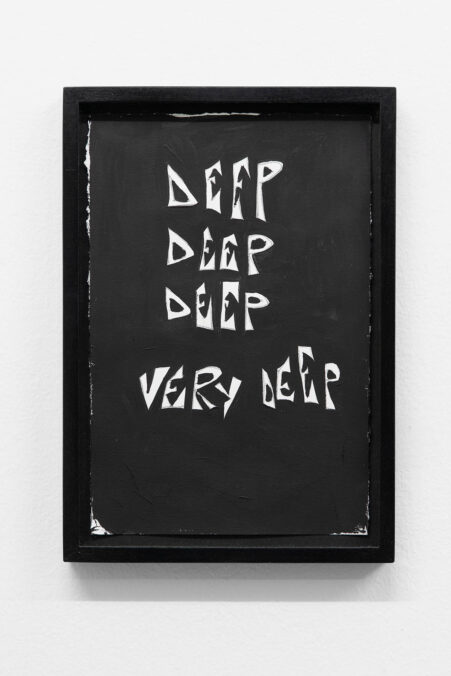

Happy to have you in Vienna! Your solo show “Deep, deep, deep, very deep” just opened at EXILE and will be on view until June 28. Can you tell us more about it? And what does “deep, very deep” mean to you?

It is challenging for me to create happy, gentle, or colorful art in the current world situation. But I always played with “grey” humor, the limits of what we can tolerate, the line between a smile and a feeling of horror. I like to touch liminal spaces and put the visitors in uneasy situations. I want them to feel unsure whether they should smile or cry. Deep, deep, deep, very deep is the title of one of my painting-poems, a sentence that comes from one of my performances, Stories or Rivers, a cabaret about abortion. It can be a message about feelings of depression or arousal, and I like this tension.

There is a special kind of poetry and sentiment running through all your works; they feel significant and honest. How would you describe your sensibility and your process?

As a child, I was oversensitive. I went through a difficult period as a teenager, harassed by other pupils at school for different reasons, which I could only analyze after. Over the years, I managed to rebuild myself around the trauma, and now I may give the impression of being strong or even hard, but I still have this little voice in me asking: Do I speak too much? Will people accept me? Am I annoying, boring? Should I stop speaking?

Behind the carapace, there is still this little person, over-sensitive, this vulnerability I tried to erase for years. It is probably she who is doing the laces in my work that are completed by the stronger character who is writing characters like Strakati, which you can see during the show in the video work on the website of Exile Gallery. I don’t like the word authenticity. I think the concept has become so important that it can mean anything, such as the concept of transparency, but I believe in honesty. And I try to build my relationships and my work from that angle, because I still believe that being honest with yourself and with others is a value we should stand for.

Your practice is very broad, and you’ve created an impressive number of projects. Your work spans sculpture, installation, painting, film, and performance. How did you first start making art, and what has driven you all this time?

I was raised in a theatre, where I was a child actor, playing different roles. This part of my life has been in a state of rejection for quite some time, but as you know, things often come back, despite one’s will. As far as I remember, I always wanted to be an interior architect—maybe because it was my father’s job. The father never recognized me and ignored my existence since before I was even born. I did one year of architecture, but I didn’t like the approach. I felt I wanted to try other things, sound, moving image, and went to a fine art school in Nice, at Villa Arson. Maybe what has driven me all my life is this internal need to fight to be alive and recognized. My mother raised me alone in 1980s France, and I can tell you, she had to fight her whole life. So maybe what keeps me going is also that: the fight to live, and to live according to what you believe in.

I imagine you’re one of those artists who can work anywhere, but where is your studio located at the moment, and what does it look like? Do you carry a notebook around, make voice memos, or have another way of saving ideas so you don’t forget them?

I do not have a real studio, I have a room in my flat. For all these years of being an artist, I didn’t have the money to rent a studio, so I learned to work without one. My conditions led me to be a kind of project person, which was quite a common way to work in my generation. If I allow myself to dream, I would love to have a place to be able to put all my costumes and props, as in a closet, to see them together, maybe also with the sculptures and other pieces. More than a studio as an artist, I dream about a nice storage.

