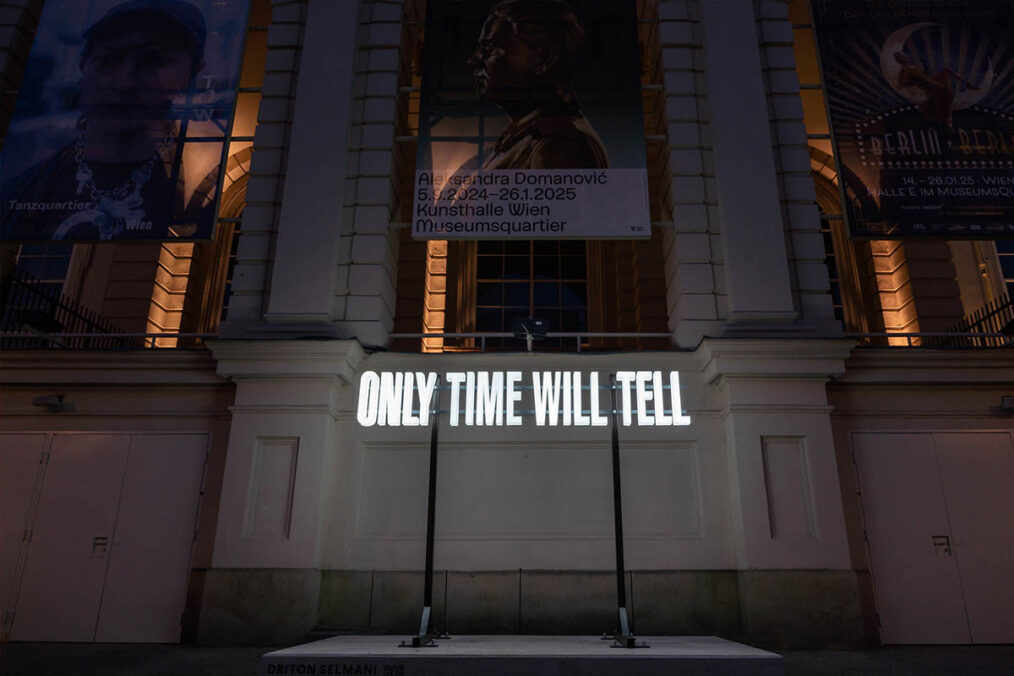

Although he had the possibility to live abroad, Selmani, after his MFA in Bournemouth, chose to return and work in Kosovo, a place often seen as peripheral, yet one that constantly feeds his practice with the tensions of fragmentation, memory, and resilience. This country, this „remote“ place (see Selmani, 2025), and the studio remain the sites where his artistic thinking unfolds. Following his solo exhibition at Kahan Art Space in 2023 and the public installation Only Time Will Tell at MuseumsQuartier Vienna, Selmani’s work is presented at viennacontemporary art fair this year by Gallery Ernst Hilger, a pick made by Ernst Hilger (28 February 1950 in Vienna; † 26 May 2025), before his passing. His new works engage with the cultural heritage of Vienna, the longevity of storytelling by superposing eras, references, and occurrences. The artist’s work is featured in Zone 1, a curated section spotlighting artists under 40, alongside Hélène Fauquet, Fabian Reetz, Melanie Ebenhoch, and Huda Takriti.

Erka Shalari: This year, you present your work with Gallery Ernst Hilger at viennacontemporary, where they dedicate a solo booth to your artistic position. How did the gallery first come across your work? At the same time, you are part of the fair’s curated section, Zone 1, invited by curator Aliaksei Barysionak. How does it feel to have your work placed both in a solo gallery presentation and within this very interesting curated framework?

