Julia, as a curator of the exhibition, how do you see the relationship between the body, materiality, philosophy, fiction, and technology in Thomas’s work? How political do you think it is?

Julia: I see a very clear political aspect in Thomas’s work. For me, his entire practice is about how politics are shaped. But it’s not about politics in a superficial or current-events sense—it’s not about reacting to daily news cycles. It’s more fundamental in the case of his work. This is something I also see in relation to the Vienna Actionists. They weren’t activists, but they created situations that invited reflection; they challenged the viewer to reconsider structures of power and the body. That is very important to me, also in my role as the director of this museum. I see it as essential to show contemporary artists like Thomas in dialogue with the Vienna Actionists. Even if, on the surface, it seems there’s no direct connection, there is a deeper one. And once you begin to understand that, new perspectives open up.

Thomas: One work from the DAIMON series is on view in my solo exhibition at WAM; the piece belongs to a constellation of works that examine invisible forces. This brings us into the realm of demonology. In ancient Greek philosophy, for example, „demos“ in democracy comes from „people,“ yes—but there’s also the deeper root „daí,“ which connects to daimon, or spirit. That word, daimon, means something like the allocation of rights, energy, and resources—both physical and metaphysical. And isn’t that exactly the fundamental question of democracy and our society today? Who has access to air, water, electricity, or even joy or humor? Allocation, especially in the context of technology, is interestingly from the 1920s through the 1960s, in technological thinking, the term “daemon” was often used to describe hidden processes—those running in the background of computer systems, invisible to the user but making crucial decisions. Even in UNIX systems, you have daemons that control processes silently, in the background. So in a way, artificial intelligence, too, is part of this long tradition.

I’d also like to ask about the part of the installation DAIMON 2007 that is exhibited; at first look, it reminded me a little of a DJ setup. With the cables and connections, but then it also started to feel more like a kind of vintage synthesizer from the 1970s. At the same time, I had this strong association with a data center or server room, some kind of infrastructure like the ones Meta and Facebook operate in remote places, for example. It gave the impression that there’s something invisible flowing through this installation, some kind of data or energy being transmitted. Can you talk more about that?

Thomas: That’s very much in line with what I intended. One familiar example of Daimon is the “Mail Delivery Daemon”—you get messages from it when an email fails to send. So, these hidden processes that keep systems running in the background—that’s what I wanted to reference. And the idea goes even further back. In the early days of thinking about artificial intelligence, in the 1950s, there was a concept called the Pandemonium Architecture, developed by Oliver Selfridge. It was just a thought model, not real software at the time, but the idea was to imagine a network of little “demons” working together—each performing a specific task. Together, they would create something resembling intelligence. He even called it “artificial diligence”—a play on artificial intelligence. Back then, it was pure theory, but today it’s become part of our reality.

Thomas’s oeuvre spans over more than thirty years. How was it for you to select the works that will be on view at WAM, and how was this relation to the Vienna Actionism movement highlighted in the process?

Julia: Thomas initially made a pre-selection of the works, which became the starting point for my deeper engagement. As I began writing and researching the material, one work especially came to my attention. One of the central works, BIOPHILY (1993–2002), involved a symbolic marriage of artist to a rubber plant in India and a transgenic experiment in which gold-coated DNA was injected into the plant’s cells, The project, realized in collaboration with an assistant at a Swiss university institute, was discontinued by the head of the institute in the run-up to the Swiss gene referendum, carried out in April 1997. The plants had to be destroyed, and a publication of the results was prohibited. This bio artwork then became a base for the whole collaboration and exhibition.

Thomas, there is a big aspect of your work that is based on fictional, philosophical, and mythological elements. Can you elaborate on this layer of your work?

Thomas: All my projects have three levels. So, first we all know is a very traditional level dealing with images and objects, cultures, drawings, and so on. And then secondly, a very important level, which is dealing with matter and materials, also with bio processes and molecules. And this level is also based on the research and mostly incorporation scientists, microbiologists, and software engineers, collaborations with departments of medical universities or universities of biology, depending on the type of the project. And there is a third level, and this is the layer of language. This level is also related to literature, especially speculative fiction and science fiction. Based on these concepts, I’m doing speculations and transferring them into art. I do speculation in the context of information, technology, and biotechnology, on how this transforms human beings, daily life, life conditions, and so on.

