Let’s begin by talking about your life more broadly. What inspired you to pursue this path, and what has motivated you to run the gallery with such passion and dedication for so many years now?

In 1977, I founded the gallery at Kaulbachstraße 6 in Munich. Back then, the gallery was still relatively small, measuring approximately 120 square meters, especially when compared to its current size. However, beyond the day-to-day work in the gallery itself, what fascinated me most was exploring new paths with the artists and realizing projects outside the gallery space, including abroad. Before that, I studied art history in Cologne and later in Munich. But even before university, as a high school student in the Rhineland, I was already drawn to the arts, always “in medias res” (in the thick of things), as they say. I was living in a small town near Düsseldorf, where Günther Uecker also lived and worked. I first met him there when I was 18.

How did you meet Günther Uecker?

I have always had a deep interest in Eastern Europe. At the time, I was managing a rock ‘n’ roll band and even accompanied them on their final tour to Czechoslovakia. That was still during the Communist era when many things were forbidden, but that’s another story.

I had strong ties to artists from Eastern Europe. I invited artists from Poland and Czechoslovakia to exhibit at my high school, and I also took some of them to visit Günther Uecker’s studio. We also met other artists, like Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell. At that time, things were still relatively simple, access was easy, and the atmosphere was warm and welcoming. Artists had time on their hands; they were genuinely curious. Then came this young, eager student from Munich, accompanied by some artists from Prague, and they generously gave me their time.

Günther Uecker, like many of the great postwar artists, fled the GDR. It’s astonishing how many important figures came from East Germany: Gerhard Richter, Gotthard Graubner, Raimund Girke, and so on. Back then, they didn’t go to Munich or Berlin — it was Düsseldorf that drew them in. The Rhineland was the epicenter of postwar West Germany’s economic and cultural boom.

And there was Gabriele Henkel, a figure unlike any other: a formidable art collector and the wife of Konrad Henkel, CEO of the Henkel Group, who was an extraordinary hostess. Her salons were legendary, and Düsseldorf society supported its artists with a generosity that truly made a difference.

I was living in a student dormitory in Cologne during my university years. At that time, Wolf Vostell would send me oversized postcards whenever he staged one of his happenings. I kept all four of them and recently donated my entire Vostell archive to the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard. Even as a student, I was included in the circles of already well-established artists. There was a lot of energy, partying, drinking, but also an incredible generosity.

Looking back, many things may seem simpler. But it still takes courage to explore new paths and open doors. What drove you at the time? Was it pure curiosity, or something deeper?

I was always passionate about music, rock ’n‘ roll, and art, very different interests compared to most of my peers, who pursued law or medicine. I started by studying archaeology. I hitchhiked to Greece, visited Athens and Istanbul, wandered through the countryside, and explored ancient temples. That led me to consider a path as an archaeologist or perhaps an art historian, especially since I already knew many of the artists in the Rhineland. I leaped, and it turned out to be one of the best decisions I’ve made in my life.

Group ZERO, founded in Düsseldorf in 1958 by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene, later joined by Günther Uecker, became a major influence on post-war art. You became involved quite early on. What drew you to this avant-garde scene, especially Group ZERO?

It became clear to me very quickly that I was more interested in non-representational, conceptual art, art that engaged with material and form. My connection to art has always been physical, emotional, and not just intellectual. It was interesting to be part of the community, celebrating, engaging, and weaving connections with those around me.

How did things evolve from that point onward?

Even as a young person, I was welcomed by these artists with open arms. I never had to pay for a coffee in Venice; the artists always took care of it. If someone were sitting at a table, the party could start spontaneously. Later, through my art history studies, I took a trip to Florence with Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Braunfels, and it was there that I met Maurizio Nannucci. We’ve been friends ever since, and he’s still working in Florence well into his eighties. One encounter led to the next. Artists recommended me to one another.

I was known for my cheerful and sociable nature, which people in the scene really liked.

It must have been exciting to witness how access to art evolved over the years and continues to change. When did you decide, „Now I’m going to open my gallery?“ How did you approach your very first exhibition, and which artists did you start with?