Driton Selmani: The process began with a remarkable conversation I had with Ernst and Karoline, just weeks before his passing. The Gallery first encountered my work during Manifesta 14 in Prishtina in 2022, and since then, we have been in dialogue about a possible collaboration. Ernst’s profound knowledge of Central and Eastern Europe made it clear to me that “no” was never an option for them. I felt deeply honored to be considered, especially by someone who had spent his life building cultural bridges across this region. Aliaksei then became the final, and perhaps most important, piece of this puzzle. We first met in 2015 at the Chto Delat / Rosa Luxemburg School of Engaged Art in Berlin, and our paths have remained connected ever since. There is a shared “stereotype” between us: we both come from “the other side.” I find it meaningful, even poetic, that this background now frames our collaboration here in Vienna, a city that historically has been both a border and an epicenter, and now becomes the stage where these trajectories meet again.

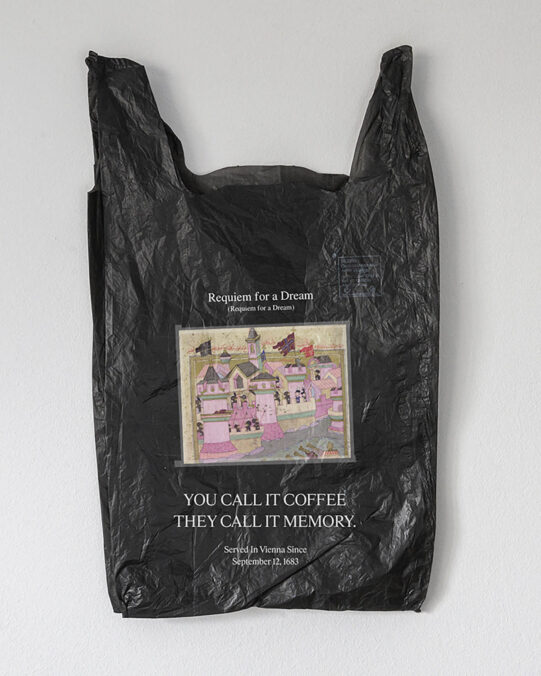

ESH: In the curatorial statement, Barysionak states that Zone 1 stands at the intersection of the political and the aesthetic, and looks at the conditions we bear in a moment of planetary emergency. How does your work Requiem for a Dream. Love Letters from the Siege connect to this idea?

