Vincent, how did you first come into contact with Kessler’s work, and how did the idea for this exhibition begin?

Vincent Weisl: Several years ago, I curated a show on park benches. At that time, I was looking for an artist who was dealing with benches in public spaces. Everyone pointed me toward Leopold; people kept saying, “Go to his studio, he works exclusively with public space.”

When I finally went there, it was like being a child in a toy shop. His studio was full of drawings, sketches, and photos of works. We talked for hours, and I selected a bench-related piece for that exhibition. But more importantly, I was fascinated by his overall practice, 25 years of consistently working outside the market, yet always with a clear, strong focus on public space. His interests developed in different directions, but they always came together in a way that made sense. The Wien Museum hadn’t done a solo show with an artist in almost ten years, so I began discussing the possibility of doing solo shows again with our director, Matti Bunzl, who has been following Kessler’s work for over 20 years. From the very beginning, he was excited about the idea and offered his full support.

His work also feels very Viennese, especially the pieces from the early 2000s, which respond to things happening in Vienna’s public space. At the same time, his travels as an artist opened perspectives on other cities. For instance, he did a piece in London in 2006 dealing with surveillance, which wasn’t a big topic here at the time. All these different aspects made this show his mid-career retrospective show.

Leopold, you were already very active in your student years and continued consistently afterwards, and now the exhibition gathers together works spanning almost twenty-five years of your practice. I think that your works don’t feel especially tied to a specific moment. They don’t demand to be read as “historical” or “past” actions, but could still be made today. How was it for you to work with a curator and exhibition designers on bringing all these works together?

Leopold Kessler: I didn’t show much in the last years, so for me this was a very special situation. I had some larger shows about fifteen years ago, but never anything like this – twenty-five years of work combined in one exhibition. Normally, I always tried to keep each piece self-contained, “self-standing,” not really relating to the others. But here the process was different. Working with Vincent, the curator, was great. My first instinct was to keep it very simple: select the works, put them on screens, and that’s it. But he kept insisting on thinking about combinations, about the meaning that emerges when works are seen together.

We spent more than a year discussing, experimenting, and slowly, I also began to think in terms of relations between works. Certain connections became clear: early interventions were much more about infrastructure; later ones were interactive, involving people; and then a third chapter developed around cultural objects, models, and sketches I had never shown before.

Exhibiting public space works inside a museum is always a challenge. How did you two together approach this translation?

Vincent: We wanted a simple design, but also created a kind of spatial atmosphere. The aim was not to show “video installations” but rather to make visitors feel like they were actually stepping into public space. One major question was the size of the videos. We experimented with small, TV-like screens, like you might encounter in everyday outdoor settings, versus large-scale projections. Each choice changes how the work is perceived and valued. Sound was equally crucial: the overlapping city noises create the impression that you’re in the streets. We also decided to only use materials and forms that are already available at the museum, without building new structures. That choice kept the presentation grounded and connected to the institution.

Could you walk us through the structure in the space? Was there a chapter-like orientation of the rooms?