Let’s say that the visitor of the exhibition didn’t read the text that describes the work and the concept behind it. How open are you to the visitor having their own interpretation?

Thomas: This format of exhibition is quite unusual for me. The works shown here span the last thirty years. In most of my exhibitions, there’s a strong emphasis on material interconnection—sculptures, objects, apparatuses, and machines that are not only conceptually but often technically linked and connected. For example, in many projects, the starting point was photosynthesis. We used it to generate specific biological materials—what I call “materials” in an expanded sense—because each cell behaves like a factory, producing fatty acids, proteins, carbon structures, and more. These substances are then transformed in subsequent steps, triggering new processes and forming the next chapter of the exhibition. As a visitor, you might first see a plant-based process, then observe how it evolves into a sculptural object, and later into another system or installation. Occasionally, the cycle even returns to its beginning.

I’m also hesitant to use the term “visual art,” because it suggests something seen. I prefer the German term “Bildende Kunst”, which implies an active shaping or forming of material. For me, that’s much closer to what I do: I work directly with matter—with molecules, materials, and processes. As a sculptor, I don’t just describe reality—I intervene in it; I do something with it. I built something that exists physically, in the real world.

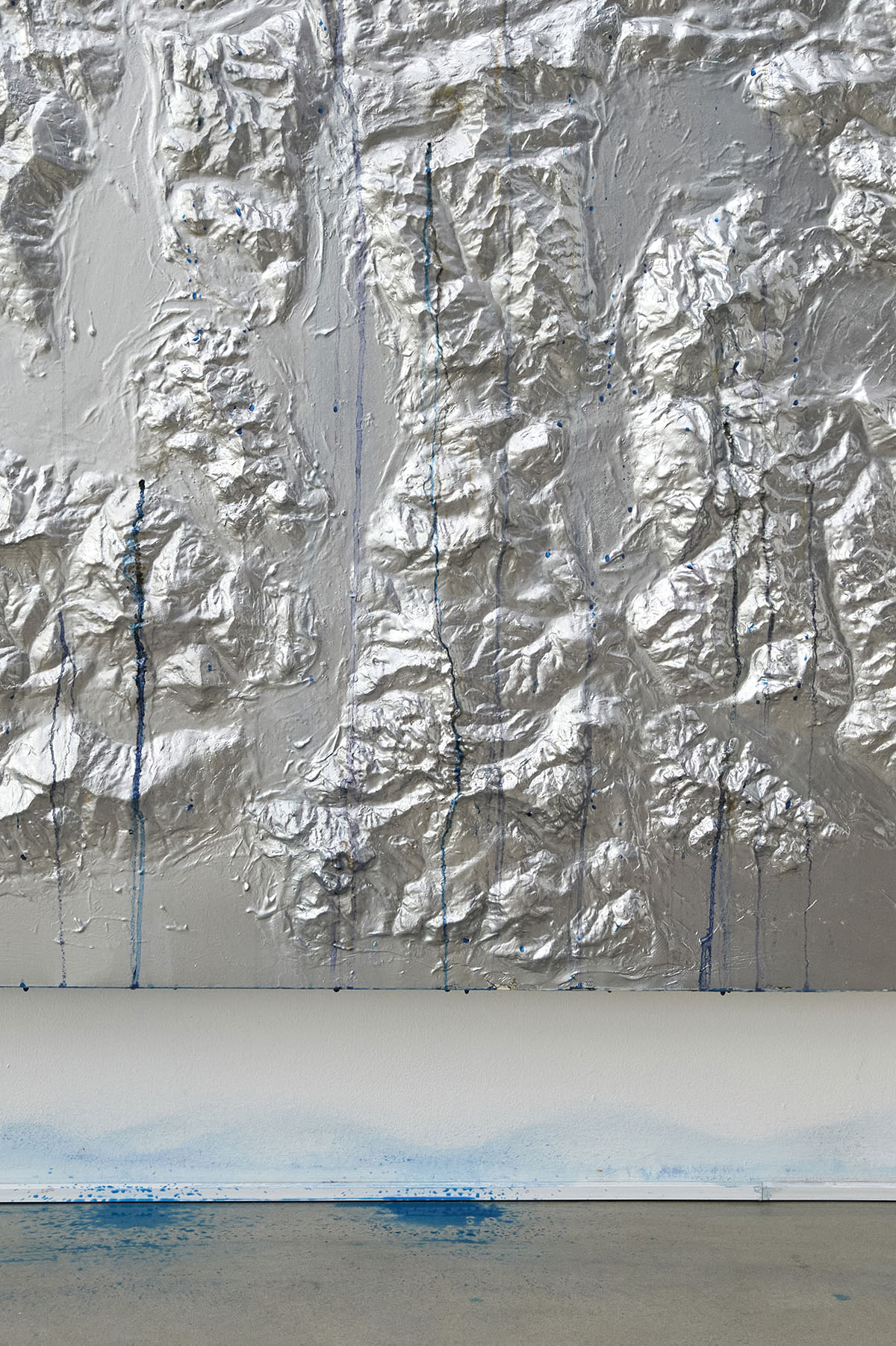