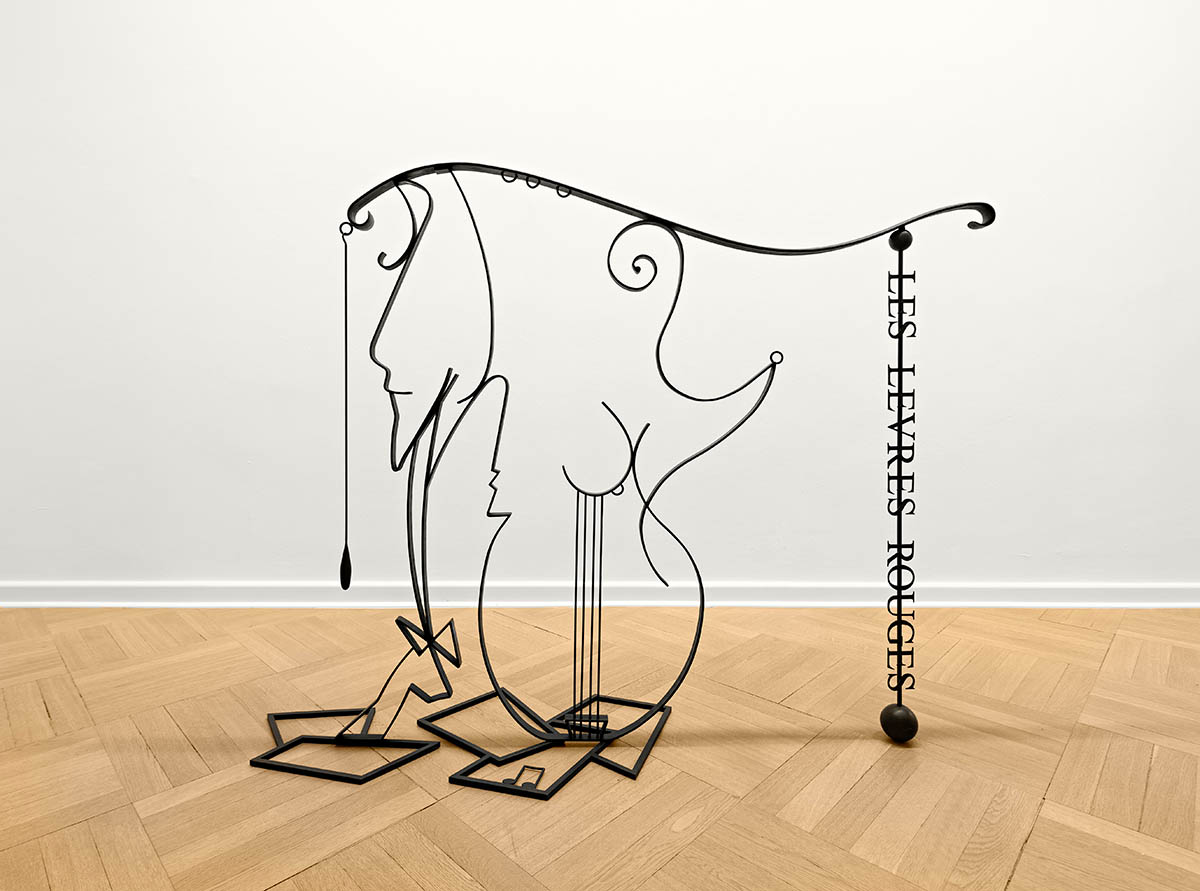

I used to have notebooks, but I don’t anymore. The older I get, the more I keep things in my head. If I need to write something down, I use the notes app on my phone. I also do a lot of voice memos when I’m writing a performance, because I often have melodies in my head for the text. I draw a lot when I am preparing new pieces, especially sculptures. As I don’t have a studio, I sculpt with my pencil, and I love this moment when the piece evolves through the drawings. I usually have between 20 and 100 drawings per show. So it is quite a lot.

