How did your collaboration begin, and how did it develop into an almost ten-year-long partnership?

We met at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki in 2013, when Océane was on exchange. From the start, the encounter was charged and energetic. There was an immediate curiosity, not only toward one another, but toward how the other perceived the world and interacted with environments. We began by supporting and assisting each other’s early individual practices.

The collaboration grew organically out of everyday exchanges. Through constant conversation and the circulation of materials and ideas, a shared perception slowly formed. Over time, this became a kind of artistic dialect: shaped by gestures, movements, and repeated ways of paying attention to environments, objects, and affects.

A turning point came in 2016 during a two-month residency at Mustarinda (Hyrynsalmi, Finland), where we began working literally with four hands. We developed a material-poetic approach grounded in bodily experiences of space and time, mixing romantic irony with attentiveness to transformation and metamorphosis. Residencies and shared experiences of place became central ways of anchoring the collaboration and feeding the studio work. Eventually, the collaboration was titled Touristes Tristes, named after our first solo show in 2017. Working together opened a space of freedom: a place to experiment, learn from one another, share skills, and pursue ideas we might not have dared to explore alone. After a couple of years, we realized that the collaborative mode had become like an abstract sculptural-image-making machine or a being with its own logic, tempo, and artistic language.

Alongside Touristes Tristes, our individual practices have continued to evolve and feed the collaboration. In the last few years, we have focused more on our individual practices, and Touristes Tristes has been lingering and brewing ideas in the background. Now we think of the three practices as moving together, sometimes closely intertwined, sometimes at a distance. We feel this elasticity is key to the continuation of our collaboration.

What do your regular studio days look like?

There is very little regularity in our studio days, apart from a constant dance with entropy! Because our practices move across techniques and materials, clear studio routines are tricky to maintain; some kind of sense of rhythm is important.

The studio is not separate from everyday life; for us, it is lived life. Working days involve a lot of handling and moving materials, reorganizing space, eating together, or dozing off on a couch. These mundane acts coexist with moments of contemplation, play, and intense production focus. We’re both quite instinctual in our approach, following affective hunches rather than clearly defined topics. In this way, the studio functions also as a kind of magic sphere: a place where attention shifts, time stretches, and spaces open.

Much of the daily process takes the form of ongoing spatial sketching and speculation. dylan often moves between assembling objects and sitting nervously on the couch with a notebook, circling ideas through drawing and writing. Océane’s process is more attuned to subtle currents, zoning into unintentionality, sensing when something is ready to shift or when it needs to remain still.

Both our collaboration and our studio days oscillate between movement and stasis: flowing and getting stuck, slowness and busyness. This rhythm, echoed in our exhibition title The Slow Business of Going (2020), has become central to how we work. We usually work on multiple pieces at once, allowing loose systems to emerge rather than enforcing a single direction. At the end of the day, there is often a quiet moment of looking at accidental forms or strange assemblages left behind. Slowly, through this accumulation of acts and observations, a body of work comes into being.

Can you tell us about your latest exhibition you did together, ‚Swallowed Rooms’—how did the title come about? Your titles are generally very poetic; how do you develop them, and what is the process behind them?

‚Swallowed Rooms‘ was presented in 2025 at SIC in Helsinki, and it followed Water under the Fridge, a duo exhibition we showed in 2024 at In extenso in Clermont-Ferrand. Both exhibitions were accompanied by Katia Porro, a curator and writer based in France, who has worked individually with each of us over the years and closely followed our collaboration.

Glassbox, Paris, Photo: dylan ray arnold

Although the exhibition brought together our individual practices, it was strongly framed by a shared life and studio. Over the years, working, living, and thinking alongside each other has created a specific metabolism of materials, references, and poetic perceptions. Ideas, objects, and affects circulate between us, are digested differently, and re-emerge in distinct forms. The exhibition worked as a constellation rather than a unified narrative: two practices operating autonomously but within the same atmospheric and conceptual climate.

The works brought lived environments into dialogue with corporeal and mental spaces. Textiles, drawers, and fruit pits appear through shifts in scale and repetition, becoming carriers of emotion, memory, and thought. We were interested in a kind of psychic infrastructure made of daily systems that mirror bodily and emotional processes.

The title ‚Swallowed Rooms‘ refers to experiences and spaces that consume and fold into themselves. Mirrors swallow other rooms, objects withdraw or collapse inward, and familiar domestic arrangements become interiorized. It also points to the metabolic nature of our practices: chewing, absorbing, transforming, and re-articulating materials, spaces, habits, and everyday loops.

More generally, our titles function as virtual extensions of the work. Because we often work with mental diagrams or compositions that can feel quite hermetic, titles become a way to open the work sideways. It can also be a way to smuggle in some personal anecdotes into the work. We collect phrases a bit in the same way as other quotidian things. They can come from slips of language: misheard conversations, song lyrics, or chapter titles of a found book. We write extensive lists and develop titles not only on the kind of meanings they connotate, but moreover their sound; how they vibrate with the work. Titles allow language to metabolize experience in the same way our practices do.

