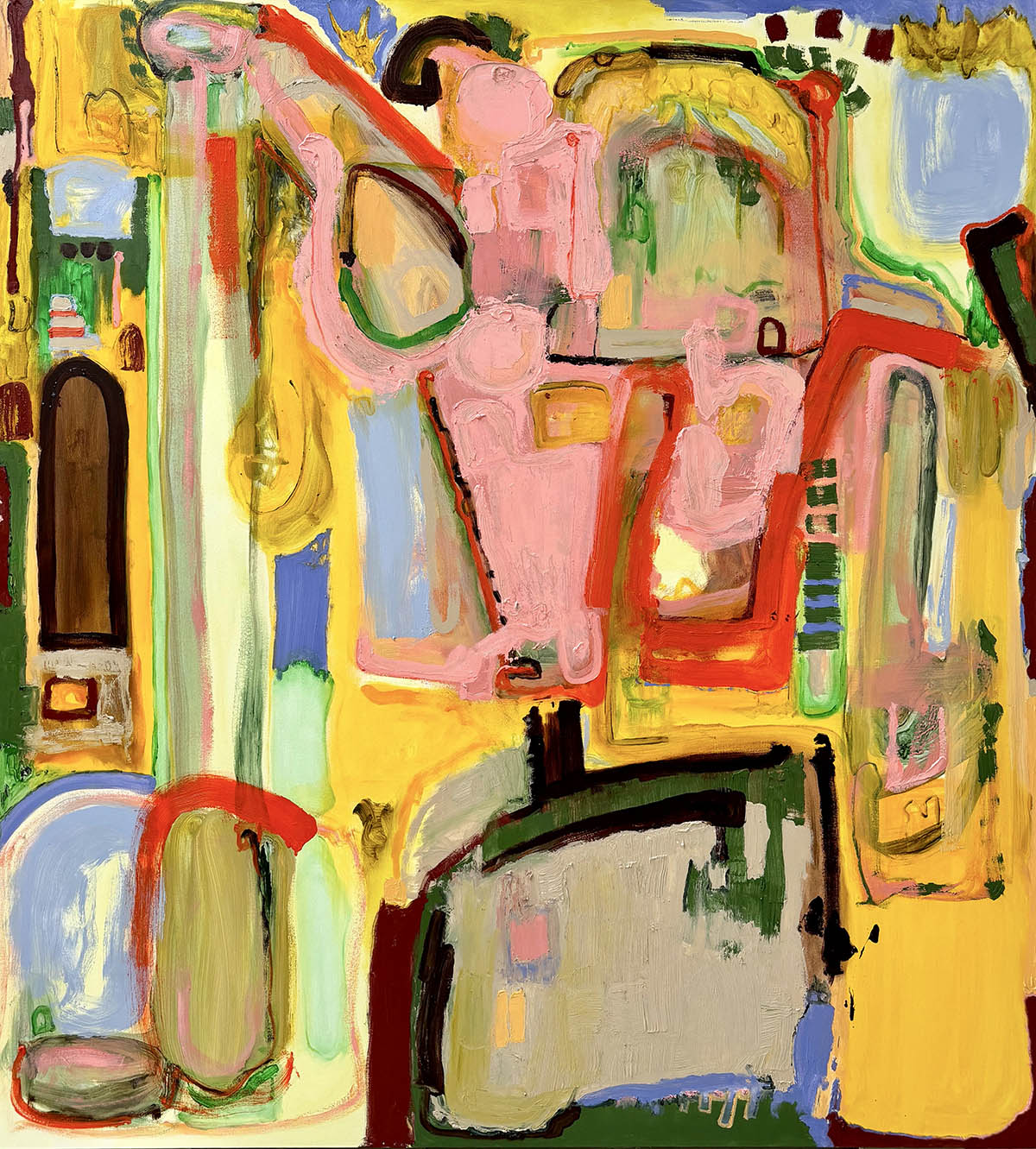

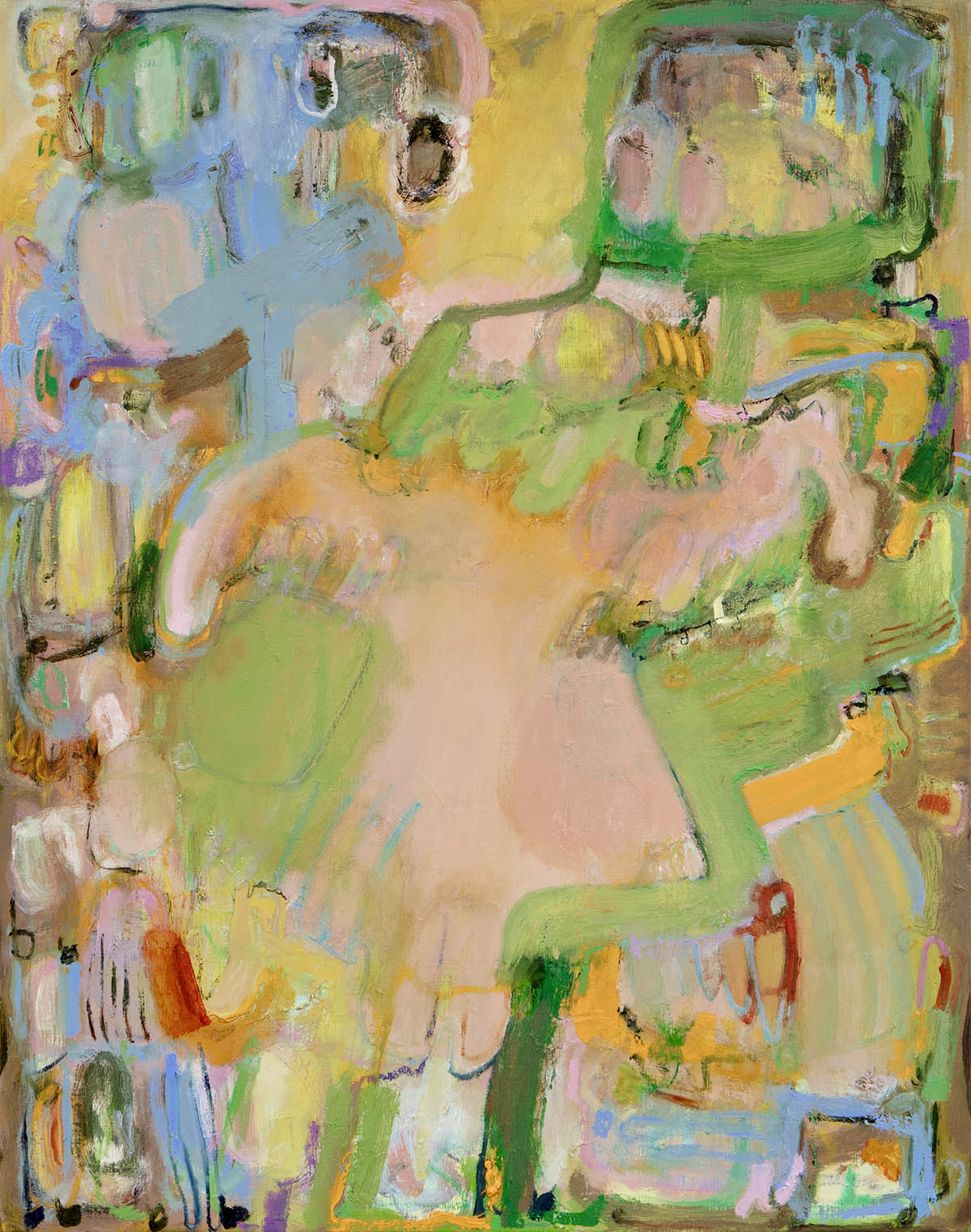

Sweeping gestures give way to compressed, insistent marks; periods of speed interrupted by hesitation and reflection. Paint is applied, scraped back, and reintroduced, surfaces seesawing between density and exposure. Colour is drawn out through appetite; pigments that feel edible, evoking taste, texture, and excess. Works exist in a continual state of flux, hovering between abstraction and somatic suggestion, where forms surface briefly before dissolving, as if caught mid-transformation. Brushstrokes function less as representation than as residue: traces of emotional exertion recorded through sequences of unconscious physical reactions. She describes approaching the canvas “as a surface that holds sensation outside the body“, the painting becoming a container for corporeal tension, an inhabited structure where sensation is displaced, reworked, and transformed rather than confessed. It is through this ongoing negotiation between body and material that Hennessey’s work opens up a space for release and renewal, not as resolution, but as a continual process of reappraisal.

After completing your BA in Fine Art at City & Guilds of London Art School, you are now continuing with an MA in Painting at the Slade School of Art. How has the institutional framework of these art schools influenced your practice, both materially and conceptually?

City & Guilds and the Slade have shaped me in very different ways, and I’m grateful for that contrast. City & Guilds felt protective and quietly generous. I never loved the intensity of central London, and the school had this village-like atmosphere where things could unfold slowly. Not knowing was allowed there, even encouraged. The tutors were attentive without being prescriptive, which made risk feel possible rather than performative. I felt held in a way that let me wander, get lost, and take time to work out what actually mattered. That patience still sits at the core of how I work.