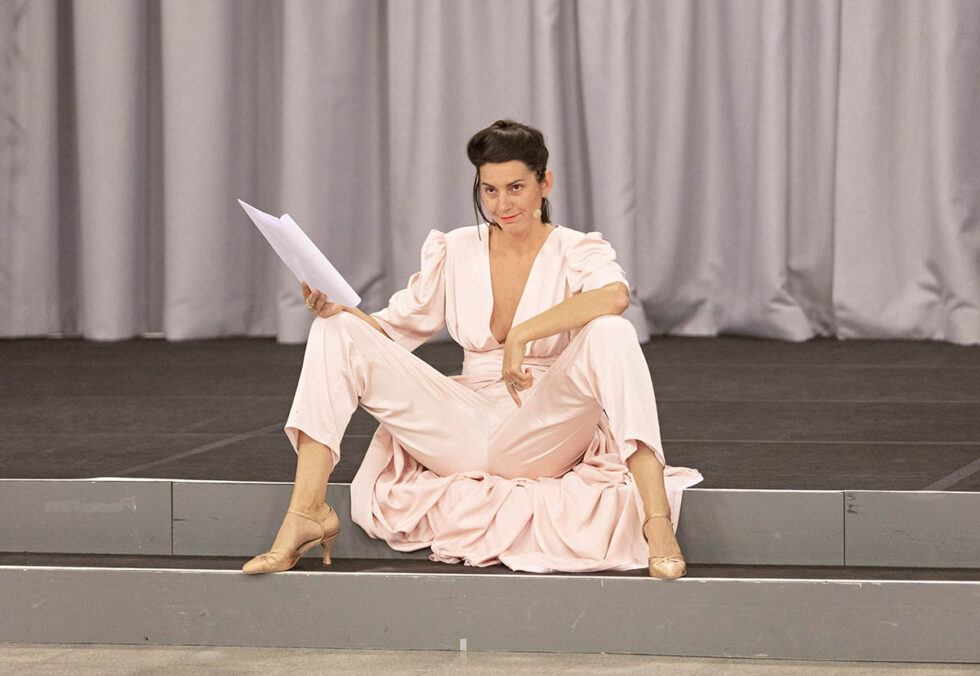

Many of your works feature fictional characters or hybrid entities, like Anna & the Jester. What draws you to character-building, and how do you develop their personalities?

The character who changed my life was the first I embodied, Rose Pantopon. She was a kind of alter ego, and she helped me to develop my practice. Through her, I became able to speak again on stage. She allowed me to mix and exist between my different lives, loves, and hidden stories. She allowed me to become what I am today. Since then, I have had many other characters, the main one is the Jester character, which I created for myself 8 years ago, for a performance in Bologna.

When I am thinking about a character, I have an intuition. I usually begin by drawing their costume, because each of my characters has a specific costume, and then I think about the shoes. These elements are defining the way I will act, the way I will walk, the postures I will take, the mimics, etc. Meanwhile, I am developing their language by watching other people, remembering their small gestures, voices, intonation, and sounds. I never take mimics from fictional characters, but from a real person. And then I compose, and I compose mostly in my head. I often live with them months before the performance or the film, so my husband always says that during those periods, I am away. The last character I created is Jean, who is shown in the exhibition. He is probably the more sleezy, but also the more clownish. But for me so far, he is the more funny to perform, because he has something quite disgusting of an old, now mostly disappeared, male conception, that is quite nice to embody as a woman. Specifically, as we are always asked to be beautiful, sexy or nice.

In several projects, mundane or corporate elements, like banisters, curtains, or elevators, gain a strange autonomy. What attracts you to these banal objects?