My work relates deeply to ecological and environmental questions—topics we’re all engaging with daily. But I’m not interested in illustrating catastrophe. I don’t want to show burning forests or melting icebergs. That approach reminds me of 19th-century painting—depicting something from a distance, representing a problem rather than working within it. What interests me is offering tangible, real-world processes that could evolve and change.

We’ve spoken about how your work often includes references to plants, animals like the octopus, and even machines. These aren’t just random choices. So, how do you see the symbolic meaning of these elements?

Thomas: Each figure, whether it’s an animal, plant, or machine, carries a certain symbolism or function. The octopus, for example, has many layers of meaning. Yes, it appears in ancient Greek mythology, but beyond that, its physical form fascinates me as a sculptor. The octopus doesn’t have a fixed shape; it’s fluid, constantly transforming. It can squeeze through tiny spaces, change color, and shift texture. In a way, it challenges the very idea of form. This reminds me of Robert Morris and his idea of anti-form, the notion that sculpture doesn’t have to be made from solid, classical materials like bronze, stone, or marble. Instead, it can be made from soft or changing materials like fabric, steam, or even gas. The octopus, in that sense, is a living form of anti-form.

Human bodies are symmetrical—we have left and right sides, structure, and a kind of balance. But the octopus disrupts that order. For many people, this is disturbing. But for a sculptor, it’s exciting. It opens up the idea of sculpture to something more biological, something that grows, transforms, and eventually decays. And that, to me, is closer to real life.

