Your work is currently on view as part of the Curated by program at Galeria Dawid Radziszewski in Vienna; the group exhibition “Durée” is curated by Reilly Davidson.I listened to the short podcast introduction for the show, and thought I should reach out.

I am always happy when people who have followed my work for a while get to actually see it in person. When artists come to New York and do shows, I feel the same way; it’s always exciting to see art in real life.

Your collaboration with curator Reilly Davidson seems pivotal: how did that shape the exhibition? Reilly and I are in constant conversation. We exchange images, texts, and ideas daily. She has a clear vision and a strong aesthetic sense. She found in me someone working towards a similar conceptual and visual language. The other artists in the show were chosen for the same reason—she curates around a vision. That’s what makes her an incredible curator and writer.

In an older interview of yours, you said, “A painting is incapable of telling time. It’s a static image.” I was struck by that. Could you expand on what you meant by painting being static, even as time moves around it?

I think about that line a lot. For me, it comes down to how painting wrestles with temporality. I had this idea of a painting functioning like a clock or borrowing the form of a clock, but disrupting that form so that it fails to tell time. And in doing so, it calls attention to painting’s own nature: it’s static, it’s fixed. You’re always aware of its immobility. Yet at the same time, a painting participates in this huge conversation across centuries.

I often think of Malevich’s Red Square—a work from around 1915, originally titled “Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions.” It was a sort of parody of Millet’s The Gleaners. Malevich was asking: What can painting really do for peasant women? A red square doesn’t change its condition any more than Millet’s sentimental realism. That’s where the question of aesthetics as representation comes in; images are not the thing itself; they are signs.

That’s the ground I work on—painting as a conversation around meaning, aesthetics, and signs. Images are not the thing itself; they’re signs for the thing. So painting sets the stage for semiotics, Baudrillard’s theories, and all of that.

Your work seems very engaged with theory like Wittgenstein’s “aspect-dawning” and phenomenology, and the experience of perception (viewing).

I’m very interested in how we experience a painting. Pure experience is often discussed in art history, but I approach it skeptically. I want to explore what lies between pure experience and the signifier. My work investigates that tension, how we recognize, interpret, and relate to visual forms.

That makes sense. You also have a background in photography. How does that influence your approach to painting?

My early photography was extremely abstract and painterly. I experimented a lot in the darkroom. Photography taught me to question the “truth” of an image. I was never a documentary photographer; I was always trying to expand the medium conceptually, which naturally led me to painting, where I felt that there was more room for experimentation and dialogue with (art) history.

Speaking of history, your representation of the female body is fascinating. It’s symbolic rather than portraiture, correct?

Yes. I’m skeptical of figurative art as a direct expression of the self. My figures are disembodied and symbolic; they could be anyone, or no one. Ideally, they might even be genderless. The goal is to explore the relationship between the viewer and the image, rather than documenting a specific person I know or don’t know.

So there’s a grounding in recognizability, but also abstraction.

