Erka Shalari: Even though I always read the bios of the people I interview, I would still like to pose this question: Claire, can you introduce yourself briefly?

Claire L. Evans: I’ll keep it simple: my name is Claire, and I’m a journalist, musician, and artist based in Los Angeles (smiles).

How did your interest in computers, technology, music, and biology first develop? How do the themes that shape your work usually come to you?

A big question. I think of myself primarily as a writer: I write music, I write songs, I write articles, I write all sorts of things. The practice is the same, it’s just different applications. I’ve always been interested in technology. My dad worked for a computer company, and I had a computer in my room when I was a little girl. It was a big part of my development as a person and as a writer, but I’m also quite critically-minded, so as I grew up, I became a science and technology journalist, looking at social and cultural aspects of technology. Which, in my mind, connects to my work in music and the arts, because, of course, we use technology to express ourselves. So all these things coalesce.

The outlier, I suppose, is my current interest in biology. After being a tech journalist for many years, I think I just got burned out. During the pandemic, like a lot of people, I turned towards the natural world. I realised that there’s so much about life that I don’t understand, and that science still doesn’t understand. I became interested in how we use technology to think about nature and how nature helps us think differently about technology. I found this to be a new way into subjects and themes that have always interested me. It felt more generative and interesting, and potentially hopeful, than writing about technology companies and hardware.

You’ve given many talks and participated in various festivals over the years. What do you find to be the most challenging aspect of speaking in these formats, and what is it that you always find rewarding about them? Is there, for example, stress before a public talk?

Well, writing is a very solitary pursuit. It’s a lot of time locked in a room, thinking and doing research. And once you finish, you don’t always get feedback from readers. If you’re lucky, people read your work and send you messages, or post about it online—but you don’t get to have much of a conversation about it. So I enjoy giving public talks. It’s a wonderful privilege to share things with people directly. It also helps me navigate my ideas, because sometimes, you know, when you say something out loud, it feels quite different from what it does on the page. And I’m always working towards communicating complex things as clearly as possible; in person, on a stage, with a limited amount of time, you have to be concise and clear. I find that helps my thinking.

I’m fairly accustomed to public speaking because of my other life as a musician; when I play shows, you know, I can see how the music affects people physically (smiles). But it is, of course, terrifying. I think I’m pretty good at it, but every time I go on stage I still think, „Oh my god, what am I going to say!” It’s nice when it’s over; you’ve accomplished something, you get feedback, and you can have a glass of champagne.

How did the invitation to Vienna Creative Days 2025 come about?

Like invitations always come, in my inbox (smiling). It came through a friend, who had seen me give a presentation in Copenhagen many years ago. He made the connection with Creative Days, and when the opportunity came, I said yes. I’ve never been to Vienna. The great thing about being an artist is that you can use your work as a ticket to see the world. I’m so lucky that people invite me to give talks like this; it allows me to see a new city, not just as a tourist, but as a part of a community of thought, which is the best way to see the world and to connect with people.

Can you tell us something about the talk?

I’ll be giving a high-level presentation about the field of research that I’ve been engaged with over the last five years, which sits at the intersection of computation and biology, looking at different ways in which living systems can inspire us to build better, more resilient, and more sustainable technologies. As humans, we think that we’re very clever because we can solve problems and build machines, but our machines and our solutions are expensive and energy-intensive, and they have many other costs. But nature is clever too. For example, the “algorithm” that Harvester ants use to forage for resources is essentially identical to the algorithm we use to organise how data is transferred over the internet. So ants solved the problem of building efficient networks millions and millions of years before we even thought about it. The natural world is full of these examples of living systems that can solve complex problems. And the more we understand about biology, the more we realise how capable it is. There is a sense that we will never be able to fully capture the complexity of everything going around us in nature, and that can be overwhelming, but it can also be humbling and inspiring. It puts a lot of things into perspective, like our obsession with artificial intelligence. We think that artificial intelligence is just around the corner, but we can barely create a computer model of a worm or an ant. It’s almost laughable. My presentation will look at specific organisms, like ants, and look at slime molds and forests, but it is also a kind of philosophical reframing of how we could move forward more sustainably with technology.

What else can AI learn from nature?

There is a lot to be learned from nature. One of the examples that I like to give is that when we design AI systems, we tend to think about modelling a human brain. AI models are built on this idea of an artificial neural network, a very simple imitation of how a brain works. But intelligence is much more than just the brain. Many organisms that have very simple brains, or no brains at all, can solve problems through other means. By directly interacting with the environment, with their bodies, with chemical signals, or through collective intelligence, like social insects

So, intelligence is not just about brains. It’s about brains and bodies, those bodies’ relationship to the world and to other organisms, too. Intelligence is a much more distributed thing. Our fixation on the human brain is egotistic.