I am interested in the contact that the performativity objects can have. You are touching the banister to go up or down, it can be cold or warm, it creates a setting for a situation. You are closing or opening the curtains, passing through them; it is a very dramatic, cinematic moment. The elevator is similarly a fantastic tiny space-time, where you can suddenly be very close to others, and it can be the beginning of any kind of story.

I often work with spaces and objects that are temporarily but intimately and sensitively linked to our bodies, that have a big narrative potential.

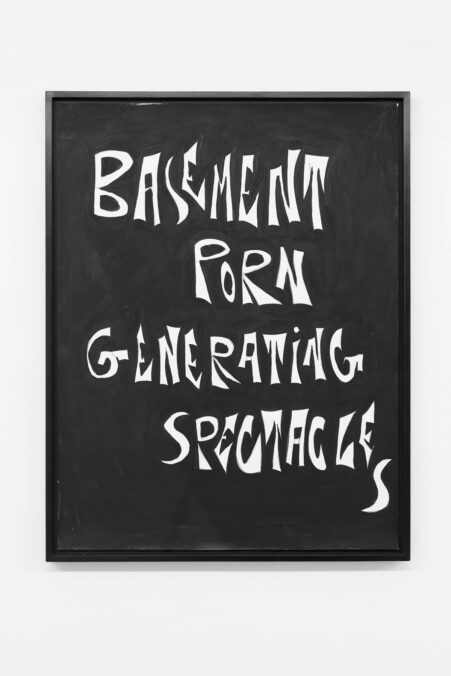

Language, puns, and double meanings are crucial in your titles and scripts. Do you write everything yourself, and how do you shape meaning through text?

Yes, I write everything, but it doesn’t happen overnight. When I finished art school, I was hardly able to write a single line. I have always read a lot, and I’ve always been into spoken word because of my theater past. I was also extremely influenced by Godard in this regard. How voice and text can twist the image, and how to play with editing through that. And I always loved to stretch the meaning of my pieces through their titles. So little by little, the text became a fundamental part of my work, in my performances, in my films with long monologues, in my sculptures that often incorporate words, or letters, and now also in my paintings that are poems. It has something to do with the ability to speak as a character, but in this way to speak for yourself.

What are you reading or watching at the moment?

Now, I am reading The Axe, by Ludvik Vaculik. In the last months, I loved The Doorman by Reinaldo Arenas, Jazz by Toni Morrison, and The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa. For the film side, I started Rodeo, by Lola Quivoron. I fell in love with one of the first Almodovar films: Pepe, Luci, Bob, from 1980. Then the last month’s favorites were Cecile B: Demented by John Waters, The Wharf, the world’s, Next Century by Piotr Szulkin, Babysitter by Sonia Chokri, Suzhou River by Lou Ye, and the fabulous Simone Barbes or Virtue by Marie-Claude Treilhou.

Currently on view in Vienna:

Solo exhibition: Julie Béna – Deep, deep, deep, very deep

Exhibition duration: May 16 – Jun 28, 2025

Location: E X I L E, Elisabethstraße 24, 1010 Vienna

Julie Béna – www.juliebena.com, www.instagram.com/juliebena/

Julie Béna was born in 1982 in Paris, France, and currently lives and works between Prague and Paris. She is a graduate of the Villa Arson, Nice, and attended the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. In 2012–13, she was part of Le Pavillon, the research laboratory of the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. In 2018, she was nominated for the Prix AWARE Women’s Art Prize. Béna took part in a number of residencies, including at Fonderie Darling, Montreal, CA; Futura, Prague, CZ; ISCP, New York, US; Moly Sabata, Sablons, FR, next to others. In 2017, Béna’s first book, It needs to be tender and to be whipped, was published by Montez Press and launched in Paris, New York, and San Francisco. In 2019, her first monograph was published by the Jeu de Paume, Paris, accompanying the artist’s solo exhibition at the museum. Béna’s work is part of several public and private collections, including Kunstverein Bielefeld, Bielefeld, DE; CAPC, Bordeaux, FR; Fond d’art contemporain – Paris Collection, FR, next to others.