It’s so great to have you in Vienna again. I still remember your exhibition at Gallery Meyer Kainer in 2022, and now to see your work within the context of Franz-Josefs-Kai 3, it’s just great! How did the architecture, tradition, and history of the space at fjk3 influence, or not influence, ‘Orchestrion’?

I do a variety of things—painting, writing, and collaborating with many people on exhibitions; it’s a pretty heterogeneous mix in my practice. But nothing compares to the joy of working in a physical space. The more layered the space, whether physically or historically, the better. It activates the work in a very special way.

Now, this exhibition was originally conceived for Z33 in Hasselt, Belgium, which is housed in this extraordinary architectural space by Francesca Torzo, a brilliant architect. The original version explored ideas of semi-public, semi-private spaces—such as train stations, thresholds, and lobbies. So when Fiona Liewehr invited me to show it here in Vienna, at Franz-Josefs-Kai, I immediately felt it would be a continuation of that dialogue, but also an important transformation.

The idea of a traveling show brings up a few problems; there is a certain narrative, and you want works to be together, but in a new space, there could be factors that just mean that your plan cannot function in the same way, so there must always be orchestration between lots and lots of different factors. Not only the space, but also the status of the collaborations—I’m always thinking of the people I’m working with, and I try to ensure that their contribution is presented in the best possible way. One thing that came out of my research in preparation for „Orchestrion“ and something I want to really underline is this respect for mass entertainment and the idea of seduction and beauty, joy, and illusion.

I remember standing near that second entrance of the space during the opening talk. It felt like a spontaneous stage, where things unfolded naturally. On the other side, that frontal main entrance with the window creates this strange double window situation. And not to forget about the cellar, it created three very different moods. Could you speak about how you approached the positioning of the works and murals concerning these fragmented entry points and architectural flows?

That’s a beautiful observation. What you’re describing is one of the main creative and logistical puzzles of a traveling exhibition: you have a conceptual and spatial logic developed in one site, and then you need to re-choreograph everything in a completely new environment. That’s not just about architectural dimensions—it’s about mood, flow, proximity, and access. At Franz-Josefs-Kai, those three architectural conditions—the windows, the indirect entrance, and the cellar—each offered their register of intimacy or exposure.

So yes, I thought a lot about how the audience would move through them, but also how works would resonate when viewed from unexpected angles or levels. The display strategy became a mixture of applied arts, advertising, and museum presentation. But what underpinned it all was a kind of respect for seduction and surface: a celebration of illusion, of beauty. I didn’t want it to feel sterile or overly conceptual. I want people to feel drawn in, delighted, and curious. Then the conceptual rigour creeps up on them unexpectedly.

I always want things to operate with the visitor in the same way when I enter a beautiful space, it makes me feel good, and it makes me want to go further.

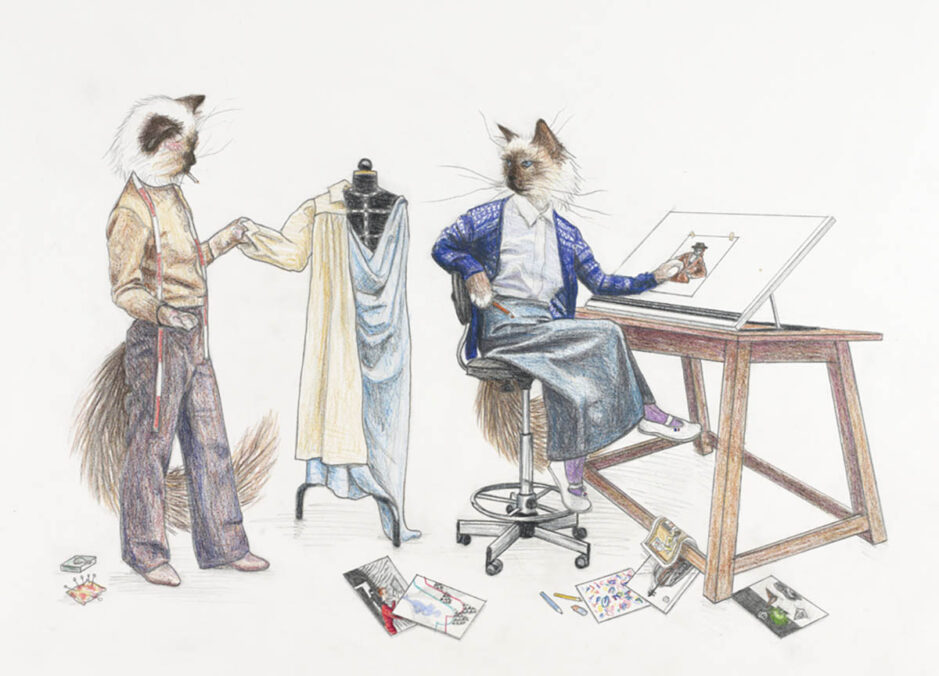

When you speak of seduction, entertainment, and beauty, I also think about fashion and decoration. To quote you, you once said in another interview that „art could also be a cat in a dress.“ As in, something that might seem superficial or silly to others, but for you, there’s depth and intention behind that gesture. What does mass entertainment mean to you? How do you relate to the masses?