During my studies, I had originally planned to write a dissertation on a Czech artist, Vladimír Boudník, who took his own life in 1968 as an act of protest against the Soviet invasion. It was a deeply political and emotionally charged topic. But then I was denied further entry into Prague, and I had to postpone the project indefinitely.

At that point, my doctoral supervisor, Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Braunfels, said to me, “Hey Walter, you have a real talent for working with artists, and you’re an excellent manager. Why don’t you do something else? Work with the artists!” Others around me kept saying, “Why not open a gallery? There’s nothing like that yet in Munich — it’s the perfect place.”

So, quite naively, I responded to a newspaper ad. A space was being offered. I met with the landlord, who looked at me, this poor student, and said, “No, we can’t give him a real contract.” But in the end, I was granted a one-year lease. I insisted, “No, I want at least three years, why keep it so short?” She replied, “If you go bankrupt, you’ll be glad to get out quickly.” And I said, “I’m not going bankrupt. I’ll manage.” So I jumped in with no money, no savings, but with a lot of enthusiasm and people who supported me. An entrepreneur from a local printing company offered to print all my materials free of charge for the first four or five years.

The first artist I showed was Jiří Hilmar, an artist based in Prague who had immigrated to Munich. It made perfect sense: I was already known for my deep connection to Eastern European art and artists. And right at the opening of that very first exhibition, I sold the largest work to the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, under the direction of Armin Zweite. He bought the piece for around 10,000 Deutsche Marks (€5,115), which felt like a staggering sum to me at the time. I didn’t even know what to do with it. That was the beginning.

How do you select the artists you work with? What are your core criteria when choosing what to show in the gallery?

I’ve followed the same clear line since the beginning. You could describe it as concrete, conceptual, abstract — but not figurative. What draws me in is art that explores the underlying dynamics of our world, more through structure, material, and form than through narrative. Of course, I can’t just rely on greats like Günther Uecker, Gotthard Graubner, or Raimund Girke.

I’m always searching for younger artists who speak to the gallery’s direction but bring something new. Every year, I strive to discover at least one artist to integrate into the gallery’s program. Most recently, I started working with Márton Nemes, a Hungarian artist I first met at the Venice Biennale. We now represent him.

Would you say you’re also fascinated by craftsmanship: by materiality itself?

Yes, absolutely. That’s always been there, perhaps, especially with the sculptors. It’s the way they approach their materials and their deep engagement with stone, wood, and metal. There’s something fundamental, almost primal, in how they work, shaping matter into something entirely new. I’ve always been drawn to that. It’s never been about sculptors who make figurines or representational works. For me, it’s about the transformation of material and the creation of new worlds. Technology plays a big role in that too, not just as a tool, but in terms of sustainability. That’s what makes art so unique: this dialogue between material and meaning.

