How many people currently work at the foundation, and what kinds of roles do they have?

The person in charge of everything happening in the foundation and with the 6-Day Play is Rita Nitsch, Hermann’s wife. She’s also likely the most knowledgeable about Nitsch himself, so if, for instance, a museum is looking for details about an action from 1982, she’s the go-to person. Our responsibilities range from overseeing the strategic direction and organizing exhibitions to managing the overall coordination of projects. Our Managing Director, Gudrun Marecek, primarily oversees collector and institutional relations. She also coordinates our marketing activities and manages collaborations with external partners. Another key team member, Martha Schildorfer, is responsible for project coordination.

In such a small team, roles naturally blur — everyone wears multiple hats and contributes where needed. That’s also what makes it exciting and flexible.

How do you see your role within the foundation? What are your main tasks?

My main focus is working with external galleries: The Pace Gallery from New York, Gallery RX from Paris, and so on, and I am coordinating exhibitions and sales with them. I also reach out to museums and curators to explore potential collaborations, finding shared projects we can work on together. That’s a big part of what I do. In addition to that, I handle the less glamorous but essential aspects of financial oversight. I ensure we have enough funding to operate, work on financial planning. Since I have a business background, this naturally falls under my scope. I’m also involved in initiating new projects, thinking about where the foundation is headed over the next 10 years. It’s essential to constantly evolve our strategy. In small teams like ours, everyone contributes creatively, and I think that kind of collaboration helps move the foundation forward.

The foundation has changed since Nitsch passed away. How has that affected your work?

Yes, absolutely. Since Nitsch passed away, we’ve transitioned from working with a living artist to managing his estate. That shift changes everything—our focus, our responsibilities, and even the kinds of questions we ask. We’re now considering what Nitsch’s legacy should look like and how his work will be represented going forward.

Are rituals still important in the foundation?

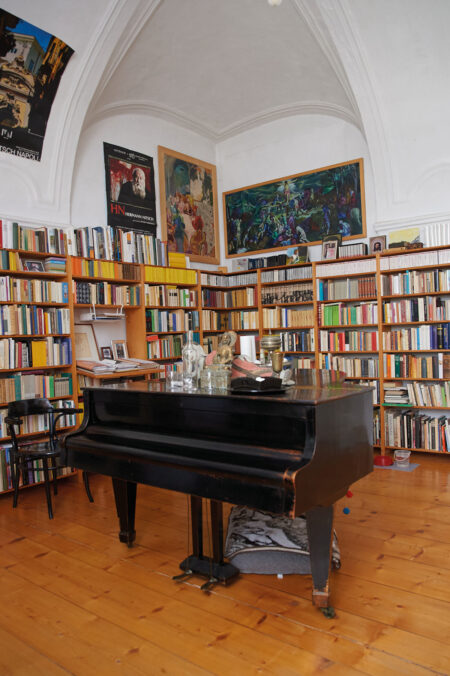

Rituals are still important. Nitsch was a very communal person, and you can see that reflected in his art. We’re currently at Schloss Prinzendorf, and apart from the staff in Vienna, there are always four or five people working here, handling everything from gardening to restoration. He lived these rituals daily. For example, every day there’s a communal lunch, where everyone working here or visiting sits together. Nitsch always sat at the same place and engaged with everyone—“What are you doing today?”—that kind of thing. Food was important to him, and after 5 PM, he loved to enjoy a few glasses of wine, which comes from his own vineyard. He also had personal rituals—sitting in his office listening to loud music, often Wagner or his own compositions, and working intensely for a few hours. He wrote a lot—philosophical texts, musical scores, and so on. His painting cycles, the painting action, were also ritualized, even if done by him alone or with just an assistant.

How does Nitsch’s work engage with contemporary sociopolitical issues?

The Nitsch Foundation was founded in 2009, while Nitsch was still very active. From the beginning, the foundation aimed to support and preserve his work. That’s still what we do today—making his work accessible and acting as a hub in Vienna for anyone interested in his art. Nitsch grew up during WWII—he experienced bombings in Vienna firsthand—so themes of war, crisis, and trauma deeply influenced him. In light of today’s global instability, I think his work still resonates.

We also host exhibitions of other artists—those influenced by Nitsch or connected to him personally. In that way, we remain part of Austria’s contemporary art discourse. We’re not limited to established names; we also support young artists who reflect on similar themes or build on Nitsch’s legacy.

Can you tell us more about Nitsch’s international influence?

Nitsch was truly cosmopolitan. Early in his career, he couldn’t perform freely in Austria—he was even jailed for his work. So he sought audiences abroad. He had performances in the U.S., Italy, France, and many other countries. His legacy is global. For example, the Centre Pompidou in Paris recently made a large acquisition of his work. They even included Nitsch in their permanent collection. He performed in Paris as early as the 1970s. Known artists such as Paul Mcarthy and Jonathan Meese have been impacted by him. Marina Abramović, for example, once performed in one of his actions—while her work is very much her own, the influence is certainly there.

How did religion and ritual influence Nitsch’s performances?