Tell us about the solo projects and exhibitions you did in 2025?

Our solo projects can be understood as continuations of the duo exhibitions. They carry forward shared concerns around metabolism of quotidian life, lived spaces, and slow transformation. Installing work into space is a crucial part of how we think, so each solo exhibition emerged through a dialogue with its specific context and the vibe of the space.

In her solo show Fall, presented at Titanik in Turku, Finland, Océane explored how two central aspects of her life, her permaculture practice and her lived experience of chronic autoimmune illness, intertwine with her sculptural work. Both directly shape her relation to the world and how she works with and through materials and space. Moving between sculpture and installation, the works combined a heterogeneous range of materials, including ceramics, textiles, plaster casts, glass, paper, wood, and organic matter from her garden. Everything was presented on the floor, and as the title suggests, the works connected to a sense of corporeal gravity and an emotional groundedness. With a careful spatial composition, Océane wanted to create a space for a slow attention to the haptic; textures and materialities that relate to organic bodies and their transformations.

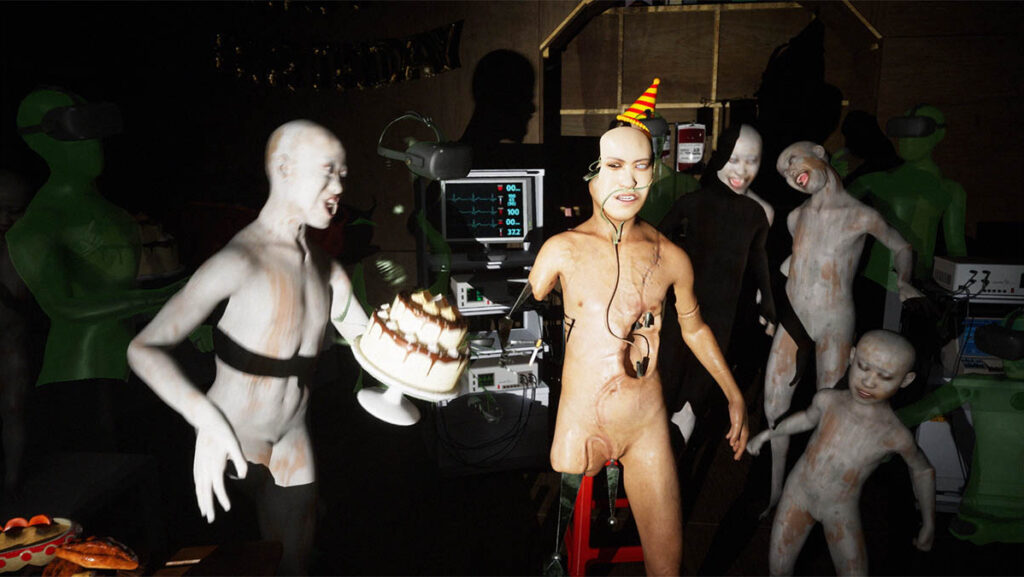

dylan’s solo exhibition ‚Aging etc. feelings ‚ at Sculptor gallery in Helsinki, took the form of a spatially composed sculptural installation built from everyday materials. The works related to experiences of ageing, vitality, and decay as they register both in the body and in lived environments. Drawing on affective memories of the 1990s home, the exhibition lingered in forms and linty objects charged with desire, attachment, and discomfort. Reworked textiles, fragments of furniture, and parts of household appliances performed scenes of micro-drama, expressing both first-person experience and the layered life of the objects themselves. The exhibition could be read as a kind of hospice for materials where care, exhaustion, and continuity coexist.

Your works are very complex, detailed, and well thought through. How does the composition emerge—is there space for intuition, or is everything planned and sketched from the beginning? Composition for us is not fixed from the outset. It emerges through an ongoing interplay between structure and intuition. We both tend to work with bodies of work simultaneously, so many pieces share the same pool of materials, motifs, and gestures, often echoing one another. Scale, repetition, and material sensitivity become ways of establishing relationships rather than executing a plan.

A key structural working tool in this process is metaphor, understood as a way of perceiving relationships and patterns across different phenomena. For us, the metaphoric is (counterintuitively?) a very material process, grounded in a corporeal experience of how we orient ourselves in the world. For example, an idea of the way things are organized freely on a fridge door can work as a metaphor for both spatial and affective relations. Metaphors are important in the way we understand both our practices as well as specific exhibition projects, like, for example, metabolism in ‚Swallowed Rooms‘.

Details tend to nest and accumulate, much like the way everyday life gathers around us. Assemblage is therefore not only a formal strategy but also a way of thinking about being: we understand ourselves as assemblages shaped through continuous interaction with our environments. This extends to how works relate to one another in space. We are interested in the idea of living systems with permeable boundaries: how works can both hold themselves and remain open, stable yet capable of leaking and affecting one another.

Our individual approaches differ a bit within this shared framework. dylan’s process often involves a nervously ongoing play of building and deconstructing, a form of world-making that searches for a latent, case-by-case logic of things. Océane’s process usually starts with poetic and corporeal attraction, but often requires more planning of different phases, especially when techniques demand it.