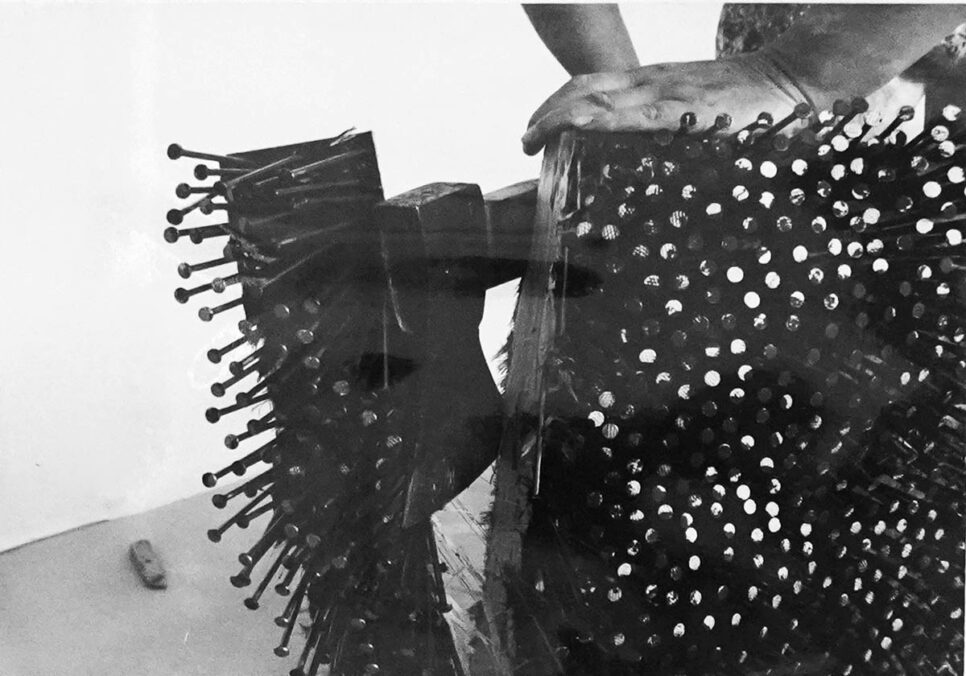

Take Günther Uecker, for example. He never made life easy for himself. Some of his pieces are so heavy, they’re difficult to transport. His nailed trees — massive wooden trunks densely covered in nails- are monumental, physical, and challenging. I’ve always enjoyed that physicality.

Where do you think Günther Uecker’s, or artists like him, deep inner drive came from?

It’s fascinating to realize how synchronously these movements emerged across Europe. In Düsseldorf, there was Group ZERO. In the Netherlands, there was the Dutch Nul group. Italy had Azimuth. In France, there was Nouveau Réalisme. These groups didn’t work in isolation; they fed off each other, enriching the whole scene. It was a dynamic, pan-European moment in the 1950s and ’60s. And I was right there in the middle of it. These were visionaries. They were fueled by the urge to build something entirely new after the devastation of the Third Reich. Germany was in rubble, cities destroyed, people traumatized, and suddenly there was this light, this movement toward optimism and new beginnings.

Just imagine: Heinz Mack driving into the Sahara in a reflective silver suit, playing with light and mirroring the sun. That wasn’t just performance: it was a manifesto. They wanted to generate hope, to build an optimistic world. These artists were pushing toward openness, experimentation, and possibility.

You were close to Günther Uecker. How did that personal relationship influence your understanding of his work?

When I opened the gallery, my thought was to start with a Günther Uecker exhibition. But he stopped me and said, “No, Walter — don’t start with me. Begin with your Prague artists — after all, that’s what you’re known for. I’m already too well-known. After me, where will you go? What could top that?”

He was right. What would I have done for the second exhibition? So I waited. Eventually, I introduced Günther Uecker to the gallery with an exhibition of his works on paper. That was the beginning. He showed me some early group constellations, and in 1982, I finally mounted the first major exhibition with him. He had never been shown in Munich before. At that time, Munich was one of the last cities to catch up with the contemporary art scene.

