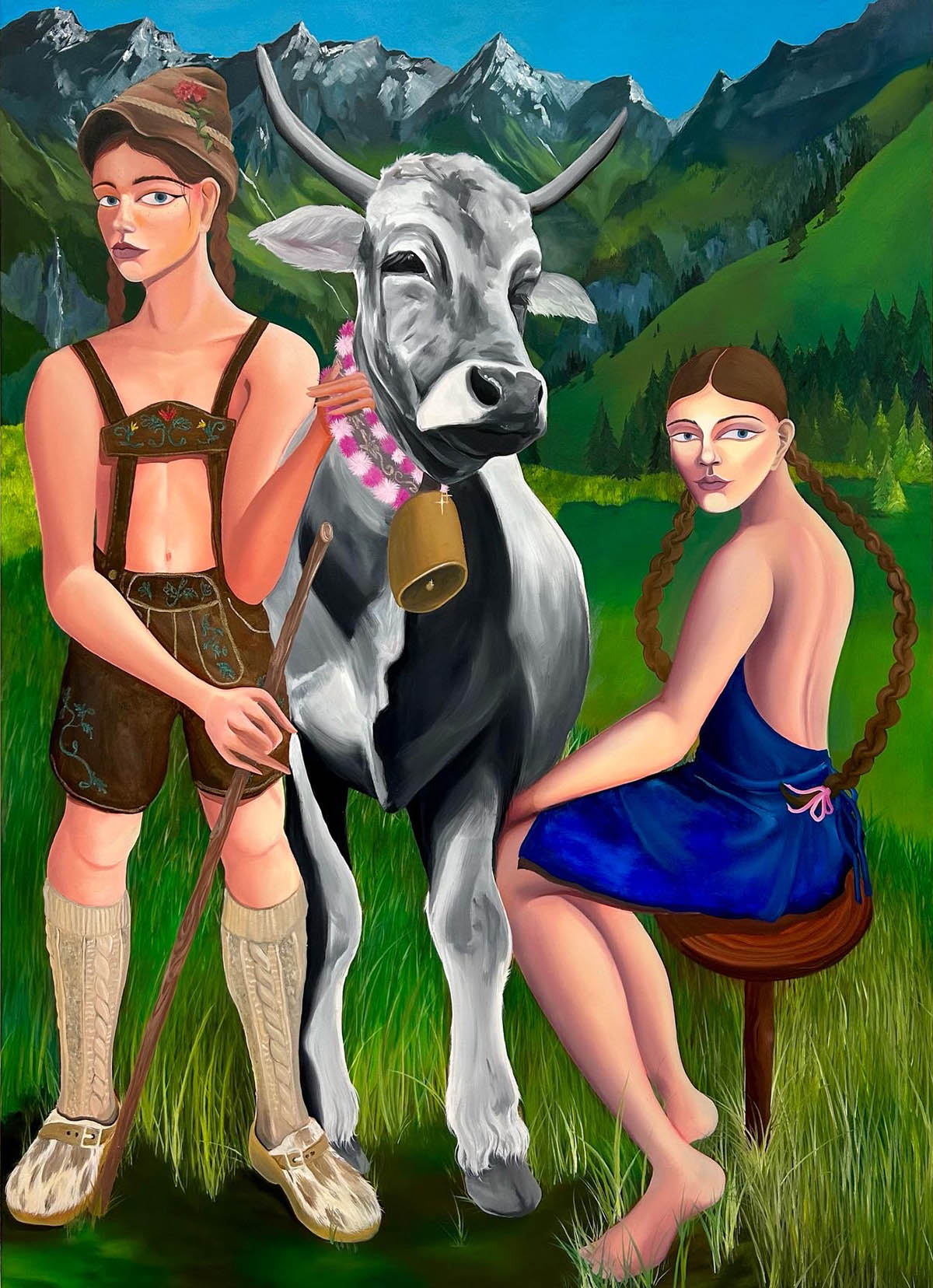

Melanie’s protagonists are women who use this distance to retell stories of Tyrolean origin, customs, and traditions from a feminist perspective. Rather than idealising the rural or indulging in conservative romanticism, her work critically engages with Alpine clichés and inherited visual languages. Drawing on historical genres and motifs from figures such as Defregger, Egger-Lienz, or Walde, she reclaims them for a contemporary, feminist reevaluation. Her paintings do not mourn a lost past; instead, they point to practices and contradictions that persist and must be reconsidered today. By foregrounding female labour and experience within a deeply patriarchal rural context, her work challenges traditional gender roles. It asserts that art history, too, can be written from a female perspective.

Your current exhibition, “Madler, ’s isch Zeit!” at the Städtische Galerie Theodor von Hörmann, has an interesting title. How did you come up with it? What does this phrase mean to you?

The phrase „Mander, es isch Zeit“ (Men, it’s time) is attributed to Andreas Hofer, the Tyrolean freedom fighter of the early 19th century. It is handed down as a call to action. The phrase has established itself as a mythical condensation: it stands for a moment of decision, resistance, and the mobilisation of a community.

„Mander“ explicitly addresses men. „Es isch Zeit“ marks a historical tipping point at which hesitation becomes impossible. The phrase functions less as a concrete slogan than as a symbolic wake-up call that continues to this day in Tyrolean collective memory. The exhibition title takes up this historically charged formula and shifts its meaning significantly. While Hofer’s call aims at the moment of rebellion, „Madlers isch Zeit“ opens up a protracted, structural process: It is less about a single historical moment than about a long-overdue emergence of visibility. Women are no longer conceived as mere supporting figures in a male-dominated history, but as active subjects, whose time is not just beginning, but is finally being recognised.