Overall, the process resembles a strange loop (like all living systems), moving between instinct, repetition, metaphor, play, and exact refinement. For both of u,s the intuition is guided by an obscure sense of precision. The work remains grounded in the interaction with our daily surroundings and in an interest in the polymorphous space where gestures, relationships, and environments continue to transform.

You work with a wide range of materials. How do you decide which materials to use, and what are the biggest influences on that process?

Our choices grow primarily out of everyday life. Alongside traditional sculptural materials like wood, clay, or steel, we work with collected and repurposed textiles, furniture, objects of daily use, as well as more specific or singular items encountered by chance. Elements also circulate across projects and time: we reuse, transform, and recombine parts from previous works.

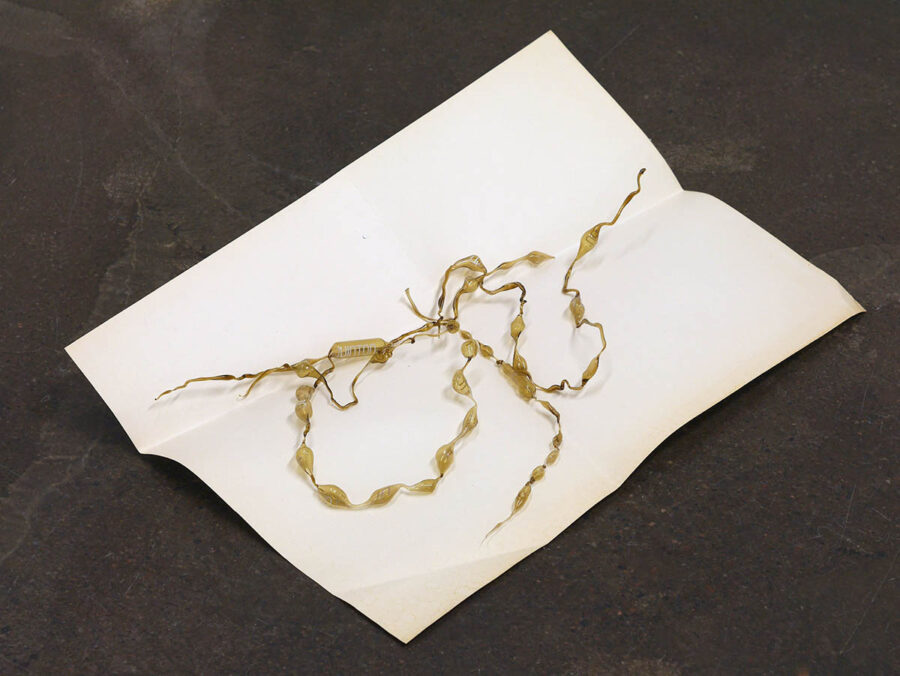

We like to develop quite an intimate relationship with the things we work with. Materials are tested through touch, proximity, and spatial arrangement, rather than selected solely based on their common meaning. Sometimes the choices stem from personal attachments, as materials carry subtle affective and relational weight. Océanes fruit pits, for example, function as an affective storage: corporeal memories of holding something in the mouth, of duration and care. Alongside these resonances, physical and visual qualities like texture, color, or fragility are equally important.

We are particularly drawn to materials that belong to lived environments, things that are still present yet perhaps becoming obsolete (or exhausted, like Liz Magor has described the objects she works with). These can be seemingly insignificant fragments of everyday infrastructure, objects worn by repetition, or materials layered with the sculpting-pressures of time.

What should we all be reading in 2026, and what did you read in 2025?

We hope everyone in 2026 will be reading love letters from their friends! And more poetry.

We are quite random readers, reading contemporary Finnish and French authors. When in need of some energy for working, we often return to Amy Sillman’s collection of essays on art, Faux Pas (2020) for its perceptive, generous, and playful but articulated thinking, and to Anne Carson’s collection of poems Wrong Norma (2024) for the sheer pleasure of following language as it unfolds and does things. In 2025, reading was also shaped by grief, following a significant loss in our family. Vinciane Despret’s Our Grateful Dead: Stories of Those Left Behind offered a way of thinking about how relationships with the dead can continue and transform. From a more academic angle, The Materiality of Mourning: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives (edited by Zahra Newby and Ruth Toulson), helped articulate how objects, bodies, and matter participate in processes of loss and remembrance.

In these crazy times, we’ve found that allowing grief to be part of life can open a sense of continuity, care, and humility: an awareness of being alive as something shared.

Océane Bruel – www.oceanebruel.com, www.instagram.com/oceanebruel

dylan ray arnold – www.dylanrayarnold.com, www.instagram.com/dylanrayarnold

Océane Bruel is from Montpellier in the South of France, and studied Fine Arts in Paris, Helsinki, and Lyon, where she obtained an MFA from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

dylan ray arnold is Finnish-Swiss and holds an MFA from the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki and a Master’s degree in Sociology from the University of Helsinki.