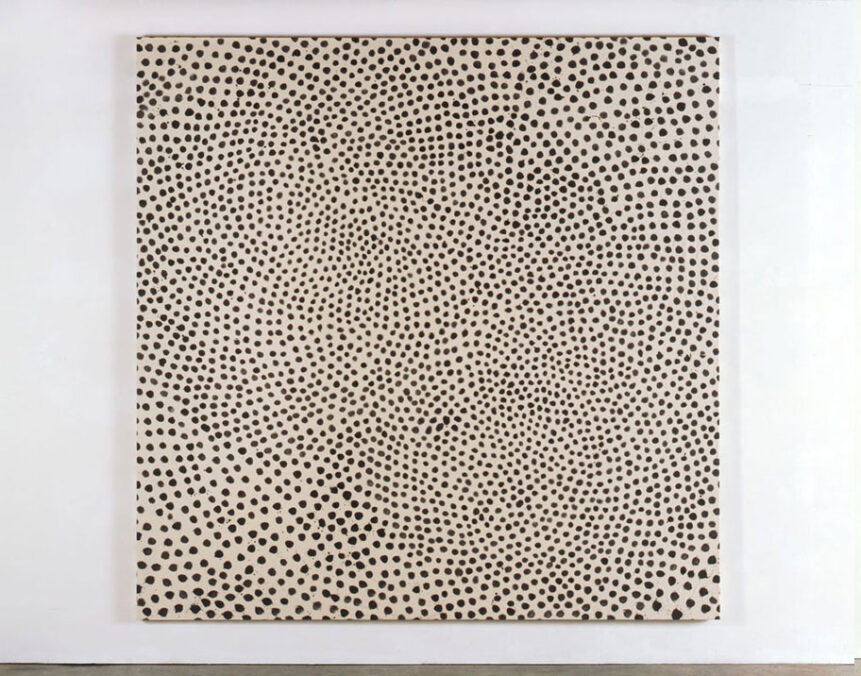

He certainly created a very distinctive body of work, especially with the nail as a recurring element.

He was fortunate and smart to find a symbol that resonated so deeply. That nail became his signature. And that’s something you see with many great artists: Beuys had his “fat corner.” These aren’t gimmicks; they’re long-term investigations. When you develop a theme, return to it, push it, refine it, and transform it; that’s when it gains real substance and significance. For me, that’s the essence of a great artist: a singular idea pursued to its fullest extent. Günther Uecker had that. He worked and reworked that one concept — materially, formally, spiritually — and in doing so, he created something enduring.

Günther Uecker has undoubtedly created a very, very distinctive work of art.

And what was his working process like?