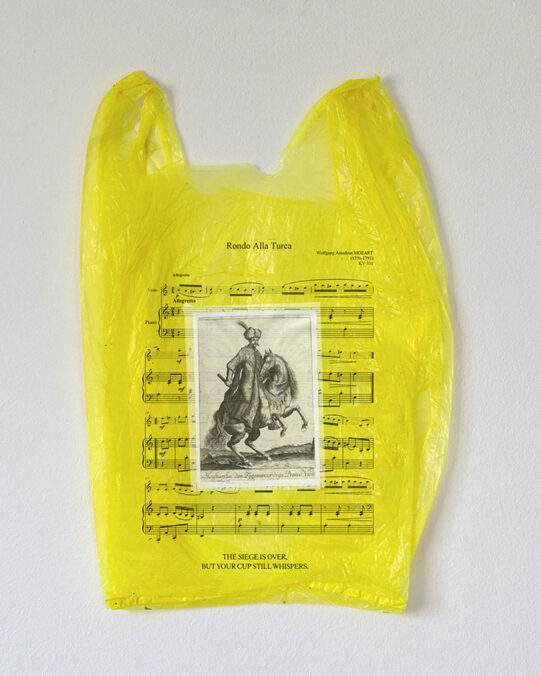

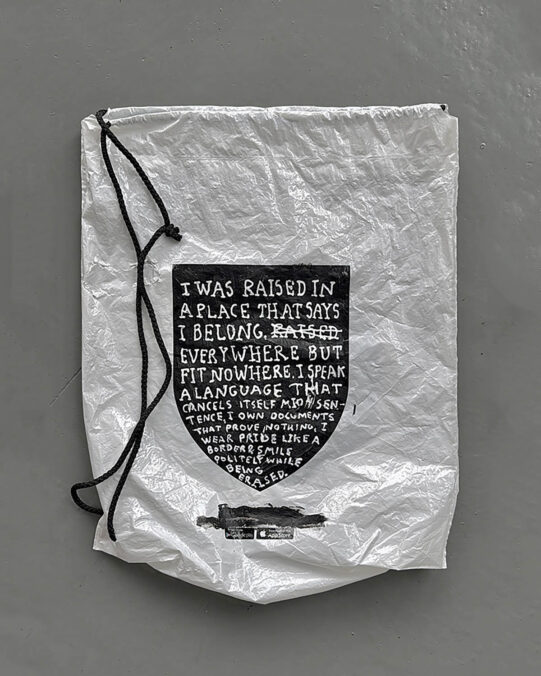

DS: The placement of my works makes me privileged, because in fact I come from a world badly entangled with politics, where there is little or no place for aesthetics, except for what would be the aesthetics of politics. Returning to Aleksei Barysionak’s curatorial concept: “Plastic bags deliver unexpected truths.” I embarked on an even deeper investigation, merging memory, displacement, and power; an attempt to rediscover what has been distorted on all sides since the Siege of Vienna until today. Requiem for a Dream covers the available surface of the plastic bag with centuries of historical remnants: a miniature painting of the Siege, a musical score of Mozart’s Rondo alla Turca, and miniature illustrations of the Ottoman chivalry period. These deceptively ornamental images are treated not as historical documents but as emotional debris; trace elements of a cultural moment that still permeate the contemporary European psyche. Each bag carries phrases that wound as much as they console: “You call it coffee. They call it memory.”, “The siege is over. But your cup still whispers.” They speak of empires not in grand narratives but in aftertastes and acoustic residue. In Vienna, where coffeehouses are romanticized as cradles of modern thought, the Ottoman origins of the brew are rarely mentioned. Here, I flip the filter: what arrives in the porcelain cup is not just coffee, but a history of conquest, exile, and mimicry. What Mozart turned into playful ornament with his Alla Turca, I reclaim with irony and grief.

My plastic love letters do not glorify the past but complicate it, suspending time between cultural digestion and erasure, between memory and commodity. These works ask: how do we archive affection in an empire that dissolves into Wiener Melange? How do we hold onto a feeling when history has already been packaged, priced, and served? The plastic bag, durable, ignored, and global, is transformed here into a document of intimacy and inheritance. Through this material, I write what official histories omit: the small, absurd, and beautifully persistent ways we carry each other, through sieges, through music, through coffee, through time.

ESH: The letters also feel like fragments of political memory.

DS: Letter No. 1683 and Letter No. 1684 are not simply notes, but fragments of a love affair between power and forgetting. Folded into plastic, they rustle like empires that never collapse, only change costume. Political ghosts disguised as everyday gestures, they remind us that history never ends, it just keeps leaking into our rituals.

ESH: Yll Rugova and Fanny-Alma Serée have described your practice as one of “superposing”, layering sources, eras, places, fictions, and facts — like anchoring pressing contemporary issues to deep currents of history, as in ZigZag. The new works feel just as alive in this layering. How has this art of superposing evolved for you?

DS: The method of superposing really emerged from my way of navigating memory, not as a straight line, but as fragments that insist on coming back. For me, history never stays where it “belongs.” It leaks, it reappears in unexpected objects, it becomes kitsch, it becomes personal. The plastic bag, the Ottoman miniature, the Mozart score, they are all debris that carries emotional charge and continues to shape the present. In a way, I follow something close to Walter Benjamin’s idea of “constellations,” where fragments from different times, once placed together, reveal a truth that was invisible before. Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas is also a key reference for me; the way he placed images from distant eras side by side, allowing cultural memory to flash across time, is not unlike how I work with sources, sieges, and aftertastes of empire.

Meanwhile, Hal Foster described this as the “archival impulse” in contemporary art: artists collecting and reassembling remnants not to glorify the past, but to expose what official archives omit. I think this is very close to what I do in Requiem for a Dream. Love Letters from the Siege: the Ottoman coffee cup, the Mozart score, the clichés of empire. I place them together not to tell history, but to ask how history survives inside our daily rituals. So the research is never about digging for a single truth. It is more like tracing how different times overlap, how an empire dissolves into coffee grounds, how memory is carried in the most banal, overlooked materials. Coming from a fragmented country like Kosovo, this method also mirrors my own reality: a place where even we ourselves often struggle to grasp the intricacies of what should be simple. Self-determination, as Machiavellian as it is utopian, remains a word that promises clarity while delivering endless ambiguity.