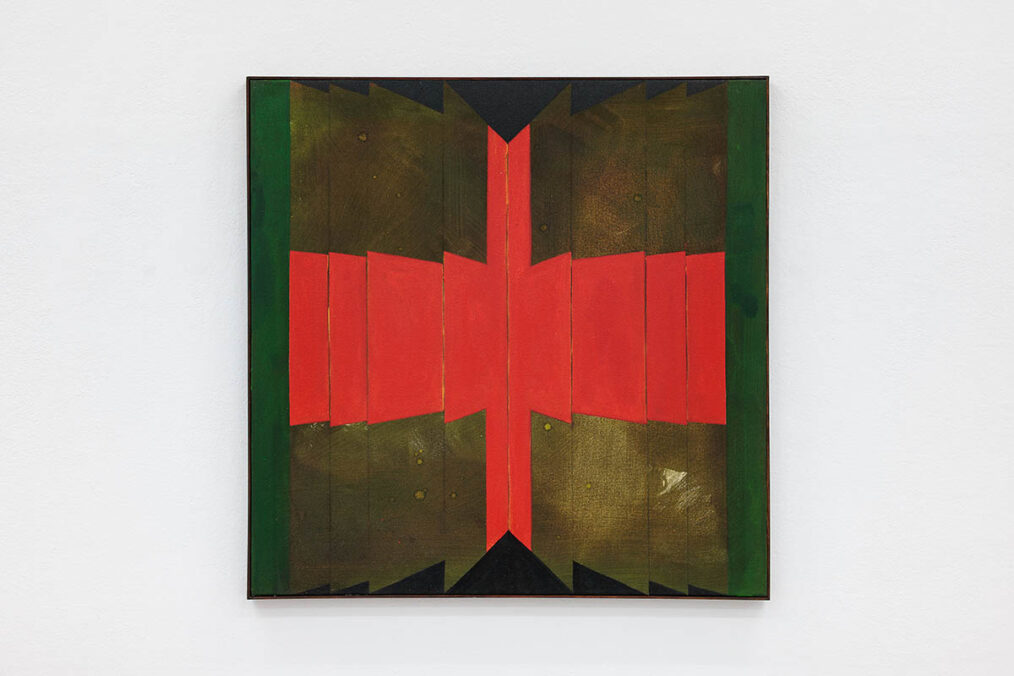

I’m skeptical of pure abstraction, too. If I made a Malevich-style painting today, people might just see historical references rather than experiencing something directly. My work situates itself in a postmodern landscape, where recognition and abstraction interplay.

What would you say, how does the viewer’s interaction change in the age of screens and Instagram?

It’s impossible to ignore that the internet changes everything. People see your work online before they see it in real life. Platforms like Instagram shape the perception of art. Ignoring it would be unwise. When I started, I tried making pure monochromes and quickly realized that no one would engage with them in 2025—they belonged to the past. I think that communicating through these systems is a way to speak to the present.

And your work is consciously tuned to the present moment?

Color, structure, and composition in my work are all calibrated to engage a 2025 viewer. There’s no point in making work that doesn’t speak to the world we live in.

My practice channels intensity and “too muchness”- into painting, it’s where I can let it all out.

Your solo exhibition “Bastard Rhyme” at Matthew Brown Gallery in New York is also a pure take on the architectural aspect of the exhibition space. The exhibition is running until October 18. 2025.

I think a lot about the conditions under which a painting is viewed. I am aware of the point when the work goes out into the world, it’s no longer controlled. My show at Matthew Brown features double-sided paintings, arranged architecturally so they communicate with each other, mimicking the internal relationships within the frames themselves.

What about writing? Do you engage with text as part of your practice?

Very much. I write a lot about what I’m reading, seeing, and thinking—mostly for myself, except for a small book I did on the occasion of the exhibition in Capri Space in Düsseldorf. But text has a significant place in my work. Dialogue with writers, like Riley, or writing for my own reflection, is essential for processing ideas.

Do you think this writing will matter for art history in the future?

Yes, language contextualizes visual work. Artists like Robert Ryman or Ad Reinhardt are better understood through text. Without it, many ideas would remain inaccessible. Writing provides a foothold for future viewers to understand today’s work.

And originality: how do you see it in your practice versus AI-generated works that are more and more appealing, especially in painting?

I don’t think I invented modernism; I’m not creating in a vacuum. But my work is inherently individual; it cannot be reproduced exactly. AI has its own aesthetic logic, and I see it as a mirror of our world rather than a tool for making my paintings. It’s fascinating but fundamentally different from human creation.

You mentioned that you have your archive of shapes and symbols you collect. How does that work?

I collect images on my computer, often from books or scanned archives like the New York City Picture Library, things like that. Mostly, I’m interested in images at the threshold of recognizability: children learning language, invented language systems, gestures, and cave paintings. Occasionally, I print and collage these images into new works. It’s about chaos meeting recognizability.

You are based in New York, but you were in Vienna last winter. How did you like the city? I had a show in Germany not so long before I visited Vienna. I was a proper tourist in Vienna; I was literally checking all the boxes. Opera, many museums, all that stuff. Vienna’s culture and tradition in the arts really blew me away. I remember my visit to the Kunsthistorische Museum; I thought I could stay there for days, full of inspiration.

Last question, do you have any guilty pleasures, non-art-related?

Honestly, yes. Puzzle games on my phone. I also love to dance. That’s it. That’s my break from the studio.

CURRENTLY ON VIEW:

Solo exhibition: Bastard Rhyme by Olivia van Kuiken

Exhibition duration: September 05- October 18, 2025

Venue: Gallery Matthew Brown, 390 Broadway, New York

Group exhibition: Durée, curated by Reilly Davidson

Exhibition duration: September 05- October 04, 2025

Venue: Gallery Dawid Radziszewski, Schleifmühlgasse 1A, 1040 Vienna

Olivia van Kuiken – www.oliviavankuiken.com, www.instagram.com/livankuiken

Olivia van Kuiken (b. 1997 in Chicago, Illinois) is a New York-based artist. She received a BFA in Studio Art at Cooper Union, New York, 2019. Solo Exhibitions include “Losing looking leaving”, Caprii, Düsseldorf (2024); “Beil Lieb”, Château Shatto, Los Angeles (2024); “Make me Mulch!”, Chapter NY, New York (2023); “She clock, me clock, we clock”, King’s Leap, New York (2022), “Bastard Rhyme”, Matthew Brown, New York (2025).