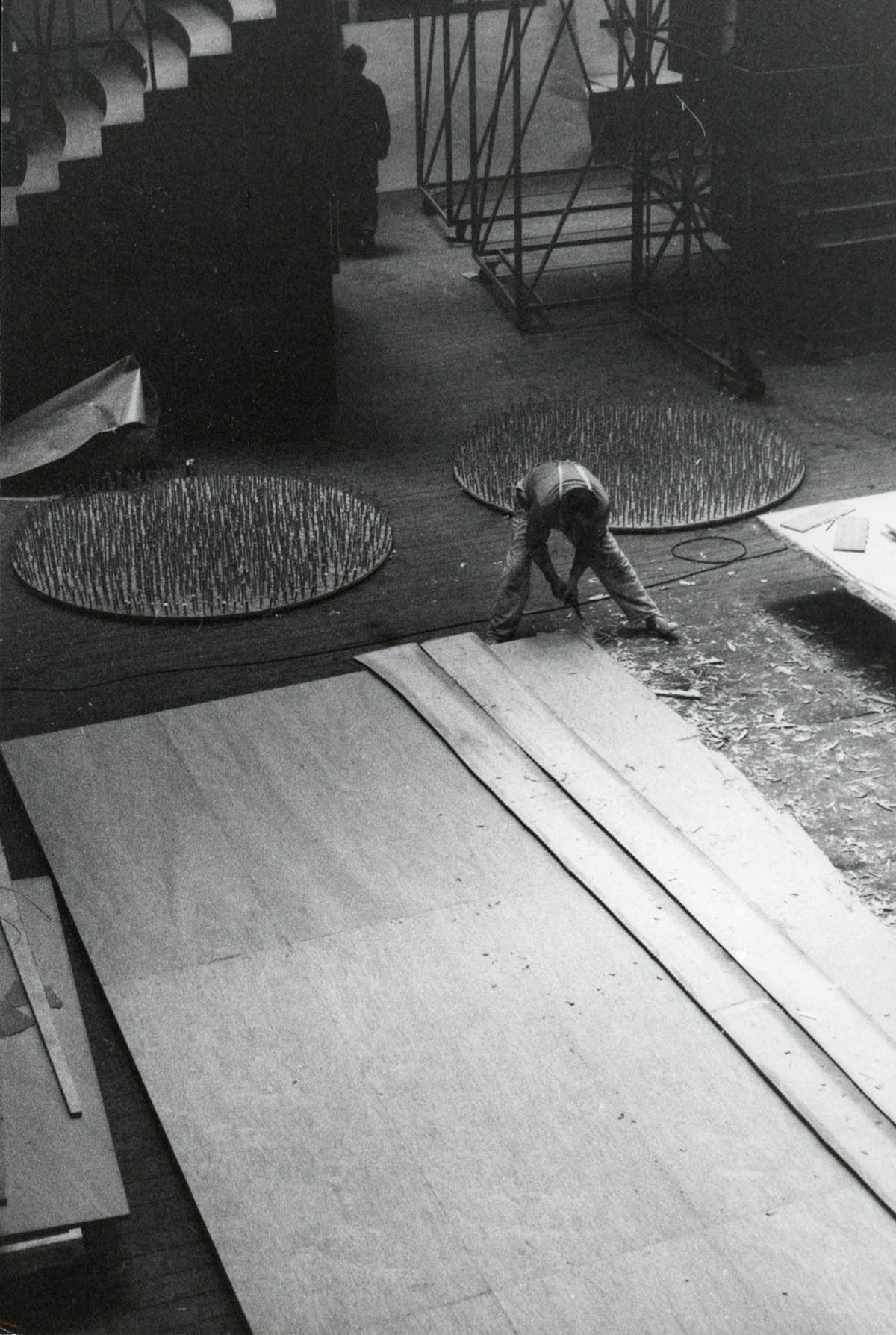

He crafted everything himself, with physical strength and active involvement. Tall, strong, and full of energy, this physicality was deeply ingrained in him from childhood. Constantly innovating, he developed new series and experimented with materials like ash, while also designing sets for opera and theater. Throughout, he remained fiercely independent, relying solely on his own resources.

He was also a very physical artist. Almost like a performer.

Exactly, he created happenings. In his studio, he built his worktables and furniture as part of the overall logistics. Günther Uecker worked entirely alone, without assistants or a studio team. Working in such complex ways requires everything to function seamlessly, and it is demanding. Despite the large number of works he created, his production was never fast. His works take time and are labor-intensive. They reflect the physicality, ritual, and repetition inherent in his process.

And politically, he was very reflective, wasn’t he?

He was a philosopher; he gave brilliant speeches about the state of humanity, religion, and conflict. He worked toward harmony among Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. For personal reasons, he rarely traveled to America, but he was constantly on the move in East Asia, the Middle East, and Iran. His last trip to Tajikistan was just two weeks before his death.

He was always a mediator of humanity. He also served as an „ambassador“ for Germany. There was always great excitement whenever Günther Uecker arrived anywhere.

What was he like personally?

A loving person who embraced everyone.

Your career also involved international crossovers, from Prague artists to global collaborations. Was that spirit typical for that time?

Definitely. Many artists grouped out of necessity. Financial hardship pushed them to collaborate and organize. If you created a group identity, institutions were more willing to work with you. This was especially common in Eastern Europe. ZERO only lasted a few years, but the community around it exploded with dozens of artists working abstractly and calling themselves part of ZERO.

How have you seen the German art scene change over the years?

In 1967, the Cologne Art Market—now Art Cologne—was founded. It was the world’s first modern art fair. Cologne and Düsseldorf were the pinnacle of the European art scene. Then Berlin rose, especially after reunification. Cheap rent and open space attracted a new wave of artists.

Munich, once considered provincial, caught up later. In the early ’80s, new professors transformed the Academy of Fine Arts. And then there was Bavaria’s wealth, the booming industry in Munich, and major investment in museums and cultural infrastructure. Institutions like the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, and the Pinakothek der Moderne grew stronger under directors like Armin Zweite, Helmut Friedel, and now Matthias Mühling.

Today, Munich is an excellent, proud cultural city. And the collaborative spirit continues.