You are working a lot with speculative fiction, you have, for example, co-edited Terraform, and I find it very inspiring. I wanted to know how Brian Merchant and you selected the contributing authors, and what kind of futures do these pieces point us toward?

The operating principle behind Terraform—a science fiction magazine that became a print anthology in 2022—is that we wanted to cultivate science fiction writers who directly engaged with present-day issues in technology, science, and society. Science fiction can sometimes be escapist, traveling to the distant future or fantastical worlds. But we were interested in finding writers who were exploring the present and the near future. As editors, what we did was identify contemporary issues and ask science fiction writers to extrapolate from them directly. For example, Uber has a new policy about X. Where will that go in five years? Or this new AI model has arrived—what will it be able to do in five years? Science fiction is a really important and useful tool for thinking critically about our world, and it helps us think about the consequences of our actions.

A lot of these stories tended to be quite dystopian—maybe because of the nature of the world. A lot of the stories we published are quite dark. They are about things like labour automation, climate change, political surveillance, and the metaverse supplanting reality. But I think, in a way, when you see these alternative futures, you can more clearly understand what is happening now…and what to do in the present to ensure a better future.

Anxiety, decay—is there hope for the future? I was also thinking of the YACHT song I Thought the Future Would Be Cooler. How do you see the future?

We are living in interesting times. And it’s easy to succumb to feelings of dystopia. But that’s why I’m so interested in biology. The living world gives us an example of what real resilience looks like. Plants, for example, they’re survivors. In every context, regardless of the conditions, they try to grow. They don’t always grow tall or healthy, but they don’t give up. The principle is to survive and to continue. That works in the long run. Look at any human-made environment that has been abandoned; the plants always take over. There is a real power in the stubbornness of life, its relentless drive to survive. Biology makes me hopeful. Whether or not we survive, they will. But also they can show us how to survive, how to be resilient, if we pay attention to them.

As for music, yes, it’s funny that “I Thought the Future Would be Cooler“ was written over ten years ago now.

At the time, I remember people saying it was too cynical, but I guess we’ve been vindicated (smiles); that song does still feel very relevant. But making music is a form of resilience, too.

If you could speak a bit also about the album that you mentioned in our last email, that YACHT released in 2019, where you were collaborating with several machine learning systems. Of course, it also ties with your interest in technology…

Every album we make is very different or employs a conceptual framework. The album you mention, Chain Tripping, came out in 2019, and it was a form of creative research—a way of teaching ourselves as much as we could about AI, through the process of making music. We started in 2017, using the best AI tools available at the time; it feels like a thousand years ago, in AI terms. But a lot of the tools that we take for granted now were being developed then. So we were able to explore early models for generating song lyrics, generating melodies, doing typography, album art, and videos. We were really trying to figure out how these tools would affect music-making in the future, but it was so early that it required an enormous amount of human intervention. That’s fortunate—I don’t think you can make any interesting art without plenty of human intervention.

I think it will be very interesting to look back on Chain Tripping in a few more years. Maybe it will feel archaic, but I’m proud that we figured out a way to be ourselves as part of that process. To still have our voice and point of view, even when we use these tools of automation. We had to make a lot of choices, which is what making art is all about—making choices.

It’s great to hear about how the process unfolded.

Yes, we learned the basics of AI. The album came out in 2019, and it was very difficult to talk about then, because the technological literacy around AI was still developing. People had a sense of what AI was, but they didn’t always understand the politics of it or how training data works. It was very difficult to talk about the process.

What’s YACHT up to these days?

We’re still making music and other related projects. YACHT has been working underground for over 4 years on a major project, which will come out mid-May, just after Vienna Creative Days, so our energy has been focused on this project. But we do music still, and we put out an album in a couple of years. We consider ourselves to be the world’s first “post-AI” band. Technology is interesting, but we’re far more more interested right now in making music for our friends using our bodies and minds (smiles).

Looking forward to seeing you in Vienna.

Creative Days Vienna 2025

14 & 15 May

Keynote Sessions at The Hoxton, Vienna (Auditorium)

14 May | 6:00 – 7:00 PM & 7:00 – 8:00 PM

The capacity is limited, and a separate ticket is required – here.