ESH: Back in our August call, we spoke about your work Der Ernst, Der Zeit. I’d love to pick up from there.

DS: Ernst and Karoline first saw my work in 2022 at Manifesta 14 in Prishtina, yet we never actually met in person. The plan was for them to visit my studio in Prishtina this summer, but time had its own plans: Ernst passed away only weeks before their visit. At that exact moment, I was on holiday in southern Albania. Out of a mixture of pride and naivety, I went swimming with a watch I really loved. The sea was violent that day, and the watch was torn from my wrist. Four days later, I found it again, broken into pieces, half corroded by salt. The irony is that it was a diving watch. This coincidence stayed with me. As Ernst’s time stopped, I was confronted with my own broken timepiece, and I reflected on the sincerity of time itself, how it can be playful, cruel, and indifferent all at once. It reminded me of Ahmed Imamović’s short film 10 Minutes (2002), which contrasts a tourist’s brief pause in Rome with a life destroyed in Sarajevo during the same ten minutes. From this came Der Ernst, Der Zeit, which is both an altar and a memorial. It is dedicated to Ernst, but also to the non-seriousness (Nicht Ernsthaftigkeit) of time itself, which shatters us, like the waves of the Ionian Sea, into fragments of memory and loss. A reminder that time is never owned, only borrowed; that even a watch cannot measure it, only betray it; and that what remains, in the end, is not the keeping of hours, but the breaking of them.

ESH: Many have remarked that you carry weighty ideas through the lightness of plastic. How did your fascination with plastic bags begin, and what does it mean for you to give agency to this material?

DS: Gjergj Kastrioti once declared: “I did not bring you freedom, I found it among you.” I always say the opposite: I didn’t bring you the bags, I found them among you! The idea of buying a canvas to paint on felt absurd to me. Instead, in 2018, I turned to the most common object scattered across the streets of Prishtina: the plastic bag. I fixed it, claimed it, fastened my thoughts to it, and let them soar like a feral animal, offspring of our own cruelty toward nature. I have always been drawn to the fragile borders of what is considered proper or improper in art. For me, banality is a value in itself. To work with it is both a counterattack against what cannot be avoided and a silent legacy: an affair with the readymade, neither forbidden nor downloaded, but simply present, insisting. Plastic, in this sense, is more than material. It is the residue of our time, the fossil of our present. As Bruno Latour reminds us, the planetary emergency shows that we are never outside nature, but entangled in the very crises we create. To write on a plastic bag is to admit this entanglement, where intimacy and catastrophe share the same fragile surface.

ESH: Your love letters belong to Atlas, a larger body of work, a kind of map beyond borders and nationalities. How does Atlas hold these various works together?

DS: As every atlas is a collection of maps, all collections of my bags also form a story for me and others. They are like maps of unofficial histories, fragile cartographies of moments that only reveal their meaning when placed side by side. Each bag becomes a page in an atlas of what is often left out, a record of the overlooked, of things carried but rarely remembered. Atlas gathers these fragments into one field: an accumulation of traces, small testimonies of time, love, and loss. One day, they may appear completely nonsensical, like so many other human discoveries that history has mocked, forgotten, or misunderstood. What matters to me is not their durability but their constellation, the way they chart a terrain of memory, intimacy, and absurdity.

ESH: Public space has been a vital field for your interventions since early in your career, with For God’s Sake (2008) marking your first work in this context. What does public space represent for you as an artist, Driton?”