I love that you brought up the “cat in a dress.” I do return to it a lot. I’m going to. I always imagine the idea of being in art school and taking your drawing of a cat and a dress to a critique in the class, and how it would just go against so many ideas of what we think of as, like, quality or serious art.

That drawing of a cat in the dress was important for me because it crystallized something: that joy, fantasy, decoration, and sentimentality are not less than. They’re powerful. And often dismissed. So when I think about mass entertainment, I think about that tension.

I grew up loving pop, fashion, sitcoms, and department store displays. There’s something deeply human about wanting to be entertained, to be moved by color, texture, and sparkle. And I think there’s also politics in how we frame and value those things, especially when they’re coded as feminine or decorative. In my work, I’m not trying to critique that from a distance; I’m trying to immerse myself in it, to elevate it, and to show how these “mass” languages carry rich emotional and cultural meaning. Sometimes I think it’s like writing a love letter to seduction itself.

In this kind of fragmented moment of social media and AI, I’m not sure what the masses are, but it’s just that there’s always going to be that binary or this tension between high culture and mass culture. That’s somehow still there; even after we’ve been in the modern world for so long, it’s still a provocation to prioritize the interests of, let’s say, working-class women.

You remained quite absent from social media. You’re one of the few artists I know who isn’t actively managing a public profile. And this is an art world that increasingly resembles a popularity contest, especially around fairs, online previews, and “likes.” Or maybe you have a secret private profile we don’t know about?

Well… I am on Instagram. But honestly, my feed is mostly cats in dresses—and occasionally, dresses without cats, or cats without dresses [laughs]. I’m forty-eight, so I suppose I feel incredibly lucky to have caught what I’d call the last train carriage on the final train leaving a previous kind of art world. The kind where commercial galleries took risks on artists and nurtured a career. I was taught at art school to document my work, write about it, and put it into the world myself. I emerged from that with a strong DIY sense of independence. And crucially, I benefited from things like decent unemployment support and thriving artist-run spaces in smaller towns. All of that gave me a very solid foundation, and frankly, I’ve just never needed to build a public identity around clicks or followers. That said, I’ve still made some meaningful contacts through Instagram. But I also recognize that it has this addictive, quick-hit quality. I see younger artists making work specifically for the screen: not even for documentation, but for that camera-frame rectangle. That’s a kind of aesthetic constraint I can’t participate in.

It became quite dominant, especially for my generation. I am almost thirty, and in the last decade, especially during art studies, we’ve been obsessed with that rectangularity. Not in the literal sense of framing a canvas, but the idea of how a work reads in an image, in a feed, in the virtual “white cube.” It could be pretty exhausting.

For me, there’s also the mental health angle to consider when it comes to social media. I make large, slow works—some of them taking more than a year to realize. Like, panels upon panels, layers upon layers, across many collaborators. So the rhythm of my practice just doesn’t fit the dopamine reward cycle of instant feedback. You wait a year, sometimes more, and when the work is finally done, you’re often already over it. You’ve moved on emotionally or intellectually. There’s no sugar rush, no “hit.” So, I’m very cautious. I know where the real rewards lie for me, and they’re not in that feedback loop. I can respect the tool, but I also need to protect the space in which I work.

![Anonymous Youth, Donatello John the Baptist 1.1., Donatello John the Baptist 2, 2019 Oil on fiberglass plastic. Donatello John the Baptist 1.2., 2019, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Cologne/New York. Karusellorgel [carousel organ], Wiener Prater, Karl Soukup for Fa. Stiller, 1931/32 Collection of the Wien Museum, Vienna.

Lucy McKenzie, Orchestrion, fjk3—Contemporary Art Space, 2025. Photo: Lisa Rastl](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/interview-lucy-mckenzie-09.jpg)

I still think we need to keep having these conversations because platforms like Instagram have become lifestyle companions, especially post-COVID. But shifting now, I wanted to bring up something in the exhibition that stayed with me: the magazine piece with the image of you in your teen years, next to a drawing of a portrait of Adolf Loos. That one left me completely shaken. At first, I wasn’t even sure if I was “okay” with it, morally or ethically. It hit this deep nerve, and I couldn’t quite figure out why. Maybe because it tapped into questions around taboo, shame, and the aesthetics of visibility. It left me wondering: Would it be easier to talk about difficult experiences if these things had been exposed all along?

