You didn’t follow a traditional art education—how did your journey into art begin, and how has your connection to it grown over time?

When I was very young, I somehow slipped into the film and advertising world. My uncle in Vienna was working on a film set, and they were searching for a little boy, so I ended up with quite a big role at the age of five or six. Later, I joined a youth theater group, played in a teen punk band, and tried many ways of expressing myself: through music, acting, and photography. At home, art was always present in some way: my grandfather, who had emigrated to Canada before my father was born, painted watercolors as a hobby, and my mother also paints to this day. Nobody in my family was professionally involved in the arts, but there was always this atmosphere of creating and expressing oneself.

When I was a child, there was a room in our house where I could paint, and that’s where it started with graffiti, spray paint, and experimenting. My mother sometimes took me to Vienna to see art museums. I didn’t understand the art world at all, but I was fascinated by the scale of the works and how they were made. I remember looking at Gerhard Richter’s paintings with curiosity about their making, and with a desire to experiment with those methods myself. I think between the ages of eight and twenty, I had no real knowledge of art history, but I felt the impact of these big works and wanted to create something that could move people in the same way those works moved me.

Your paintings are not on canvas but on sheets of aluminum. How did you discover this material, and why has it become important to your practice?

It was very pragmatic. My parents owned a small guesthouse with a small local and traditional restaurant, and they used large metal billboards for advertising. When the signs became old and rusty, they were left in our garden. I wanted to make large works, but I couldn’t afford big canvases. So I started taking these discarded metal plates and using them as surfaces. At first, it was technically a disaster; acrylic paint took forever to dry, paint cracked, and the surfaces were flat and difficult. But out of those mistakes, my style began to develop.

One collector still has one of my very early works, a heavy billboard plate that had to be drilled directly into the wall. I overpainted the advertisements with spray paint and collaged materials, creating abstract, large-scale works. It felt raw and exciting. That’s how metal became my surface, and I still work with it.

Did you show your work early on? Did you have “private” exhibitions?

Mostly to family and friends. I also painted backdrops for my band. We even managed to collect some money together and record an EP. It wasn’t about being the best musicians; it was about creating freely. That’s the same attitude I had with painting.

What does the idea of a “garden” mean to you? Your studio is surrounded by nature. Does the environment influence your work?

My studio is almost in the center of town, but when I step outside, I see hundred-year-old trees and a forest-like garden. Sometimes I work outdoors, especially when priming canvases or experimenting. I have large doors that open directly onto this green space, so it almost feels like painting outside even when I’m in the studio. That relation between inside and outside, painting and environment, is very present in my process.

How do you structure your working day?

I used to paint at night, after work. Now I have a clear routine. I wake up early, do some sports, and handle emails and conceptual work in the morning, then go into the studio around ten. I block out eight hours for painting, though in reality, maybe two of those are actual painting time; the rest is watching, thinking, and deciding not to overwork things. In the evening, I stop, clean the space, and prepare for the next day. It took years of mistakes and overpainting to find this rhythm, and it works for me at the moment better than anything else.

Your recent works involve digital processes and AI. Can you tell us more?

I’ve always been interested in collage, starting a work with something already existing, whether a photo, a text, or a fragment. I wondered why an existing image file or a fragment of text can’t replace color. When you look at it later, you often can’t even tell the difference. I’ve always been fascinated by that.

