What role have informal meeting places played in Viennese culture? And how does the city deal with this topic?

Kilian Hanappi: The most cliché but iconic, informal place in Vienna is probably the Kaffeehaus. Whenever I’m somewhere else—especially now, living in Berlin—I miss it. Spending an entire afternoon with just one espresso and a book creates a zen-like environment with little financial investment. Cafés here tend to feel more commercial. Some even have stickers on the plates saying “no laptops,” especially on weekends, to ensure people don’t linger without ordering more. Informal spaces generally have this ephemeral, almost magical quality. They appear, disappear, and often leave little or no trace at all. I remember one from my school days in the 14th district. There was a secret inner courtyard that some students from nearby schools called “California.” It was just a five-minute walk, so during our lunch break, we’d sneak off to chill there. One day, I asked a classmate if I could join him, and suddenly, I was in this hidden garden—shaded, breezy, and perfect for rolling and passing joints. It felt like a pocket of freedom. But, of course, that didn’t last. After a few months, the people living in the upper floors started noticing the smell and called the police. The spot got busted, and we had to move on. That’s how “New California” was discovered—another garden, even closer and cozier. I still wonder what happened to that place. And if it still exists. It reminded me a lot of how students might have discovered Zwidemu—it probably followed very similar logic.

How long did the research for the exhibition “Zwidemu: Between Party and Process” take?

Paul Buschnegg: The research for the exhibition was based on a workshop at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, led by senior scientists Korinna Lindinger and Florian Bettel – and took in its core about half a year. Together with my classmate Eddie van Gemmern, I wanted to discover how and why the space evolved and when it was appropriated as a youth cultural hotspot in the first place. We talked to lots of older people, including police officers who had been monitoring the space for ages – but nobody knew when and why it happened. Some thought of Zwidemu as something that the pandemic had created. But we knew from memory that the term „Zwidemu“ was much older – so we interviewed lots of friends and friends of friends who had spent a lot of time there as teenagers. In the end, we found the earliest evidence of Zwidemu on Facebook, on several Postings from early 2010. Facebook, ironically, maybe is The oldest social media we have, and works as a surprisingly rich archive of social movements and things that were happening back in the early 2000s, so I wouldn’t recommend anyone to delete their Facebook accounts—Other “archives” like Netlog, StudiVZ or Myspace are either gone – and with them, maybe even earlier evidence of Zwidemu.

Were there any surprises during the research, and what impressed you the most?

Paul Buschnegg: At first, we were surprised about the fact that Vienna had this very political Movement called the Burggartenbewegung in 1979/1980. Back then, sitting and lying on the lawn was forbidden, and young folks did it to reclaim space in this – back then – very dusty and grey Vienna. So, after we read a lot about the movement and spoke to some participants, we were even more surprised to find out that around 2010, something similar had happened. Back then, different groups revolted against restrictions in public space in the inner city, organised “Sit-Ins” on the lawns of “Heldenplatz” and in the “MuseumsQuartier”, where Vienna’s flagship projekt banned bring your beer and skateboards. The movements were fueled by a new form of media — social media — and its various tools, such as Events, Groups, and Pages, helped bring people together. It is bewildering to also realize how much from this spirit shifted in the last 15 years to filter bubbles, fake news and radicalisation.

What was important to you when selecting the artists for the exhibition?

Kilian Hanappi: The most important thing was choosing artworks that resonated with each other. We tried to tell a story purely through the dialogue between the pieces, without focusing too much on media, form, or creation time. The more different they were, the better. The artworks should also intertwine with historic texts and objects, forming a coherent whole—ideally without relying on wall texts, which, let’s be honest, most people don’t read anyway. That led to the challenge of realizing that there weren’t many existing artworks directly connected to Zwidemu’s history. So we started thinking about artists from our university—friends and colleagues—whose works could already make sense in the exhibition. In some cases, we slightly adapted existing pieces that had a close conceptual connection to the site “between the museums.” One example is The Naked Square, a project by the artist collective of the same name, which showcases 64 photographs of performances where they built “human sculptures” at various locations in Vienna’s inner city. We asked them to produce another photo at Zwidemu for us. Another is Creature of the Daylight, a filmed performance by Veronika Haller that references Günter Brus’s historic Wiener Spaziergang from 1965—with a wink. These works felt like they belonged or could be gently shaped to fit. Apart from that, we bounced ideas off each other, thought about works we’d seen around Vienna, and created space for artists to produce new pieces. In the end, three of these commissioned works made it into the exhibition.

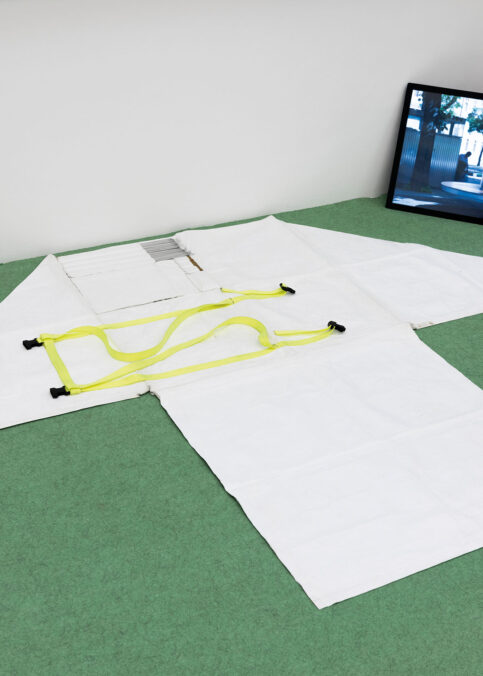

How do you understand the work „Fragments of Home“ by Lilith Ona and Miriam Fee Billisich as a social statement?

