What is your relation to Otto Neurath, and how did you come to think about his exhibition Society & Economy, which dates back a hundred years? What was the urge behind it?

My interest in Otto Neurath already comes from my previous studies in philosophy in Belgrade. There were many people in the department who were working on the Vienna Circle and Logical Empiricism. At the time, I was not reading so much about Otto Neurath from the perspective of the social sciences or the economy. What I nevertheless found and still find striking was his involvement in actively shaping society. That was quite unconventional, highlighting his unique position within the circle and in a way a direct reference, if not continuation of Constructivist efforts.

And then, when I started studying at the Academy, I noticed the inspiration in the ISOTYPE, mostly from the side of design and architecture. What I still come back to is the idea of a unified language, broken down into its base, written and communicated visually.

It took some years until I could get this concept into an institutional framework. My diploma in 2020 was supposed to be Otto Neurath’s museum model, but then I decided to pursue another opportunity. The diploma presentation space at the Academy would not have had the same context and effect. The historical model and working on/with this framework is the basis of the show you can currently visit.

That’s why it is important to mention that our exhibition takes place in the Museum space, which was a former canteen of the Rathaus. And the initial display, the permanent exhibition conceived by Neurath and the team, was in the Volkshalle, which is pretty close, and also part of the same institution. When you do a show about Otto Neurath, it somehow has to be representative, because of his status as, even though a double-prosecuted national hero. And then, there is also the question of who is even considered to actually give impressions or work on such an important, representational, party-related, and, if you will, topic of national relevance. We know the answer. That is why it took a long time until it actually came about—that someone who comes from the periphery of the Monarchy context could review some points and gaps within the official narrative.

Next to curatorial, you also had an artistic involvement in the exhibition – tell us about the display you made especially for this show.

The structure or the display was made in collaboration with FANTOPLAST out of completely recyclable plastic. It doesn’t look massive because of the color, but it is a compact structure that serves as a display for the artworks. Instead of focusing on re-staging the model of the historical structure itself, originally designed by Josef Frank, some recognizable elements were kept, although the panels were used in a different way. The structure, consisting of cut panels, made it not only visually lighter by providing a lot of negative/open space, but is also different from the dark oak version.

How did you decide on its form and color, and how should visitors move through it?

There’s no prescribed route through the show. The structure makes you move, but it doesn’t completely regulate how. We also considered accessibility and had to adjust to the spatial features of the space. The white color came as a solution to not occupy, but rather to provide space. It is a kind of visible infrastructure. Together with the artists, we looked at the historical exhibition model, but also adapted it, the same with the artworks. Some, like Florian, based dimensions of the work on the structure, but also visibly adjusted the structure; the work of Vasilena is made from the same material as the display. Natalia, on the other hand, completely broke it apart as a commentary. People often say the white looks “institutional,” and yes, it does—but with a twist. It’s a working-class museum structure, not a bourgeois white cube. Neurath never used the term “working class museum”; he called it a social museum or museum of the future. For me, though, it’s always been a museum by and for the working class, not about it. That distinction matters.

If the structure is made out of wood and the execution was dimly lit, it would give more of that traditional, historical setting we’re used to. But here, it feels like a contemporary way of approaching the idea of museum display. What about the works that are displayed within it?

Here is probably where my artistic role comes in. At first, the idea was to do it as a single person project, but I was not really interested in reworking ISOTYPE pictograms. That was not what I was drawn to. I was more interested in the holding structure and providing a framework. In the last few years my work has been very much about (re)constructing frameworks, which is also what I was doing as an artistic director for four years at WIENWOCHE. My job was to challenge frameworks, propose counter-narratives, and bring perspectives together.

When there was an open call for MUSA, I applied with a collaborative-curatorial project. And then I thought—what if I still created this structure, but then brought in artistic positions and put them together to work on related topics. The list of the artists was already clear—I knew from their practices what could work with some suggestions from my side. I didn’t want them to go far from their own practice. The works are their own comments, best discussed by the person who made them.

In Neurath’s terms and analogies, the project is an orchestration of different approaches of artists who are deeply involved in the transformation of society. It’s all new artworks based on specific historical facts around Otto Neurath, around ISOTYPE, and the exchanges, for example, as part of the War Ministry during the Monarchy times, Neurath traveled to the Kingdom of Serbia to test his war economy concepts during the Balkan Wars. Neurath was assigned to “commodity provision,” a continuous approach of extraction that links us to the contemporary context in Serbia and the Balkans.

The structure also connects to your ecological concerns, right?

Exactly. It’s built from recycled plastic, completely reusable. Once you remove the screws, it can disappear entirely. That’s why we didn’t make a catalogue, it would contradict the ecological stance. The museum already has a graveyard of displays, so we wanted to work with reusable materials. Even the handouts were cut—paper waste is a real issue. The decision was clear: no catalogues, no flyers. The whole exhibition should function in a “green museum” way, something that the Vienna Museum is working on implementing.

Another fact worth mentioning here—from photos of extracted landscapes, to coniferous tree pictograms and dried plant stems—there is a set of natural elements gradually included in the show.