What are you showing in the exhibition?

I’m showing a total of 42 works, including paintings, drawings, and for the first time, a sculpture. I spent a lot of time in my studio over the last year, which is why 95% of the exhibited works are from 2025. It was clear to me that I wanted to show a sculpture, so I holed up in my garage in Tyrol last summer and spent two weeks, every single day, creating one. I carved the sculpture from Styrofoam using a chainsaw and various other saws, then covered it with plaster bandages and painted it. I braided the braids held by „flying“ birds from flax. For me and my work, it was very exciting to see how the character I’ve been developing on the canvas for years finally breaks free and enters a three-dimensional space.

Which memories from your childhood in the Tyrolean Oberland often emerge in your work?

I grew up in a small village surrounded by the Alps, where I spent much of my time in nature and on my grandparents’ farm. Animals were always a natural part of everyday life there. What fascinated me most was the close bond my grandfather had with his animals, a relationship shaped by respect, care, and a deep understanding of natural rhythms.

Many Tyrolean traditions are based on the idea of living in harmony with nature, respecting its cycles, and not trying to control it, but working with it. For example, life on the farm followed the so-called “farmer’s calendar,” which is based on the phases of the moon. It indicates which activities are best done on certain days, from mowing and harvesting to everyday tasks such as cutting your toenails (yes, really). The traditions of the Tyrolean Oberland are still deeply rooted there. I grew up with them, and they are often strict and require certain rules to be followed. At the same time, they bring joy, structure, and a strong sense of community, connecting the people within the village. It was only after moving to Vienna and gaining some distance from Tyrol that I began to realise how many small traditions had shaped my everyday life. This distance sparked my curiosity and led me to engage more deeply with them: What do they mean? Where do they come from? And who continues to carry them on today?

Can you tell me more about the work “Stollwerk”?

In the 1970s, my grandpa built a house for his family. He tiled the kitchen with these specific red tiles, decorated with green ornaments. Because he built the house himself, he was able to include small, personal details. One of them was a little connecting window between the living room and the kitchen.

As children, we were drawn to this opening. We looked through it, moved the door back and forth, and tested its function. But the best part was yet to come: on the shelf inside the window, there was always a candy tin that my grandma kept filled. And YES, my favourite candy was a caramel- bonbon called „Stollwerk“, taken from the tin through this opening, hand to hand, room to room. The object became more than an architectural detail: it was a point of exchange.

What does “homeland” mean to you personally?

Memory lies on this threshold. It’s also materially, in tiles, wood, nature, and rituals. Things that have been used bear traces. They store gestures, routines, and handovers. Homeland also arises where something is passed on and shared: knowledge, habits, a glance, a sweet. The threshold isn’t a protected space. It’s open. You can cross it, but you can also linger there. It allows for doubt. One can look back without going back. You can stay forever; „homeland“ doesn’t require staying, it exists even at a distance.

Perhaps that’s precisely what homeland means to me: a place of transition. A space where past and present touch. A safe space where you feel tolerance and welcome.

Are there certain traditions that you find particularly challenging or even provocative?

Traditions that defined village life and the yearly rhythm, guiding festivals and rituals. During Christmas time, the „Krampus“ figures roamed the streets, men in wild masks, loud, frightening. Their role was clear…as others observed, waited, and watched. Traditional costumes were worn on special occasions: men and women had their fixed gowns, their tasks, their places, their movements in the festivities. Every gesture, every step, every figure had been learned, passed down, and practised over generations. I remember the processions, the altars, the music, the shooting festivals. Everything was rhythmic, recurring, a lived pattern of belonging. At the same time, I sensed the line that defined certain roles, that made visible who led, who followed, who was in the thick of things, and who stood on the sidelines.

Precisely because they are so deeply rooted in society?

Traditions preserve knowledge, rhythm, and memory. They connect people across generations, giving order to the year and form to everyday life. They offer closeness, community, and a sense of belonging. Yet every tradition also has its limits. A line that determines who enters and who remains outside. For me, traditions arise precisely there. Not within the rule, not outside of it, but at its edge. At the point where one senses that belonging is something that is in flux. It’s not a place of rupture, but of pausing. Here, what is preserved and what is allowed to change becomes visible. Traditions do not lose their power by being questioned, but by becoming stagnant.

I see traditions as something that can sustain without clinging; it should enable connection without requiring exclusion, something that remains open for many bodies, many voices, many paths.

What thoughts should visitors leave the exhibition with?

I hope the visitors leave with the feeling that „homeland“ is not just a place, but lives in the colours, shapes, and lines we see, touch, and carry in our memories. My paintings tell of traditions, rhythms, and rituals. They tell of masks, costumes, and festivals, and simultaneously invite us to question the roles and boundaries they define. Every brushstroke, every texture is a memory, a moment captured and reinterpreted. Perhaps you will take away the realisation that we ourselves are part of this living tapestry: that we can shape, shift, and open.

That homeland arises, wherever we pay attention to forms, colours, and stories and where we paint paths to the future together.

Where can we see your work next? What have you already planned for 2026?

2026 will be a very emotional and exciting year for me and my work! I am currently working on my diploma and plan to finish the academy this June. From March 27th to August 30th, my work will be part of the group show „Animalia. Von Tieren und Menschen“ at the Heidi Horton Museum. From July until the end of August, I will be an artist in residence at the Künstlerstadt Gmünd, where I will be happy to welcome visitors to my studio.

Melanie Thöni – www.melaniethoeni.com, www.instagram.com/mellithoeni/