She takes a lot of pictures and stares at them at night.

I met Beate Frommelt more than ten years ago in a gathering of artist residents in Berlin. She wore a far too big camel beige coat and smiled at me. I met her again and again, visiting her openings and talking with her about our works and everything. By curating a short retrospective* of her work on Instagram we thought to publish some of our private talks and to transform them into this interview.

Sibylle Ciarloni: Which route do you take the most at the moment?

Beate Frommelt: The green border between Austria and Liechtenstein.

Beate Frommelt, AIR Klostergarten Mariaberg, Case Study, View

You often work site-specific. What are your rituals or gestures to get in touch with a landscape, place, or space?

I spend a lot of time in the space. Walking around, sitting, observing the light during the day, how and if people move through the space, how they use it, are there other creatures living in it like animals and plants or maybe ghosts. I take a lot of pictures and stare at them at night.

Is there a space you dream of working with?

There is no specific space. Hidden stories and myths can be discovered in any corner, sometimes the most ordinary can reveal the most fascinating.

You recently worked with two other artists (Asi Föcker and Claudia Marolf) in a Residency at Kloster Mariaberg in Rorschach. The garden is inspired by the via crucis. How did you find your own path in this heavily geometrical landscape?

Our western landscapes are functional and organised according to economic patterns. The churches, too, have laid out their gardens in such a way that free wandering is out of the question. But there is a longing for wild nature. I have been researching the subject for years. In my artist residency at the Mariaberg monastery, together with Asi Foecker and Claudia Marolf I sent a few boxwood bushes on short cuts.

In my research I realized that the rigid geometrical design of the medieval garden is created like this to give structure to the ritual movements of the inhabitants of the monastery. In Mariaberg I observed, how students are now using the paths through the garden and was amused by the development of short cuts (Trampelpfade).

It seems to me, that you are observing the fight between nature and artificial landscape. What is fascinating you?

Very little of what we see as nature is actually untouched or uncultivated. One has to go to really remote places to experience landscape that is not somehow touched be civilization. I am mostly interested in the friction that exists between our longing for untouched nature and landscape and what really exists around us.

If you go thru your working processes, which were the best experiences and why?

I try not to think about the result too much. I start observing, researching, reading, collecting and playing with my findings and in the best scenario the work evolves out of this process naturally. I often start drawing, but the use of material or media in the final execution is often a result of my research (fabrics I found in the archives, etc.). The best moments for me are when the result is a discovery, something unexpected.

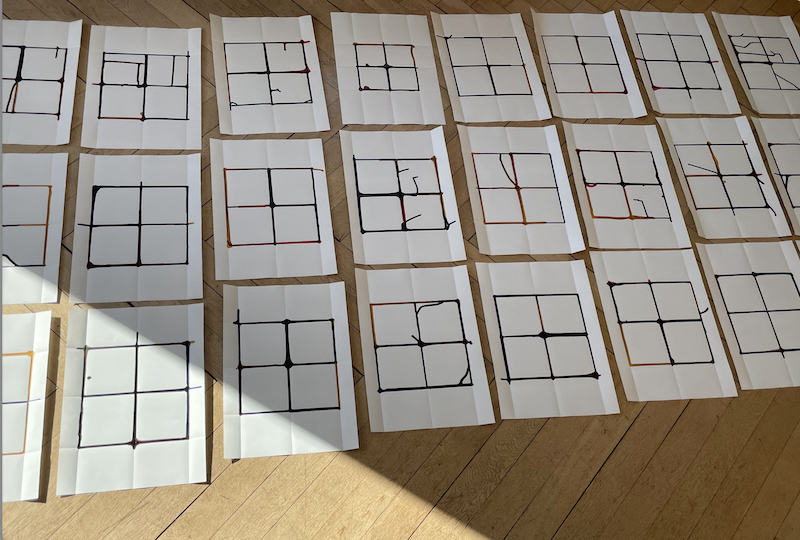

Beate Frommelt, Via Crucis, drawings, ink on paper, 2022

In your works, you often repeat but never get the same sign; it‘s just the same gesture. What is it about?

Repeating a gesture, especially a drawing gesture is kind of a play or meditation to get into working mode. I like to draw, it helps me think. I use geometrical forms because I don’t want the form to really matter. I am interested in the moment where „mistakes“ or small deviations appear in the repetition. I allow them to happen and am curious of the new path that is developing out of this process.