Selin Göksu: The artists focus on the subtle ways people—especially those without homes—use public space to create a sense of belonging. They hand-wove a textile and used found objects—discarded materials and bits of trash—to build small pieces of furniture. These gestures, tied to domestic comfort, speak of resilience and the ways people reshape their surroundings to meet everyday needs.

Tell us about the architecture in Zwidemu.

Paul Buschnegg: The interesting thing about the Zwidemu space is that it’s a Neo-Baroque garden. Baroque architecture is known for expressing power relations; it is highly militaristic and absolutist, designed for surveillance and the demonstration of control. But at Zwidemu, people tend to use these „absolutist structures” to hide. The big topiary bushes make surveillance quite challenging; thus, the historical garden does not fall under the jurisdiction of the City of Vienna but under the jurisdiction of the Federal Gardens. Therefore, the Viennese Police are technically not responsible for teenagers lounging on the lawn. Spaces where jurisdictions overlap or are not clearly defined, as exemplified by Zwidemu, seem to be well-suited for appropriation. But when thinking about appropriation, we have to keep in mind that space is not being appropriated just by lazy „leftish“ teenagers, but by various groups. At least since the Pandemic, Zwidemu is not being appropriated just by teenagers but also by right-wing agitators like Identitäre, Covid-deniers, and organized daytime raves with well-hidden party-political overtones.

Is it even possible to protect these spaces in a curatorial way? How? What do you think?

Selin Göksu: Our goal was never to protect or advertise the space itself. Instead, we focused on understanding and showcasing the conditions that allowed this transformation—from a Neo-Baroque garden to a lively meeting point for all sorts of gatherings. By highlighting these shifts, we hope to inspire similar developments rather than preserve one specific place.

What is the role of social media, and how is this presented in the exhibition?

Selin Göksu: Based on many conversations, we suspected the informal use of Zwidemu began around 2010—but traditional sources offered no documentation. Facebook posts, comments, and group discussions helped us reconstruct the timeline and challenged many of our assumptions. In groups like Wiener Wiesn für alle, local politicians clarified responsibilities, while others casually marked the shift from “MQ —> Zwidemu.” To reflect the significance of this material, we placed selected Facebook posts—enlarged and unedited—at the entrance of the exhibition.

Paul Buschnegg: Yes, we have this Facebook feed right at the entrance. That was important because we wanted to show how communication happened in the 2010s—the years we’re focusing on. It was about community and how people were building groups. As I said earlier, back then, social media worked differently. E.g., the Facebook-feature that lets you drop a pin on the map and call it “My Home”, “Zwidemu,” or whatever came up around 2010. That kind of location visualization was key and helped Zwidemu to grow since there was no specific address—just a place in between museums. Social media back then seemed much more social, whereas Instagram today seems more focused on gatekeeping than on connecting.

What was your best night at Zwidemu?

Selin Göksu: There were many, but more than the evenings, I remember those long afternoons—lying on the grass with friends after school, watching the clouds drift by.

Recently, I read that Vienna is planning a “clearly defined space for parties” on the Danube Island. What do you think of this plan? Positive movement or a restriction that could impact party culture? Also, what did your research reveal about this?

Kilian Hanappi: Restrictions are funny things. I wouldn’t say they’re always bad—some can even foster creativity. For example, one limitation we faced while preparing the exhibition was that we weren’t allowed to use the museum’s outer columns to make the show more visible from the outside. At first, we were frustrated. But that limitation led us to the idea of painting the city’s water pipes—which run past the museum entrance—bright pink. The idea was to create this continuous, earthworm-like sculpture, a kind of mascot for the exhibition. In the end, the museum committee rejected it—it would’ve been too complicated to get permission from the city. So, in that case, more freedom would’ve helped. But still, the idea came from a limitation, and I think that’s telling.

Back to Donauinsel: I honestly don’t think it’s ever really been the place for raves. I remember freezing nights, failing to find the right party, running out of gas for the generator, or showing up at the wrong coordinates because someone’s phone died. But maybe that’s also part of the thrill… I don’t know. I think dedicated “party zones” sound okay in theory, but they’re always at risk of being instrumentalized. Party culture should grow naturally. It needs room to breathe and evolve. Formalizing it too much can kill the spirit.

Exhibition: Zwidemu: Between Party and Protest

Curators: Selin Göksu, Kilian Hanappi, Paul Buschnegg

Artists: Lisa Braid, Hanna Besenhard, Ulrich Formann, Veronika Haller, Nike Hartmond & Hansi Wimmer, Julian Lee-Harather, Lena Kuzmich, Lukas Meixner, Medienwerkstatt, Lilith Ona & Miriam Fee Billisich, KLITCLIQUE, Das nackte Quadrat, Dominik Scharfer, Felix Schwentner, Lukja W

Exhibition duration: March 27 – August 17, 2025

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday 10 am–6 pm

More about the exhibition: www.wienmuseum.at

Address and contact:

Wien Museum MUSA

Felderstraße 6–8, 1010 Vienna

www.wienmuseum.at

The exhibition “Zwidemu: Between Party and Protest” sheds light on the various facets of this intriguing place. What is its composition? What role did beer bans, cannabis fairs, and Facebook groups play in its constitution? And what significance does the site have today? The Startgalerie assembles works by young Viennese artists that probe Zwidemu’s history and current state. They encourage reflection on the politics of public space and the role of youth culture in the city.