Religion played a significant role in his work, though not in the traditional sense. As a young man, he wanted to be a church painter and trained as a graphic designer. But what inspired him were ancient rituals and religious ceremonies. He was fascinated by the drama of life and death, like the sacrificial rituals found in ancient texts, where an animal is killed to feed the community. That tension between death and life, destruction and renewal, is at the heart of his work. His performances weren’t spontaneous—they were choreographed in detail, scored, and rehearsed. He wanted to create a kind of total theater, a spiritual experience. Though not religious himself, he believed in the cosmos and was deeply spiritual.

What can you tell us about this place, Prinzendorf, and its connection to Nitsch?

Prinzendorf meant a lot to Nitsch – he specifically wanted to live and work here. His „field theater“ performances were designed with this landscape in mind, and while they’ve been performed elsewhere, this place holds special significance. He loved the vineyards, the wildlife, seasonal changes. He would spend hours just observing nature—watching chickens, the vines, the sky. He’d often say that all of life’s drama could be found just by watching animals interact. It gave him a deep sense of cosmic connection.

How would you describe the atmosphere during the 6-Day Play? Could you share some details?

It is structured so that we perform the last three days of it, each one lasting a full 24 hours. During those three days, there’s an ongoing celebration, almost like a communal festival. There are performances throughout each day and night, all based on scores that Nitsch wrote. Visitors can come and go, enjoy the performances, explore the surroundings, drink wine, and eat together. It’s a total sensory experience—visual, auditory, even gustatory. The performance includes a full orchestra—more than 100 musicians—playing throughout the 3 days. Around 60 to 80 actors participate, coming from Austria, Germany, Finland, Belgium… It’s a very international group.

How do food and drink play a role in the performance?

Food and drink are integral to the 6-Day Play. Nitsch even specified what should be served each day. He cared deeply about food, especially traditional Austrian cuisine and dishes from cultures that use every part of the animal, like in French or Chinese cuisine. He would always ask people he just met, “What’s your favorite food?”—it was his way of connecting. As Nitsch didn’t believe in waste, all animals used in the performances are supposed to be consumed afterwards, even though we are not allowed to do that due to regulatory restrictions. The meals reflect his values, and the communal dining is part of the ritual. We expect 400–500 visitors, plus orchestra members, actors, and staff. Feeding and hosting everyone over three days is a massive undertaking, and yes, it involves a lot of wine—all of which is made right here at the castle’s vineyard.

What about the ethical questions surrounding the use of blood and animal carcasses?

Nitsch wanted to confront people with the reality of death. The animals used in his performances come from sources where they would otherwise end up in supermarkets. So the ethical question starts with: Why do we consume meat at all? For many people, seeing a dead animal in a performance is the first time they truly confront what that means. Nitsch believed that using the whole animal in an artistic and communal context could be a meaningful and respectful act.

Why did Nitsch write such extensive instructions for the 6-Day Play?

The final version of the 6-Day Play is over 1,000 pages long. Nitsch began developing the concept in the 1950s, and it became the focus of his life’s work. The first full performance took place in 1998. Between then and 2020, he expanded and revised it into a second edition, which is now published.

He wrote it in such detail because he wanted it to live on after him — and it will. Without his instructions, I don’t think we’d feel confident carrying it out.

What inspired him to create something so monumental?

It was the culmination of his life—his thoughts, experiences, and conversations. He was deeply influenced by music (he loved Wagner), religion, philosophy, and his writings. He even published a book called “Das Sein”(„Being“) on his philosophical views. So the Six-Day Play brings all of that together—painting, music, performance, and a focus on all five senses. It’s an attempt to reach the essence of human existence.

The Orgy Mystery Theater

June 7–9, 2025 Schloss Prinzendorf,

Performance of the last 3 Days of the 6-Day Play

Address and contact:

Schloss Prinzendorf

Schloss Straße 1, 2185 Prinzendorf an der Zaya, Austria

www.nitsch.org/schloss-prinzendorf/

The 6-Day Play by Hermann Nitsch, first performed at Schloss Prinzendorf in 1998, is considered the most monumental work of his Orgies Mysteries Theater. It is a continuous six-day and six-night performance engaging all the senses of participants and spectators. Music, painting, ritual acts, sacrificial symbols, and sacred elements merge into an intense experience that explores existential themes such as life, death, ecstasy, and transcendence. The meticulously planned performance, involving hundreds of participants, reflects Nitsch’s pursuit of a universal, spiritually charged artwork that provides space for reflection and catharsis.

Hermann Nitsch (1938–2022) was one of the most influential and controversial artists of postwar art and a central figure in Viennese Actionism. His works, characterized by radical physicality and ritual intensity, dealt with existential themes such as life, death, and spirituality. Through his Orgies Mysteries Theater and his oeuvre as a whole, Nitsch created a unique total work of art that viewed art as a cathartic experience. Nitsch’s work exemplifies provocation and a break from traditional art forms. His pieces are part of major collections and museums worldwide, underscoring his outstanding position in contemporary art. www.nitsch.org

Founded in 2009, the Nitsch Foundation aims to promote the significant position of Hermann Nitsch as an artist and to preserve his legacy, the Orgies Mysteries Theater. Its mission includes raising awareness of the conceptual foundation of his work, publishing editions and publications, organizing actions and performance events, curating and realizing exhibitions, fulfilling archival and documentation tasks, and expanding the catalogue raisonné. www.nitsch-foundation.com, www.instagram.com/nitschfoundation/