I’m so glad you brought that up. I’ve recently made a series of paintings that reproduced these magazines I was part of: just still life paintings, very rendered, very formal. It fit the format of the art fair presentation. For this show in Vienna, I knew it had to be the real thing. The actual magazines. No translation. No safe distance. Just: flesh, print, genitalia, history. The choice to include them was incredibly deliberate. It destabilizes. It introduces risk. It says, “This isn’t decoration. This work means something.” And once you feel that shift, everything else in the space changes. The bodies, the narratives, and even the objects take on new intensity.

I believe in vulgarity—not as a shock tactic, but as a curatorial strategy.

That work recontextualized the whole show for me. And I have to say, it made me realize how rarely we see that kind of risk in exhibition-making today.

And the risk isn’t only aesthetic. It’s also ethical and historical. That material is full of underage implications, of false innocence, of seduction scripted through power. I’ve been obsessed with staged spaces for years: vintage displays, shop windows, and this was like finding the source code. I realized, “Ah. Even back then in my teenage years, I was drawn to the architecture of availability.” That’s been a motif in my work all along. And with Loos, I feel much aligned with the women he married: the young women who used their consumable bodies as passports to culture, experience, and access. I don’t feel exploited. I feel like that was the deal. But it should have remained complicated, and I wanted that complexity to be visible, not whispered.

And I think that’s part of the social impact of the exhibition. Not just visual pleasure or spatial flow, but deep, lingering disturbance. And speaking of space, I wanted to ask about the panoramic train carriage bar—that little mobile landscape scene. It felt so immersive but also bizarrely dirty, like it could be used by an abuser in a film set. That uncanny vibe stuck with me.

That piece was built with exactly that contradiction in mind. It draws from 19th-century fairgrounds, panorama rides, and illusionistic devices that were both public and private. You could close a curtain, disappear inside the space, and temporarily vanish from the rules of society. Stefan Zweig writes so beautifully about that era of sexual repression, how small, clandestine spaces became arenas of enormous emotional intensity. I see that carriage as a bit of a stage, a bit of a confession booth, and a bit of a porno set.

Disneyland, for example, when it was built, was designed to be the opposite. Clean, visible, family-friendly, no corners, no queers. But I’m always more interested in the corners. The sites of leakage and desire.

And finally, the piece “Loos House” that looks like a wooden “castle,” like a toy architecture structure made of canvas and wood.

Yes, Loose House. I originally built it after visiting the Villa Müller in Prague and then the Alhambra in Spain—two very different buildings, but both centered on watching and hiding. A friend later told me to read Beatriz Colomina’s writing on surveillance and domestic architecture—and it clicked. That’s what I had been sensing all along. I first showed the piece with painted Arabic patterns, but it’s become this kind of recurring architecture in my practice, a stage, a screen, a shelter. A place where bodies are seen and unseen. And yes, like you said, it’s a playground, but it’s also a fortress. Both things at once.

During the time you were researching for the show in fjk3, you also mentioned exploring dating apps for the first time. You said something that stayed with me: that you saw a parallel between the anonymous space of hook-up apps and the social spaces of the 19th-century fairground—the Prater as a site of class mixing, desire, and performance. I loved that.

That weird, anonymous intimacy of the fairground and now, of dating apps. Both are spaces where normal social rules bend or break. There’s something theatrical and disorienting about both. It’s something I want to explore further.

When I was a teenager, I read American Psycho, probably too early, but I still enjoyed it a lot. I see that world of the yuppie, the misuse of power, seduction, and violence running through your work. I’d love to hear where that comes from for you.

That’s such a rich topic for me. Over the past few years, I’ve made monumental paintings in the style of socialist murals: Diego Rivera-type frescos. I’m fascinated by how art reflects ideology. Especially when it’s been dismissed as politically “polluted”—like Soviet or Mexican propaganda art. That’s changing now. We’re rethinking value hierarchies.

American Psycho felt like the perfect subject for that kind of rendering. It’s about hyper-capitalism. That man’s body is a construct. A sculpture of consumption. And Christian Bale, this skinny English actor, transformed himself into a perfect capitalist object. I found that fascinating. What happens when you paint him? Especially knowing he’s a kind of idol in certain incel and right-wing online circles. The scene where Bale showers and describes his product regimen, apparently, all the women on the film set just stopped and stared at him. That reversal of the gaze—it moves me. Instead of a Hitchcock situation, where he was filming an iconic scene with Janet Leigh in the shower. This time, we get a male sex object, happy to be looked at. That power shift is erotic. That’s the kind of image that gives me chills. And that’s exactly the kind of image I want to paint.