DS: In 2008, eager to say something in a place with little room for expression, I turned to public space. By colliding truths and ironies, it became my paradise, especially in those sites where cultural hegemonies clash, where dominant narratives are reinforced but counter-narratives can still emerge. For me, public space is never neutral. To work there is to insist on visibility, to interrupt, disturb, or gently displace the everyday consensus. From For God’s Sake (2008) to Red Tape (2018) and Wanderlust (2016), my interventions seek to charge ordinary places with extraordinary memory, transforming a street into a stage, a wall into a question, a life vest into an archive of absence and presence. These are small acts of resistance: fragile attempts to claim space for what is excluded, silenced, or dismissed as banal. Public space is not a backdrop but a condition, where art negotiates its meaning, where intimacy becomes visible, and where the absurd suddenly appears as necessary.

ESH: Can you expand on your installation in Vienna, “Only Time Will Tell”?

DS: “Only Time Will Tell” isn’t just the title of the installation; it’s a kind of cheeky prophecy stitched into the main courtyard at MQ. In luminous letters, it stands like a weathered lighthouse, calling us not to wait passively but to step into the moment and help steer what’s next. The Installation in MQ’s courtyard, time becomes a mirror. Artists are not fortune tellers, yet we are constantly asked to say what the future will bring. That paradox runs through the work itself: it does not predict, it reflects. The courtyard of MQ is vast and ceremonial, a stage where thousands pass daily, yet the work feels personal, more like a pebble dropped in a pond that ripples inward rather than outward. For me, time has always been a construct of imagination, not a straight line but a cycle of fragments we hold until they dissolve. That idea echoed beautifully in this public space. That idea found a precise resonance in this public space. The work isn’t static; it asks you to pause, to reflect on what persists and what disappears. Positioned by curator Verena Kaspar-Eisert so it’s impossible to ignore, the phrase hovers above your head as you move through MQ, not a piece you walk past, but one that walks with you long after you’ve left.

ESH: I often follow your drawing interventions you do on IG stories. They are same time concrete and fleeting. Do you see them as sketches, or could they stand as premonitions in their own right?

DS: They are an unstoppable ritual, somewhere between meditation, the boredom of existing, and the utopias that arrive right after an espresso. Honestly, they are a mixture of everything. I don’t even know myself. Maybe sketches, maybe warnings, maybe just doodles against oblivion. But somehow they feel like a necessity, as if without them nothing else would make sense. Or at least my coffee wouldn’t. Drawing, in this sense, becomes crucial; it gives a body to ideas that would otherwise stay invisible. And those half-baked scribbles, however fragile, are apparently what keep the world spinning, or at least what keeps me from falling off it.

ESH: I am curious about your studio rhythm. What does a week in your practice usually look like?

DS: My studio rhythm is very professional: three days of procrastination, two days of panic, one day of productivity, and half a day of cleaning up the mess so it looks like I knew what I was doing all along. A week in the studio usually looks like this: I make coffee, look at the same object for hours, convince myself it’s brilliant, then decide it’s terrible, and finally pretend that the whole process was intentional. Somewhere in between, something actually gets finished.

ESH: And how do studio visits feel for you?

DS: Studio visits feel like waiting for ships that may or may not arrive. Being here, I often feel detached from the art world, like an islander staring at the horizon for sails that never quite appear. History is full of such remote places, people on forgotten islands waiting months or even years for a ship to bring news, salt, or a letter that might already be outdated by the time it arrived. Artists live in a similar Beckettian condition of expectation. The visit already feels too late before it even begins; time has passed, and yet the long process of waiting, rehearsing, and repeating continues. The visit becomes less about what is shown and more about the theatre of waiting itself: closer to Waiting for Godot than to any practical exchange. Perhaps this is why I sometimes think of my studio as a shore, and each work as a message in a bottle, cast out into uncertain waters, unsure of when or where it will wash up, or who might uncork it. What arrives is rarely what was expected, and often the only thing that arrives is the waiting itself.

Curated Zone 1 / Booth C23 | viennacontemporary 2025, Messe Wien Halle D | 11 – 14 September

Address and Contact:

Gallery Ernst Hilger

Dorotheergasse 5/3a, 1010 Wien

www.hilger.at

Driton Selmani – www.dritonselmani.com