What is important is mirko nikolić’s work. You were working and exchanging literature all the time. Are those texts we see in the exhibition something that came from your conversations, or are they found materials?

The list of texts mirko and I were reading became part of their artwork. The excerpts are from writings of Neurath juxtaposed with contemporary sites of extraction, like Jadar, Bor, Majdanpek, and Smederevo in Serbia. The historical and contemporary layers are linked, which directly connects us to the war economy. The concept of war economy is central to Otto Neurath—and is surprisingly the base of all his museum work.

During war, production is in full swing, and everything is made in a way that the necessary and basic things are produced to serve the needs of the most people. Neurath thought that this could be translated into a peace economy, where everything would still be serving the people. But what usually happens, and what we’ve been witnessing all these years, is that fueling war is profitable. War is a base for nation-state self-sustainance. Transitioning into peace—I don’t even know whether this is a realistic topic anymore. War activates production lines for the profit of the few. It is disproportional to the interests of the people.

Tell us about the individual works in the show?

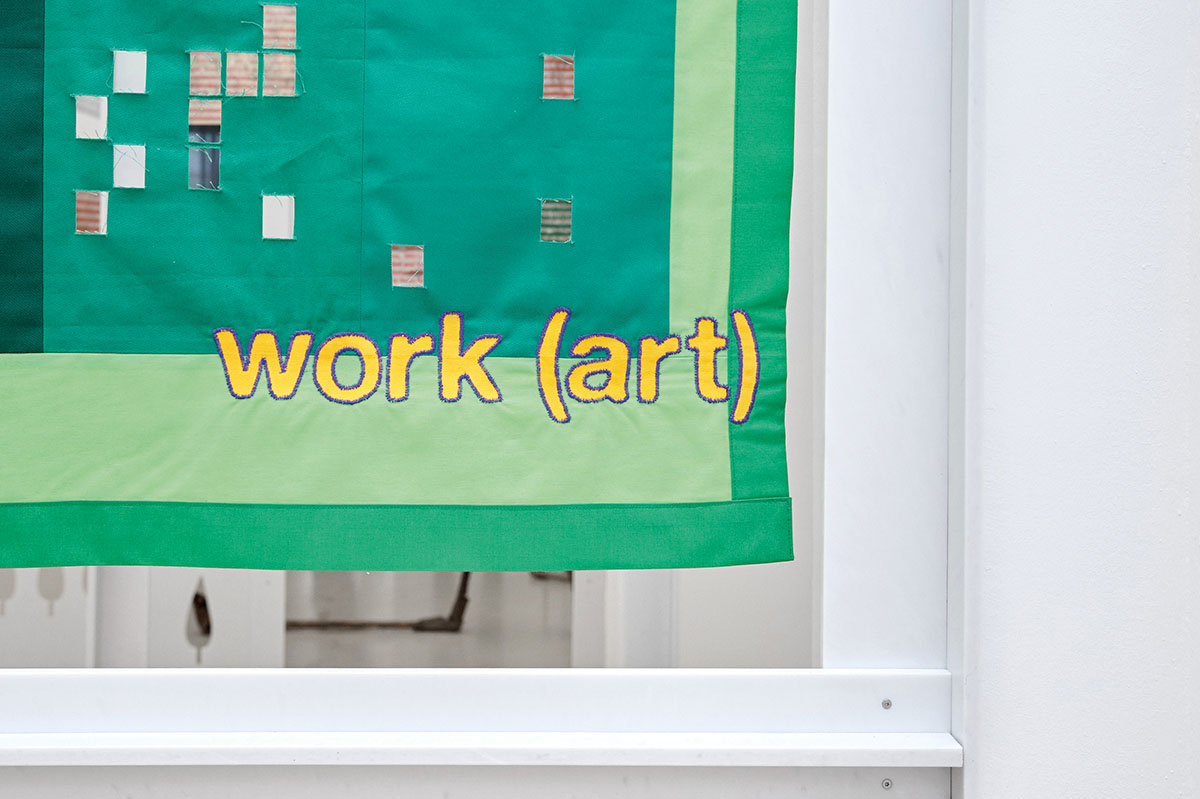

The show was meant to be a small, contemporary exhibition, but when I started working with historical excerpts, it turned into something else. It turned into a discourse between art, history, and politics. You have Florian Mayr’s works; he comes from a commercial gallery background, but he is also an artist, a parent, and works as a technician supporting other artists. mirko nikolić is a climate justice activist concentrated on undermining and extraction issues. Vasilena Gankovska brings post-socialist visual language from Bulgaria to Vienna and uses it in her take on ISOTYPE from the urbanist viewpoint. Natalia Gurova has a strong connection to Russian Constructivism and is involved in challenging power structures.