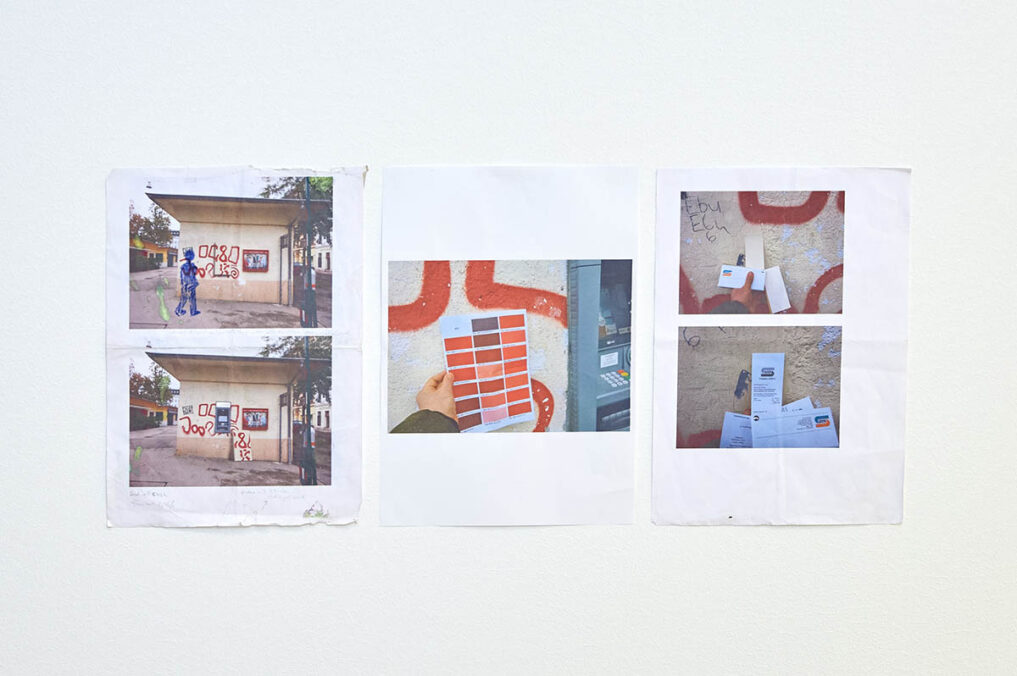

Vincent: We wanted each space or part of the space to feature at least two works in dialogue with each other. For example, in one area, we paired two pieces dealing with graffiti and social separation playfully. In another, we focused on modern infrastructure. The goal was always to create subtle connections without overexplaining them with wall texts. We wanted visitors to draw their own connections and conclusions. Certain topics repeat across rooms, but never too often. There’s also a “studio-like” section, which highlights the research and preparatory work behind the actions. It was important to counter the impression that these are minimal gestures done spontaneously in public space; in fact, there’s a deep process leading up to them.

There is a moment in the exhibition, all of a sudden, on all screens, a video appears, filmed from a great distance, of a group of people dancing the Walzer surrounded by nature. It created a kind of break in the show. It stood out almost as an intervention within the exhibition, maybe even a political statement inserted into the institutional frame.

Leopold: Leopold: Vincent was always pushing: “What’s the difference if people come to your exhibition compared to watching it online?” And I said, of course, it’s different, you experience various videos spatially, not by scrolling. Then I had the idea: what if, occasionally, all videos were interrupted by one identical scene? That’s how Neighbors came into play — a work from 2008. I re-enacted a waltz-dance by multiple couples on the terrace of a baroque palace – Schloss Hof. I saw this scene at a newyears concert broadcast. This palace is right at the border to Slovakia, and you can see the socialist blocks of Bratislava from there. The video has no cuts; it is shot from a hill on the Slovak side, panning over the socialist blocks, across the border, which is a small creek. Then there is a zoom towards the terrace, and this unreal, fata-morgana-like scene appears.

It’s funny: I never showed it in Austria before. It premiered in Sweden, Spain, and Poland. Back then, nobody cared because it felt so specific to Austrian identity, which is a small-country topic. Now, 18 years later, it has aged very well. With the political shifts, Austria imagines itself as an “island” again, and the waltzing becomes a perfect metaphor. This dance, ignoring reality, denying it, feels even stronger today than when I made the piece.

I read recently that there are more than four hundred different balls held every year in Austria. Astonishingly, this remains such a strong social ritual. How did you approach that dimension in Neighbors?

Leopold: I had to find a dance school willing to travel and perform for very little money. They were immediately enthusiastic. What surprised me was realizing how much it matters in Vienna which school you attend. It carries meaning, it reflects your social status, and how the city is layered: old bourgeois families, social democratic traditions, immigrant communities, and newcomers like me who had no idea about these codes. And yes, it’s also the only work I’ve made outside an urban setting. That shift, the countryside setting, and the quiet break also influenced the exhibition for sure.

Public space naturally brings questions of politics, economics, and social roles. Would you say Kessler’s works tie into Viennese traditions of politically engaged art?

Vincent: You could connect his practice back to the Viennese Actionists in some way, if you want — though Kessler’s approach is more playful, inviting the public to interact rather than confront. His works always carry political undertones, but they remain ambiguous. Take, for instance, the piece about being placed in a luxury hotel while making political work; it raises questions about the artist’s role, privilege, and responsibility, but it never preaches. Children can enjoy the works at face value, while adults can interpret them through social or political lenses. That layered quality makes the work so strong. I’d also say his position is unique: many artists today are either extremely political and explicit or working more formally and abstractly. Kessler is one of the few who navigate that in-between space.