The Slade has offered a different kind of expansion. It’s permitted me to think bigger, materially, and conceptually. Working at scale, especially on murals, has pushed my process toward something more physical and choreographic, where movement and rhythm matter as much as the image itself. It’s also where I’ve been able to question my material choices more rigorously. I found my way onto a medical humanities module, studying alongside trainee doctors and thinking about the body and death from perspectives far outside the art studio. That space to step sideways and to write has really sharpened my practice. For me, what connects both institutions is generosity. At their best, art schools create a space where attention can circulate, where conversations carry weight, and where uncertainty isn’t something to hide from. I feel lucky to have been in places that trusted that process, and I think that trust is what’s allowed me to take risks without needing to resolve everything too quickly.

You work primarily with oil painting. Can you talk us through your process to the final stages of a painting?

I begin with a sense of urgency. The start of a painting needs attack and rhythm, a kind of focused momentum where I am not yet thinking about resolution. Oil paint is so mutable that it allows me to work from the body rather than the head. I can apply it with force, scrub it in, scratch and scrape it back. At this stage, the paint almost finds its own path. It slips, sinks, resists. I try to stay close to that movement and not interfere too quickly. As the surface builds, I begin to test its limits. I push the painting toward a point of destruction, adding too much, burying things, letting forms collapse under their own weight. I often return to the question that sits at the centre of my practice. What if I were full of paint? How would it settle in my bones, in my chest, in my throat? Thinking this way keeps the process embodied. The painting becomes less about making an image and more about moving sensation around inside a structure.

The final stages feel very different. After the excess comes a kind of repair. It becomes slower and more careful, almost surgical. I start to pick things back out, to tend to what has survived. These moments feel delicate and vital, like trying to stabilise something that has been through trauma. I am not trying to restore order completely. I want the painting to carry the memory of its own undoing, to hold both the violence of the making and the care of the repair at the same time.

The colours in your paintings feel wild, fresh, and emotionally charged. How do you choose your palette, and what role does colour play in shaping mood or meaning in your work?

I’m drawn to colour first through appetite rather than symbolism. Certain colours feel edible to me. They suggest taste, texture, and excess. Oil paint carries that tease of consumption, the way it can look like butter, grease, juice, candy, something rich and slightly improper. I’m interested in that moment where colour sits between seduction and saturation, where it promises pleasure but also hints at the risk of too much. Mood comes from that tension, from the push and pull between desire and fullness.

Colour is also tied closely to how I think about change. The way I title paintings often comes from everyday moments of transformation, those small shifts where it feels possible to leave an old state behind and begin again. Painting works like punctuation in that sense. Each canvas marks a pause or a turn, a clearing of space. The palette carries that feeling. Some colours feel newly born, clean, almost naive. Others feel excavated, heavy, sedimented, as though they’ve been pulled up from somewhere deep and old. There is also a physical logic to it. Colour has weight. You feel it when you squeeze a tube, when you lift a finished canvas, when certain pigments drag or resist more than others. I think about colour the way I think about sensation or emotion, as something that exists on a frequency. When I’m painting, I use colour almost like a recipe, adjusting ratios, adding, or withholding, seeing what needs to be balanced. Meaning arrives through that process, not as a message but as a felt state that settles once the surface has found its equilibrium.

Bodies frequently appear in your paintings. Who are these figures, and how do you approach representation without fixing them into singular identities?

The figures are a distant form of self-portraiture, but with the attention reversed. Rather than thinking about how I appear to others, I am paying attention to how I appear to myself from the inside. What the body is holding, what it feels like to move through space, where pressure gathers or disperses. That inward focus makes the act of painting feel intimate, because it does not rely on an external gaze or even on a projected version of myself. I am not trying to be seen. I am trying to notice. Because of that, the figures resist being fixed into singular identities. They are not characters or representations of particular people. They emerge through sensation, through paint being pushed, stretched, buried, and rearranged. Over time, they become ambiguous, even to me. They shift in meaning depending on when and how I look at them. I like that instability. It allows the body in the painting to develop its own logic, its morphology, revealing only what is necessary in that moment. In the end, the figures become less about who they are and more about what they can hold. They act as mirrors, reflecting something to the viewer and back to me, without insisting on a single reading or a fixed self.

Your works often suggest strong psychological states. To what extent are your paintings informed by autobiography? Where does imagination or projection take over?