At first, this could seem like a “typical Eastern European constellation,” but I don’t think it is. No one is performing victimhood here—it’s more of a direct, critical attack. Every position brings in subtle gestures that reveal and build on problematic layers. For example, Florian Mayr’s work is deeply personal. He documented his working hours, including his care work as a parent, which is revolutionary for someone embedded in the commercial gallery world. Then mirko’s project works with texts and photos of current extraction sites in the Balkans, connecting them to Neurath’s war economy studies. Their “poetic intervention” reads these landscapes as contemporary continuations of imperial logic.

On the other hand, Vasilena Gankovska uses hatch patterns to visualize the urban transformation of the Seestadt, which is an ongoing topic of her research. The work also contains statistics on the distribution of green spaces in relation to the number of inhabitants in Vienna. Artwork by Natalia Gurova was originally planned in cardboard, as a reference to El Lissitzky’s unrealized paper structures. Her work, Giant Hogweed, refers to a plant brought as a diplomatic gift to Austria by the Russian Tsar during the Vienna Congress—now invasive and poisonous. It’s a metaphor for the unintended consequences of cultural exchange and power.

If I criticize myself, I’d say that one of the things missing in the exhibition is a deeper engagement with Neurath’s role in the Munich Soviet Republic. During the trial, he claimed that he was only a “social technician” and that the engagements were not ideological. Funnily enough, his ideas remain paradoxical—idealistic, at times also utopian—yet shaped by power.

Exhibition: Society & Economy; Contemporary Positions on Otto Neurath. curated by Jelena Micić

Artist: Vasilena Gankovska, Natalia Gurova, Florian Mayr, mirko nikolić

Display design and realization: Jelena Micić and Fantoplast

Duration: October 30, 2025 – May 17, 2026

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday 10 am–6 pm

Address and contact:

Wien Museum MUSA

Felderstraße 6–8, 1010 Vienna

www.wienmuseum.at

More about the exhibition: www.wienmuseum.at

Jelena Micić is an artist and artistic director of the festival WIENWOCHE (2022- 2025). Awarded the YVAA — Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos Award (2021), the Ö1 Talentestipendium Bildende Kunst, and the kültüř gemma! Fellowship (2018). Doctoral studies at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (since 2024). Their curatorial interest addresses the struggles of non-citizens, labor migration, and relations with the global majority. On the other hand, their artistic practice focuses on the politics of material and socio-economic aspects of (color) systems. Lives and works in Vienna.

Vasilena Gankovska (b. 1978 in Troyan, Bulgaria) lives in Vienna since 2001 and works as visual artist. Degree in Fine Arts, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and MA in Arts, National Art Academy Sofia. Multiple exhibitions and awards, amongst others in Vienna, Berlin, Sofia and Los Angeles. Her artistic work deals with the different aspects of the urban life, leisure and work and their spaces. Gankovska navigates between different media such as painting, drawing, ceramics and installation. The artistic research includes city walks, derives and short texts which accompany her so-called “visual notes”.

Natalia Gurova (b. in Belarus, raised in Russia, since 2014 lives and works in Austria) is a temporary journalist and permanent artist multidisciplinary practice encompasses sculpture, printmaking, drawing, poetry, site-specific installation, and curating. Gurova studied journalism at Moscow State University and worked in Russian media for over a decade. From 2014 to 2018, studied site-specific art at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, followed by object sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (2018–2025). In 2021–2022, co-developed an exhibition program at the Academy’s Department for Contemporary Art with Vik Bayer. Since March 2022, she has worked with Office Ukraine in Vienna, supporting Ukrainian artists displaced by war. She is interested in how things are connected and disconnected, how people see each other, what is the role of facts and narration, how to be lonely and being in contact, and how structures form and collapse.

Florian Mayr (b. 1982, Wels) is an artist living and working in Vienna. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where he completed his diploma in 2019 under Heimo Zobernig in Textual Sculpture, following earlier teacher training with Martin Beck, including archival research in New York on Christopher D’Arcangelo’s practice. Mayr’s practice is situated at the intersection of social observation and artistic form, where material choices reflect economic realities and biographical experiences. His work centers on the entanglement of life, labor, and art, articulated through the recurring framework of work, work, work—referring to paid labor, care work, and artistic practice. Drawing from his own lived experience, Mayr explores how time, economic precarity, and social conditions shape artistic production. He emphasizes relational structures over personal sentiment, highlighting the broader systemic pressures that define how emerging artists live and work today.

mirko nikolić (b. in Yugoslavia) is a visual artist, environmental justice researcher and organiser. nikolić holds a PhD in Arts & Media Practice from the University of Westminster, and is currently a researcher at Södertörn University. Through site-specific intermedia performances and critical writing, often as part of different groupings and constellations, nikolić seeks prefigurations of environmental and climate justice.

Fantoplast, founded in 2022, is dedicated to transforming plastic waste into valuable and sustainable products, achieving an 80% reduction in carbon emissions compared to the use of virgin materials. Its five founders — Max Scheidl, Raphael Volkmer, Alessia Scuderi, Julian Jankovic, and Florian Schäfer — bring together expertise in design, art, plastics engineering, and business administration. United by a collective approach, they address the issue of plastic waste through sustainable production, educational initiatives, and collaborations across the arts and cultural sectors.