One quality of the works is their lightness, the way heavy topics become approachable. Do you see this as key to why they work so well in the museum context?

Vincent: His works are accessible without being simplistic. Even though he comes from sculpture and conceptual art traditions, the outcome has a kind of ease, as you say, lightness that opens the doors to many different audiences. This is a historical institution with a civic collection, and his works connect the history with the immediacy of contemporary urban life.

The cigarette piece, that is one of my favorite pieces in the show— how did that come about?

Leopold: It started from an invitation to a group show that was traveling between cities, a kind of curatorial concept about the nomadic artist. For that show, the organizers wanted half the artists from the venue and half new. I disliked that curatorial setup; there were so many expectations about what artists have to do: live in a metropolis, travel to the Global South, and I resisted that. I didn’t want to be forced into the label “nomadic artist.” So my idea was a kind of refusal: I made work that didn’t require me to leave.

My venue was in the town closest to Vienna — Budapest. I decided to use the existing train infrastructure: Something should be stuck onto the train and used as a moving carrier, an unintended transport. Cigarettes fit the concept because they’re a daily supply, instantly consumable. There’s also the cinematic thing, smoking “works” on camera; directors know that it reads a certain way. A small element of the idea was that smuggling cigarettes from Eastern Europe can be cheaper, but I didn’t want to emphasize that. It’s more about routine and the everydayness.

We filmed for maybe a week. The process became routine. The people in Budapest (the Curator was Edit Molnar) had the hard part: attaching the cigarettes on the train was far more suspicious than my job of collecting them. We’d agreed on the schedule with the trains. My collaborators would text me saying, “It’s sticking.” Then I had three hours to come to the station and pick them up.

How do accidents and small variations affect the work? You mentioned camera positioning on the train.

Leopold: Small deviations are part of it. In the cigarette piece, the camera was on a tripod at a precise spot. Trains don’t always stop at the same spot. Jan Machacek, a friend and colleague who did the filming, would adjust the camera, zoom in, or reframe when needed. The cigarettes arrive at the camera; they come to the viewer. The camera’s position is the viewer’s position. That’s what I try to transport: not my subjective experience of doing it but a positional perspective for whoever watches the video.

You mentioned the piece is connected to place and time, but could also be anywhere. How do you approach site-specificity and context?

Leopold: I don’t usually dig into the deep history of a place. I try to find elements that are already there and common, things people know without needing background reading. Of course, the more you know, the more layers you can find, and sometimes you discover histories I hadn’t intended. For example, Vienna–Budapest has geographic and historical resonances, but my connection to it was partly practical and partly geographic. Bringing cigarettes from Amsterdam to Vienna would have been nearly impossible logistically, and also would have changed the gesture. I prefer to use what’s already available in a place and make a simple connection.

For your practice, what matters more: the action, the concept, or the documentation? Is the video the work, or is the action the actual work?

Leopold: That’s a question I get a lot. There is a physical action. But as the interventions are normally not authorized, there is no live audience. Only random people see parts of it. So, the video plays a central role from the beginning.

How do personal experiences inform your material decisions? There are objects in the exhibition that react to body temperature.

Leopold: I often start from an experience. During the pandemic period, I encountered a wall device with LED lights that reacted to body temperature; it registered me before I even analyzed it. That made me feel seen and also exposed: the green light meant “okay,” but what if it turned red? That ambiguity, between detection, approval, and control, became the starting point for a new work. My “Indoor-Thermolith” looks a bit like archaic steles; they also react to visitors‘ body temperature- if they come too close.