You’ve worked so intensely and fearlessly, sometimes with people very closely. But collaborations or friendships don’t always last. How do you navigate that risk?

Sometimes those collaborations end. Friendships end, too. But I’d rather always take that risk and live and work to the maximum than be cautious. I’d rather take that step and live with the consequences. It goes back to those early images, working with Richard Kern, being naked, and knowing from the beginning what I signed for. You’ve seen my genitals—there’s nothing you can shame me with. And it’s the same with my work. There’s nothing left to strip down. That’s why I like working with these forms of falseness and truth.

I want the work to be extremely truthful, even though it’s highly fake. Looking back at those old magazines and interviews I did, I was lying so much! And I understood even back then: don’t tell the truth. You can have my body, but you don’t get my thoughts. You ask me if I’m a dirty girl. I’ll say, “Yes, I’m a very dirty girl.” It’s fake. But going through that gives you a kind of truth, through the back door, through your eyes.

I enjoy how people can’t always tell what’s mine and what’s found or appropriated. In Belgium, we showed this huge organ from a dance hall, and people were like, “Did you make that?” And I’d be like, “No, of course not.” But the work has reached this level of production where it bumps up against “real” objects. Like, when I wear something and someone says, “Did you make that?” But I love that confusion. That’s the point; it’s destabilizing. In the train carriage, we used real train seats and a real window. The idea was: wait, what part of this did she make? What did she touch? And of course, lots of people make things for me. It’s all gotten a bit mixed up now, and I like that.

What are you reading or watching lately? Anything you’d recommend? And also, what advice could you give, especially for someone just starting in the arts?

When I left art school, I read almost everything by the British historian Eric Hobsbawm. His most famous book is “The Age of Revolution 1789-1848,” which goes from the French Revolution into the 19th century. He also wrote “The Age of Capital 1848-1875.” It’s very clearly written, just a straightforward packaging of how the modern world came to be. That gave me a great grounding. Additionally, a book that held significant meaning for me while creating the recent exhibition is Norman M. Klein’s “The Vatican to Vegas: A History of Special Effects.” It’s fascinating. It goes from the Baroque to the spectacle of Las Vegas. It’s a great read.

As for advice: I’d say, for most artists, the experience of making art is like shouting into a void. Feedback is rare. If you expect it, you’ll be disappointed. Same with exhibitions, don’t expect them to “make” your career or bring a flood of connections. It doesn’t work like that. What matters is working with people you care about. If you do a show that no one sees, but you made it with friends—people who pushed you, who made you grow—that stays with you. That carries you to the next thing. Don’t break the thread. If you feel isolated or dejected, keep doing something, even if it’s very small. Collaborate. I was in a band during my teenage years. I didn’t love performing, but I loved practicing. I loved the things you can build together. And even when I was in the Venice Biennale or had a solo show at MoMA, those experiences never matched the joy of working with people you respect. And these people don’t have to be from your art school cohort. Look to other generations or other disciplines—design, music. When you find someone with a similar worldview or ethos, that’s gold. That’s what I have with Beca Lipscombe—it’s a moral alignment, an ethic. So yeah: work with good people. To start, Vienna’s a great place to do that.

Solo exhibition: Lucy McKenzie – Orchestrion

Exhibition duration: June 06, 2025, until January 18, 2026

Address and contact:

fjk3, Contemporary Art Space

Franz-Josefs-Kai 3, 1010 Vienna

www.fjk3.com, www.instagram.com/franzjosefskai3

Lucy McKenzie – www.lucymckenzie.com, www.ateliereb.com

The exhibition “Orchestrion” is organized in collaboration with z33, House for Contemporary Art, Design & Architecture, Hasselt, Belgium, Galerie Daniel Buchholz Berlin/Cologne, Cabinet gallery London, and CRAC Sete, France.

Lucy McKenzie (born 1977 in Glasgow, lives and works in Brussels) gained international recognition with her illusionistic Trompe-l’œil paintings, where she blends the historical technique with contemporary, often political themes. She works in the expanded field of artistic practice, incorporating sculpture, painting, design, fashion, and architecture into her work and exhibitions. Her interest lies in the role of art and culture as a mirror of societal and political changes, not only within museums but also in the public sphere, advertising graphics, or political propaganda. A particular focus of her work is on the representation of women. In 2008, McKenzie co-founded Atelier E.B. with designers Beca Lipscombe and Bernie Reid, a company focused on fashion and design projects. She is also a curator and founder of a record label.