a plunge into something wild and unknowable. I move between those states constantly, one breath structured, the next completely unplanned. That tension is not just part of the process; it is the process. It’s what keeps the work alive. Control gives the piece its bones — a line, a decision, a shape that knows what it’s doing. But chaos brings the blood. It stains, it spills, it interrupts. I need both. Too much structure, and the work becomes obedient, too polished to feel. Too much disorder, and it loses its voice, it forgets what it came to say.

So I listen. I wait. I follow the material, but I also push it. There are moments where I step back and choose — here, this needs weight, that needs silence. And then I step in again, letting the hand move before the mind catches up. That’s where something real happens — not just made, but revealed. It’s like breathing in two directions: one inward, deliberate; the other outward, free. The space between the two is where the truth catches fire. And I stay there as long as I can.

I really like your work „Opa Qiz Ona“. Could you tell me more about it?

Thank you! “Opa Qiz Ona” is a raw ritual carved from silence, where wounds become form, and pain is given a shape it’s so often denied. It confronts what is almost unspeakable: the loneliness, the mental fragmentation, the isolation that women and girls face after sexualized violence. In many places, especially where I come from, a woman who has been raped is left alone, not only without support, but with blame placed directly on her shoulders. As if the violence was her doing. As if silence is the only acceptable response. This work is not about telling a clean story. It’s about stepping into the fog, into the nervous system, into the psychic collapse that happens when trauma is forced to live inside without release. I wanted to enter that mental space: the distortion, the dissociation, the ache, and make it visible. Not polished, not digestible. It’s an act of resistance against the way society prefers to bury these women twice. First through the violence, and then again through silence. “Opa Qiz Ona” is also a mourning and a scream. It holds the echoes of sisters, daughters, mothers, all the ones who were never allowed to speak. Through this work, I ask them to speak with me.

In recent years, I’ve noticed that Uzbekistan is increasingly being promoted as a travel destination. Could you share a bit about the country with me?

I’m glad that now more people are discovering Uzbekistan. There is a growing interest in its Uzbek art and culture, both inside the country and internationally, and it feels like something that has been needed for a long time. For me, I love Uzbekistan for its everyday beauty: the geometry of architecture, the way tea is poured with care, how fabric is dyed, the quiet ritual of meals shared under mulberry trees, the sound of traditional instruments echoing through courtyards. I often weave these sounds into my video works; they carry memory, spirit, resistance. I believe everyone should visit Central Asia at least once in their life. Uzbekistan lives between timelines, past and future, tradition and modern. The landscapes shift — from desert silence to mountain breath to ancient cities humming with stories — but it’s the emotional landscape that stays with me. The people carry a quiet strength, layered with resilience. To understand Uzbekistan is to slow down and pay attention to what is said, and what is not. To the glances, the gestures, the silences between words.

What’s the art scene like in terms of galleries or off-spaces?

The art scene in Uzbekistan is growing, but is still finding its form. In terms of galleries and off- spaces, there are a few state-run museums that focus primarily on traditional or academic art, and some institutions focusing on contemporary art. Experimental work is slowly gaining more visibility, but the infrastructure to support it, like independent galleries, residency programs, or alternative exhibition spaces, is still quite limited. It’s not a fully developed scene yet, more like a constellation of individual efforts, sometimes disconnected, but full of energy. There’s a hunger for dialogue, for experimentation, and for new forms of expression. What’s missing is more infrastructure and long-term support, but the desire to create and connect is very much alive.

Where are you currently based?

I’m based in Tashkent, a place that lives in my bones, but the work travels where it needs to go. Borders don’t contain it. Last year, I took part in Rroma Lepanto, a collateral exhibition of the 60th Venice Biennale. It wasn’t just an exhibition, it was a ritual of return. The invitation came through the curatorial team of the Kai Dikhas Foundation, whose work in amplifying Rroma voices resonates deeply with my own. The project was realized in collaboration with ERIAC, The Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma, and the European Cultural Centre — each one part of this wider act of cultural repair. To stand in that space, in Venice, with other Romani artists, was to reclaim something that had long been spoken about us, but never with us.

My work lives in the silences, in the spaces where women such as Roma and unnamed others have been misread, overlooked, romanticized, or erased. Rroma Lepanto made space for those voices to be heard, not as myth or metaphor, but as truth. For me, it was about standing inside the narrative, holding the thread, and saying: we are here, and we have always been.

What are the questions that currently drive you the most — artistically, politically, or personally?

The questions that drive me now are not theoretical. What does it mean for a woman to hold space without justification, without softening herself for legibility or acceptance? In cultures where feminism is stigmatized, how can art become a language of resistance, care, and reclamation? What visual forms can carry the complexity of the female experience without collapsing it into stereotype, victimhood, or purity?

How do I hold the complexity of being a woman, tender, angry, sacred, and exhausted, without simplifying it for the comfort of others?

What does healing look like when systems continue to wound? How do I protect non-Western cultural memory without reducing it to heritage or romanticism? Can art decolonize without being consumed by the very structures it critiques? What does it mean to create from the margins — not for validation, but for visibility on our terms? Can art serve as a form of care and protection for communities who are constantly asked to justify their existence? How do I stay connected to my ancestral languages, gestures, and rhythms — and still speak to a global audience without translation flattening me?

And finally, what do you wish for your future?

I don’t chase visibility for its own sake. What I want is depth. I want to continue making work that refuses to be easy work that disturbs, heals, and remembers. I want to remain connected to what is honest, even when it’s painful. I want to stay close to the rawness that drives me, and never let it be softened by expectation or approval. I wish to grow without losing the edges. To collaborate deeply, across disciplines, across borders, with those who carry the same urgency. I want my work to reach the places where it’s most needed, especially where voices have been ignored or erased. As well as I also want to protect the inner space where art is still ritual, still rebellion, still sacred.

Dariya Kanti – www.instagram.com/dariyakanti/