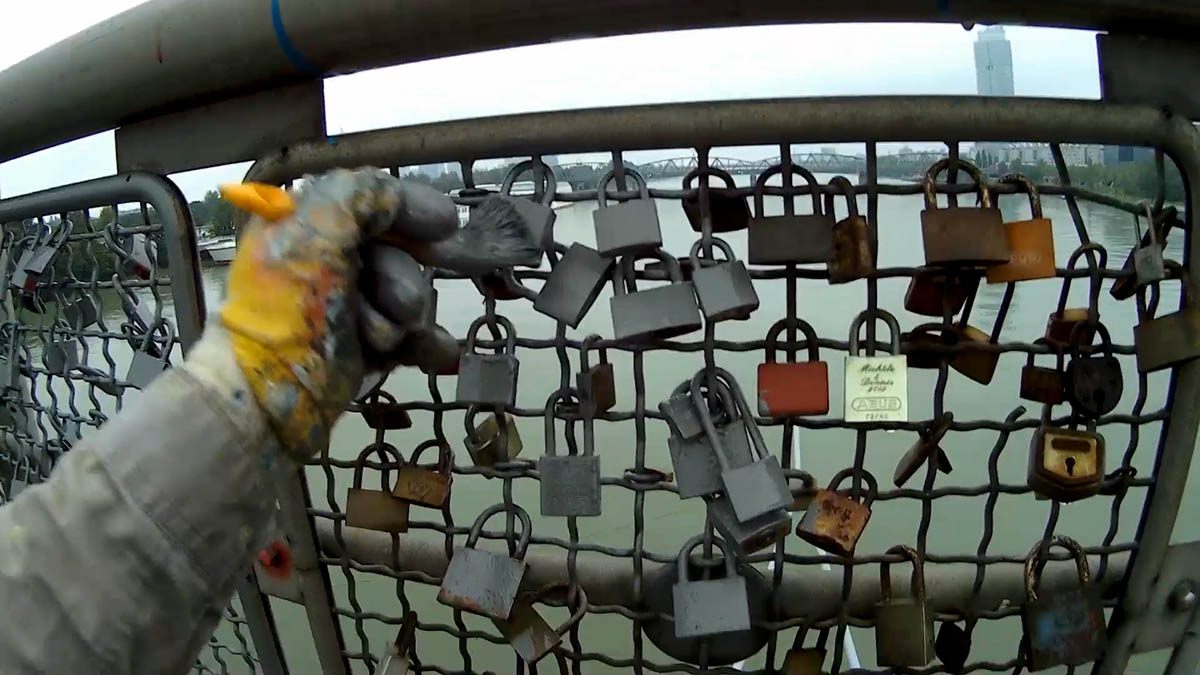

And what about the love locks on the bridge? It is a video filmed from an ego-perspective. How did that come about?

Leopold: I was interested in these lovelocks as a private initiative of people. They represent individuality, yet they come in crowds normally. By painting them in the color of the handrail rail I integrate them into the infrastructure. I had the camera in one hand and painted with the other, so the recipients have my perspective. They almost become a hostage. It’s a brutal video: one decides over dozens of others.

Many of my works reflect the importance of institutions by ignoring their authority. They show what happens when they are missing. The video shows how these locks are vulnerable- unprotected. There’s no democracy in that action. One year later, some of the paint had been scratched off, also new locks had appeared, bright and shiny among the grey ones.

In many of your works, you deal with masses, groups, and systems. But I also notice fragile, poetic details, the graffiti and ATM piece, or the chimney project.

Leopold: I organized a “smoke-show” with the chimneys of a communal building in Vienna. On the roof, there are dozens of individual tubes, each connected to one individual or social unit. I wanted to draw attention to this by creating colored smoke to specific tubes. People came out of their houses to watch, to see their own chimneys. It highlighted individuality within the collective.

Exhibition: Leopold Kessler: Works in Public Space

Curator: Vincent Weisl

Exhibition duration: September 11, 2025, until May 17, 2026

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday 10 am–6 pm

More about the exhibition: www.wienmuseum.at

Address and contact:

Wien Museum MUSA

Felderstraße 6–8, 1010 Vienna

www.wienmuseum.at

Leopold Kessler, born in 1976, lives and works in Vienna. He studied sculpture in Munich and Vienna, where he graduated in 2004. His work deals with psycho-social phenomena that gain a political dimension in public space. The implementation of his works is carried out through unannounced interventions, objects, installations, and videos. www.leopoldkessler.net www.instagram.com/leopold_kessler/

Vincent Weisl is a curator at the Wien Museum. He is involved in exhibition projects ranging from contemporary art to cultural and social history exhibitions. In recent years, he has also been part of exhibition projects in Germany (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin) and in Serbia (Museum of Yugoslavia). Vincent’s academic focus is on art in the context of historical politics and art in public space