The work starts with rigid structures or forms, but since drawing is also a physical act and the body is involved, this deviations are likely to happen. Maybe the rebellious act is provoking the deviation. It is mainly about trusting the process and the shapes that are resulting out of this process.

Beate Frommelt, Zaungast, Installation View, Schaan, 2019

You have an archive with works or parts of it. I sometimes wonder what artists, who produce things, do with them after an exhibition. What do you do?

I sell works to private collectors and institutional collections. Since the works are mostly site specific I try to find buyers that have a relation to the space (f.e. community archives, specific foundations, etc.). I don’t work with a Gallery anymore, I like to be totally free in what I am producing. The other works live in my studio. Sometimes they get reworked. Sometimes they get recycled or included in new projects. I prefer to work with materials that are variable in their use and change their shape. Like thread, which is almost a material of pure potential, it only gains shape or body in the way you use it. It can define a space, be architectural, have presence and then disappear again.

Beate Frommelt, Eine Linie wandernd, Installation View Flutgraben Berlin, 2012

Besides your career as an artist, you are a teacher to young people at art school. Which are the first things you say to them?

Keep asking questions and honour the process. Don’t trust too much in styles and appearance of the work. Don’t think too much about the outcome, keep working.

You have recently been to Indonesia as an artist and co-curator. What did you bring back? Tell me more please.

I brought back a lot of precious memories from this journey. So many encounters with people that opened my horizon and filled my heart with love and appreciation. I experienced a strong sense of community in the Indonesian art scene. There are a lot of art collectives with members of all professions. The willing- and naturalness to co-work, co-live, co-create, discuss ideas, support each other and share left a deep impression on me.

Do you read books and if yes why?

I love reading. I often think in images, reading helps me put words to what I am doing and organizes my thoughts. I start reading a book, in the middle of it a new one comes along, that catches my interest. I always carry a couple of books around until I finish them. At the moment: Wurzelstudien by Anna Ospelt, All about Love by Bell Hooks, and Der symbiotische Planet by Linn Margulis.

What is your actual most loved song, and why?

It is Gil Scott-Heron’s „Me and The Devil „. The song’s atmosphere and beat are hypnotic and keep me going.

Is music helping you work, or do you need silence?

It really depends on the work phase I am in. Sometimes I need silence in order not to be influenced or distracted. Sometimes I enjoy music, mostly when I am already in production mode and don’t have to take many decisions anymore.

interview-beate-frommelt

Before we get to the very last question, please answer these associative or-questions: Morning or tree? Always a tree. Garden or pasta? Eating pasta in the garden? Love letter or water? Let love run through you like water. Snow or dancing? Can’t decide on this one, love them both.

Beate Frommelt, work in progress, sugar and paraffin wax

Beate Frommelt, Piz Zücher, Installation View / Walk-in Picture, Pontresina, 2017

Your materials beside drawing are also paintings and installations with thread. And you worked with sugar. Tell me more about your work with the sugar loafs you made for a walk-in picture in Pontresina 2017.

Randulinas is the raetho-romanic word for swallow. Swiss migrants who left their place in southern-east Switzerland were called Randulinas. They worked abroad and some of them were estimated as confectioners. Two times I worked with sugar until now. Once for an installation of sugar loafs as a walk-in picture and once for works on paper combining sugar and colour sediments.

Randulinas is the raetho-romanic word for swallow. Swiss migrants who left their place in southern-east Switzerland were called Randulinas. They worked abroad and some of them were estimated as confectioners.

Can you tell me something about a further project and research?

I am currently working on a series of glass panels, that will be used for a mortuary. It’s an architectural project. Through the use of the so-called moirée effect, the spectator finishes the image in his brain. It also changes its perception depending on the position or perspective of the viewer.

Interview Beate Frommelt

*

Retrospective

10.-15.7.2023

on Instagram

Beate Frommelt works site-specific in collaboration with what and whom she is surrounded by. With her love for narration, she watches out for hidden stories behind wanted forms and behaviour. Beate Frommelt lives and works in Zurich, MA Fine Arts, Universities of the Arts, Central Saint Martins, London. MA Art Education, Zurich University of the Arts. Exhibition Activity in Switzerland and abroad. All pictures courtesy & copyright Beate Frommelt – www.instagram.com/the_real_beatle/, www.beatefrommelt.ch

Sibylle Ciarloni, writer artist curator based in San Costanzo. She deals with long-term wor(l)dbuilding, with the voice of things and collaborative thinking. And sometimes she walks her dog on the beach really early in the morning – www.instagram.com/rumore_24, www.sibylleciarloni.com