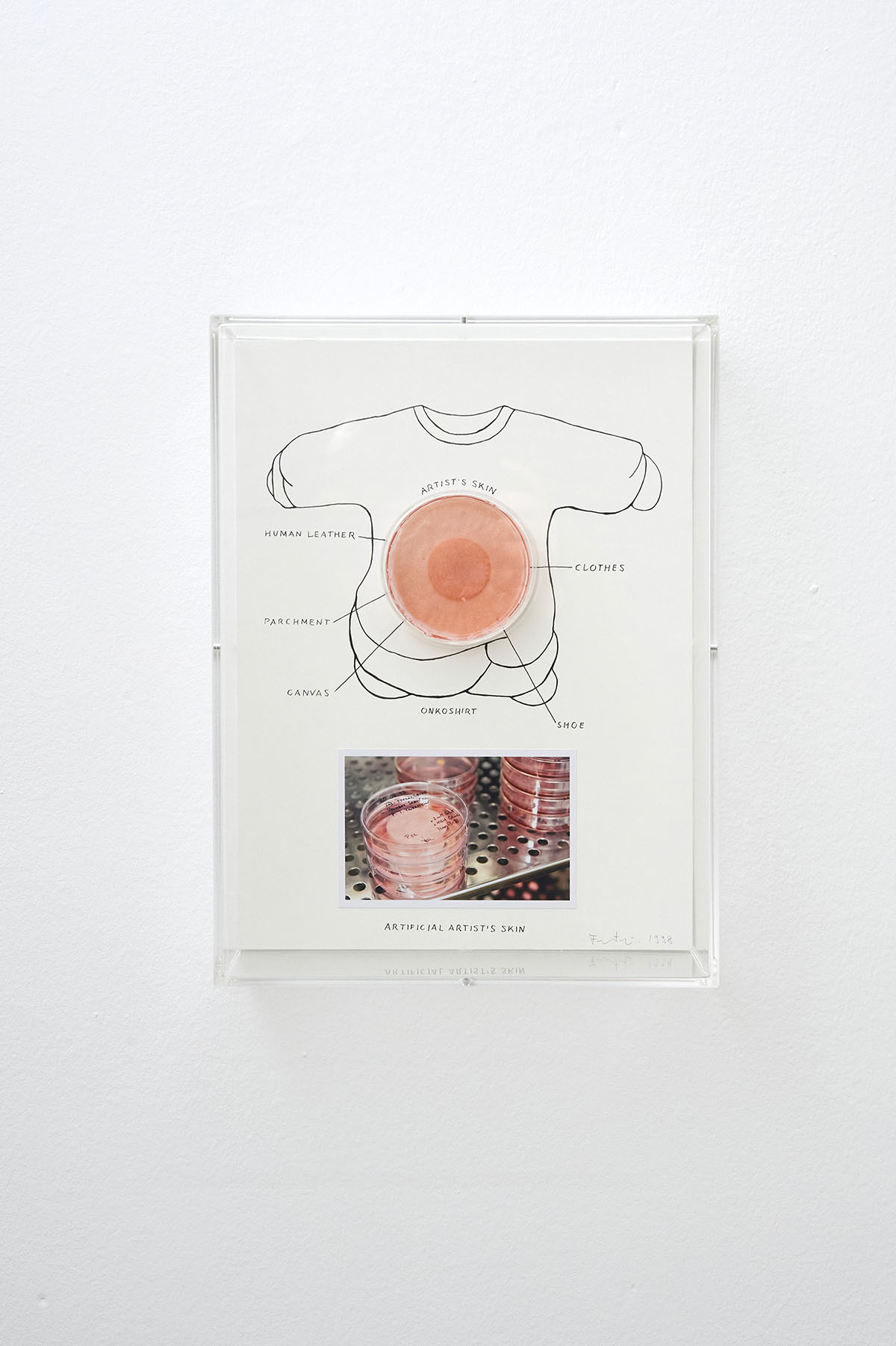

The materials you are working with are very different; they can be organic, synthetic, biological, and mechanical. You even worked with your cultivated skin cells for the work Onko-Shirt, 1998. Can you tell us more about that?

Thomas: The idea was: why rely on animal skin when I could use my own body to produce material? At the time, I was curious about how far one could go with the idea of self-production, quite literally producing from oneself. I took a few samples of my skin cells and cultivated them in a petri dish. The cells grew, but they formed a very thin, fragile layer. At the time, I was very naïve; I imagined I could use the cultivated skin like leather, tailor garments from it, or use it as a kind of pigment or paper for drawings, maybe even make shoes from it. So, it ended up as more of a conceptual work than a functional material. But still, I find it to be one of the most meaningful pieces.

Exhibition: Thomas Feuerstein – ARBEIT AM FLEISCH

Opening: 27 May 2025 at 06:00 PM

Duration: 28 May until 27 July 2025

Opening times: Wed-Fri: 1:00 PM—6:00 PM | Sat. Sun. and on Public Holidays 11:00 AM—6:00 PM

Address and contact:

The Vienna Actionism Museum (WAM)

Weihburggasse 26 1010 Vienna

www.wieneraktionismus.at

Curator Julia Moebus-Puck on the exhibition and the work of Thomas Feuerstein: Thomas Feuerstein is one of the most exciting and versatile artists of his generation. In his work, he combines art with science, literary history and philosophy – always with an eye on the boundaries of the body, identity and life. The exhibition ARBEIT AM FLEISCH provides a comprehensive insight into Feuerstein’s work: from early performances, drawings and photographs to expansive sculptures and installations. Drawing on the tradition of Viennese Actionism, Feuerstein addresses central themes such as physicality, transformation and the merging of art and life. The focus is particularly on the question of how our relationship to the body is changing in a world that is increasingly digital, technological and networked. Feuerstein’s works combine artistic radicalism with philosophical depth. They invite us to reflect on the human being in the 21st century – on the interplay between nature and technology, between body and machine.

Thomas Feuerstein (born 1968, Innsbruck) is an Austrian contemporary artist, he lives and works in Vienna. His works and projects are realized in different media. They include sculptures, installations, environments, objects, drawings, paintings, radio plays as well net art and BioArt. Feuerstein’s work is known for growth and transience, processes of transformation, biological metabolism and entropy. www.thomasfeuerstein.net