I don’t think of the paintings as autobiographical in a literal or narrative sense. They are not records of events or personal history. If autobiography enters, it does so through sensation rather than story. What I bring into the work is the residue of lived experience: pressure, fatigue, anticipation, hunger, containment. These are psychological states that come from being inside a body over time, not from specific memories I am trying to depict.

Imagination takes over quite quickly once I am painting. The body I am working with on the canvas is not exactly mine, even though it begins there. It becomes a proxy, a stand-in that can absorb and exaggerate feeling without consequence. Projection allows me to push those states further than I could in life, to test what happens when control loosens or when something is overworked, buried, or pulled apart. The painting becomes a space where internal experience is reconfigured rather than confessed. It is less about telling the truth of what happened and more about exploring what it feels like to be inside certain states and letting them mutate into form.

Your scenes often feel intimate and inward-looking. How conscious are you of constructing emotional or psychological spaces within the painting?

The studio is important in this. My relationship to it is architectural and bounded. When I enter, I cross into a space where I can let go of external perception. It receives me without the eyes of the world. That enclosure allows me to focus on sensation rather than appearance. I often think about John Cage describing to Philip Guston how, when you begin to paint, everyone is in the room with you, teachers, critics, the past, and then one by one they leave, and if you keep going, even you leave. That is the moment I am waiting for. When I step into the studio and then into the canvas, I feel as if I leave my skin behind and inhabit another structure, one made of fabric and flatness.

Inside that structure, emotional space is not something I construct so much as something I enter. Weight and gravity begin to feel unstable. Inside and outside blur. The painting becomes a container for internal pressure, a place where emotion can sit without being explained. Intimacy comes from that withdrawal from the external world, from allowing the canvas to function as a closed room where feeling can accumulate, be stored, and quietly rearranged.

Your paintings often seem to hover between control and openness. How do you navigate uncertainty in the studio, and what role does risk or not-knowing play in your practice?

In my everyday life, I am quite risk-averse. I like predictability, systems, and things that hold. The studio is where those flips. Painting is the one place where I allow myself to push something toward destruction without knowing what it’s for or where it’s going. I can begin without an end in mind, moving by rhythm and improvisation rather than plan, letting the body lead before the mind steps in. At that stage, the work feels loose and almost reckless, as if I’m testing how far the paint can go before it collapses. Then I swing back the other way. I circle the canvas, slow things down, start trying to organise what’s there, to make sense of the mess I’ve just made. I look for structure, for something I can stabilise or hold onto. And just as that begins to feel convincing, I bury it again. I disrupt the form I’ve just defined, covering it, pressing into it, letting it sink back into paint. The process becomes a kind of seesaw between order and chaos, between building and undoing. That tension feels bodily to me. There is a desire to control, to fix, to discipline the unruly, but there is also the body’s insistence on surviving on its own terms. Painting becomes the illusion that I can win that negotiation. That I can solve it, conclude it, bring it into balance. For a moment, the painting agrees. Then a fresh canvas reminds me that nothing has been resolved at all. The negotiation begins again, and that is where the work lives.

What does an ideal studio day look like for you? Are there particular routines or conditions that support your way of working?

It begins long before I arrive there. I need the morning to ease myself into my body rather than rush toward productivity. I walk my dog in the forest, let my thoughts loosen, write a little, move. By the time I eat lunch, I want to feel grounded and satiated. I have learned that I work best when I am not hungry, when the body is calm enough to take risks. After that, I can enter a deep focus that carries me through the afternoon. Entering the studio feels like entering a painting. Once I cross that threshold, time changes. I work until I am emptied, until the concentration gives way to exhaustion, and then I leave. I do not try to stretch past that point. The rhythm matters more than the hours. I am very led by the senses. I collect teas, perfumes, and small atmospheric cues that help me shift states. Smell, temperature, and sound all act as quiet guides, helping me tune the space so it can hold the kind of attention I need. When everything aligns, the studio stops feeling like a room and becomes a container I can step inside, one that receives the work and whatever needs to surface that day.

Bunny Hennessey – www.bunnyhennessey.com, www.instagram.com/bunnyhennessey

Born in 1991, Bunny Hennessey grew up in coastal Devonshire. She is currently in the final year of an MFA at Slade School of Fine Art, following an undergraduate degree at City & Guilds of London Art School, where she received First Class Honours. In 2024, she was awarded the Freeland’s Painting Prize. Her work has been shown at Chilli Art Projects, London, in a duo exhibition „Constrain“, as well as through Roamer Project II, where she was selected for the Val d’Aran edition of the group show in the Pyrenees.