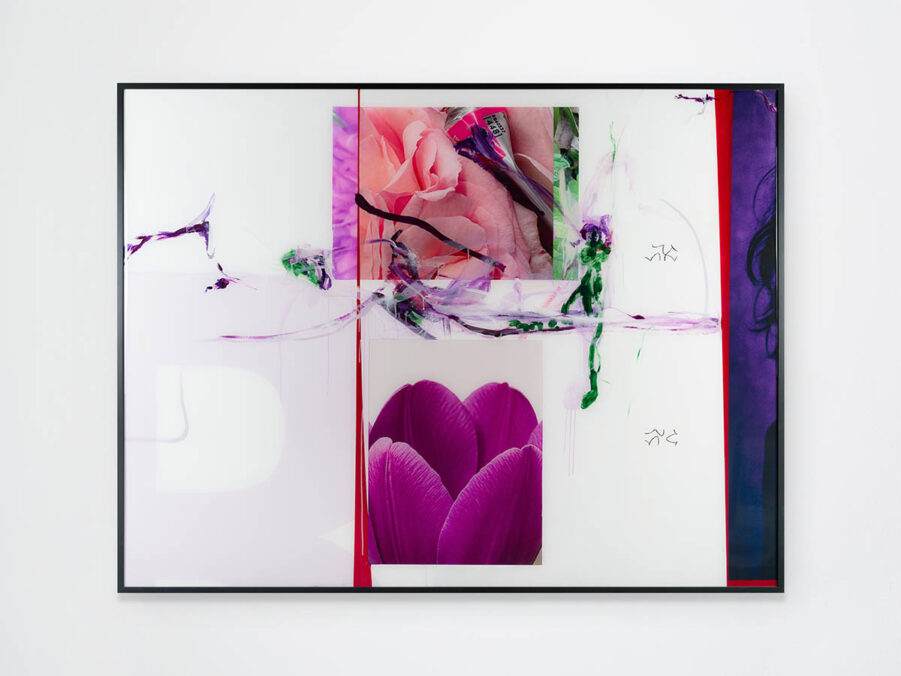

When AI tools became available, I began having conversations with them, describing what I saw and felt, and letting the system generate images. At some point, it even started proposing collages from my own photographs. That fascinated me. Now I work in dialogue with the computer: I give it a size, it generates an arrangement out of AI generated stuff out of my thoughts and my own image files I uploaded, and I then print it and bring the work alive on aluminum. Then I react to that surface with paint. It’s like my algorithm meeting the computer’s algorithm. Sometimes the result is with lots of white space; sometimes it’s overloaded and chaotic. The challenge is to transform this digital starting point into a physical painting that feels alive.

The childlike drawing of a flower, so universal, often appears in your works. Could you tell us more about this motif and what flowers represent to you more generally?

The flower motif comes from childhood. My mother used to draw these simple two-dimensional flowers, and I copied them. Later, when I lived in Vienna, I started tagging them on walls instead of a name. It was quick and universal, and nobody disliked it. Over time, it became a companion motif for me. It carries no grand symbolism; it’s more about acceptance; it always feels “okay.” It is increasingly becoming a motif of engagement for me. I often question it, try to use it differently, sometimes even discard it, only to end up incorporating it in a roundabout way.

I once read in another article that you see your art as open for the viewer’s own interpretation. Do you feel this is the most effective approach, especially in light of the conceptual art movements that have shaped the art world as we know it today?

I want the works to remain open. I love hearing when people see connections between older and newer series; it shows continuity, but I don’t want to apply such a deep meaning to it. What interests me are artists who did things because they felt right, not to fit into a scene. Many people disliked my work for years, and that’s fine. Art should challenge before it becomes accepted. Works by Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst were not always the most accepted, but I appreciate them even more because of that.

You also create editions. How important is this more commercial side of art-making for you?

It’s tricky. Large metal works are expensive to produce and harder to get them out of the studio because not everyone has the space. It would be easier to just make smaller, works, like I managed to do some I really like for the upcoming exhibition, but I prefer to follow my own intuition. At the same time, I’m interested in editions: making works available and accessible to more people. So I don’t see any commercial side of that, or not more than any other artist or gallery program does it. I love to experiment with materials and an approach to create something different. For example, at my book presentation, I created three works in their original size and cut them into smaller pieces, so each person could take home part of an original.

Let’s talk about your upcoming exhibition in Salzburg at Eboran Gallery. How did it come about?

One of my works appeared in an auction at Dorotheum, and the gallerist Joe from Eboran Gallery contacted me afterwards. We met, I visited the space in Salzburg, and immediately had ideas. The exhibition opens on September 19.

For the first time, I’ll show small A4 works—AI-based collages overpainted with watercolor, oil, and acrylic—alongside large aluminum pieces. There will also be a site-specific wall installation: parts of the painting will be printed directly onto the gallery wall, with works hung over them. The layout itself was suggested by the AI, including a mistake in alignment that I decided to keep.

We’re also making a film of the exhibition with friends, so I’ll spend a few days in Salzburg for the setup.

Finally, what motivates you most at the moment?

To keep discovering. Especially in the current world where everything is changing so super-fast, I’m curios what the future will bring, even when I m a little afraid of that. Imagine having a robot helping you do the work in the studio or whatever… Whether it’s the current series, working with AI, or experimenting with different materials, I want to find new ways of expression. For me, it’s about keeping the curiosity I had as a child, looking at something and asking, How or why is this done, and How can I make it my own?

Exhibition: John Petschinger: zweimal lila ist auch nicht gleich

Opening: 19 September 2025, 19:00

Duration: 24 September – 10 October 2025

Address and contact:

Eboran Galerie

Ignaz-Harrer-Straße 38, 5020 Salzburg

www.eboran-galerie.net

You can also read our earlier interview with Eboran Galerie here.

John Petschinger – www.john.art, www.instagram.com/johnpetschinger

John Petschinger, an Austrian artist born in 1994, works with large-scale works on aluminum, where raw material meets layers of spray paint, collage, and overpainting. His practice bridges analog and digital processes, often incorporating AI-generated compositions as starting points for physical transformation.