Explore the full program here: www.wirtschaftsagentur.at

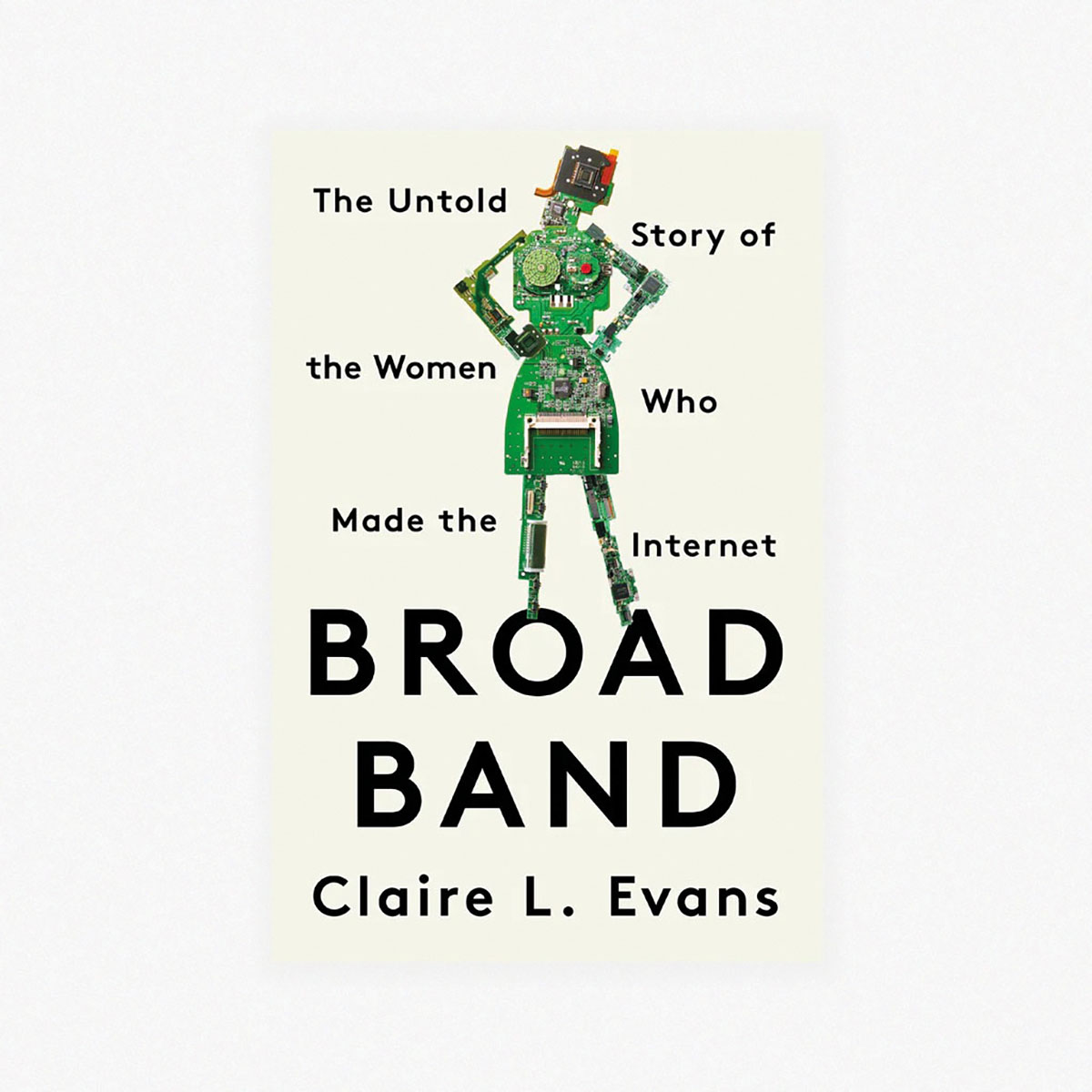

Claire L. Evans is a writer and musician exploring biology, technology, and culture. She is the singer of the Grammy-nominated pop group YACHT, co-founder of VICE’s imprint for speculative fiction, Terraform, and co-editor, with Brian Merchant, of the accompanying anthologyTerraform: Watch Worlds Burn (MCD Books, 2022). Her 2018 history of women in computing, Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet, published by Penguin Random House, has been translated into six languages and was named one of the Top 10 Best Nonfiction Tech Books of All Time in 2023. Her writing has appeared in MIT Technology Review, WIRED, The Verge, Pioneer Works’ Broadcast, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Document Journal, Eye on Design, The Believer, and Aeon, among others. Her 2022 profile of the lost hacker Susy Thunder was nominated for an ASME Award; a feature film adaptation of the story is currently in development at Paramount Pictures. She has given invited talks at the Hirshhorn Museum, Walker Art Center, TEDx, La Gaité Lyrique, Google I/O, The New Museum, XOXO Festival, MUTEK, Goethe Institut, Manchester International Festival, SXSW, Gray Area, Neural Information Processing Systems, the Association for Computational Linguistics, and the Decentralized Web Summit, among others. She is a 2024 MacDowell Calderwood Fellow for Journalism. She lives in Los Angeles, where she is an advisor to students in the Media Design Practices program at Art Center College of Design – www.clairelevans.com.