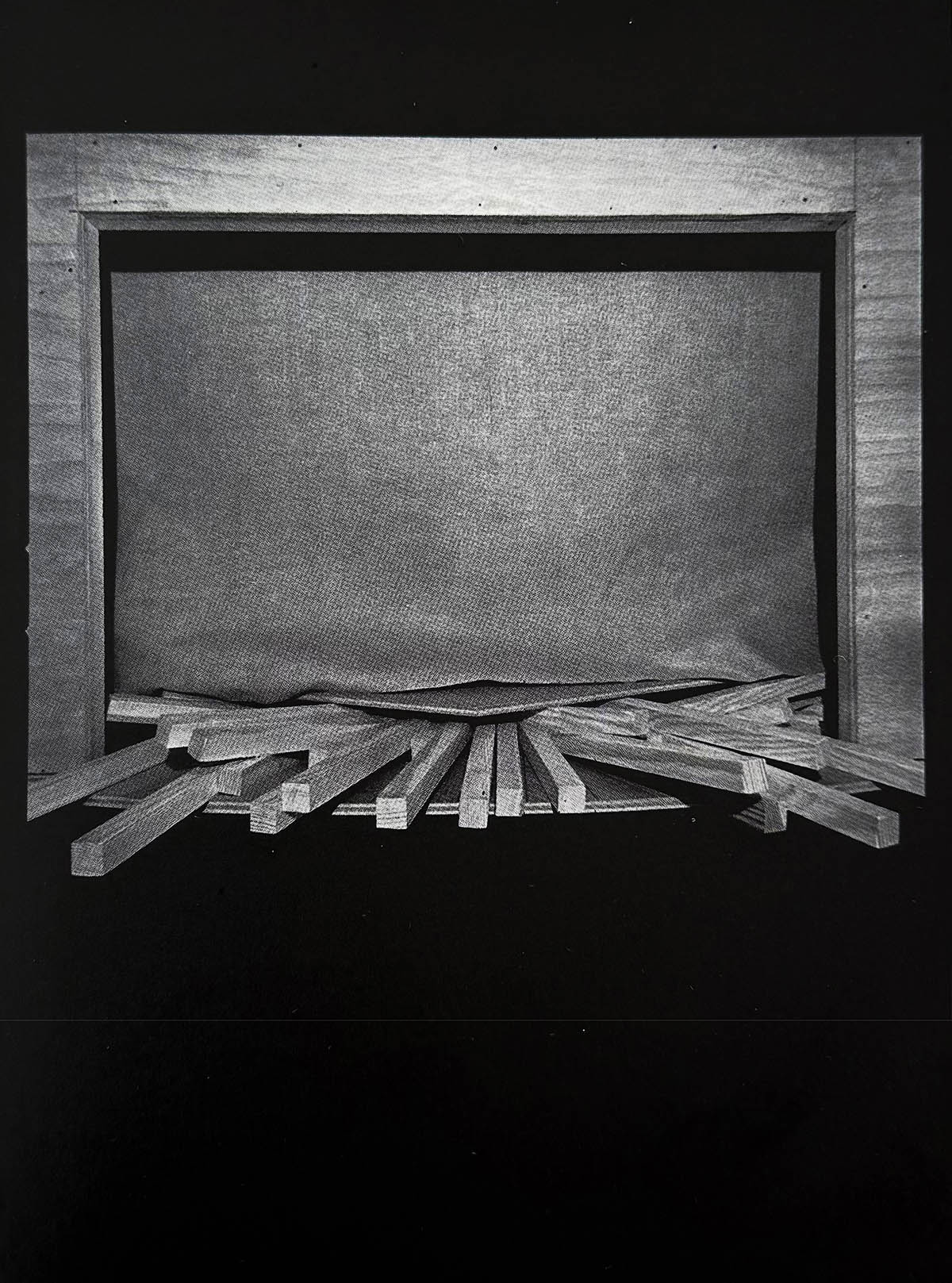

The exhibition Günther Uecker, stage sculptures and figurines for Lohengrin, Bayreuth 1979 opens on July 3rd. What will you be showing there?

It coincides with the Munich Opera Festival, a wonderful coincidence. I’m showing Günther Uecker’s famous stage design from Lohengrin in Bayreuth. These are wooden stage models: walkable, like architectural maquettes. We’re also displaying his costume drawings, the figurines.

What does this exhibition mean to you personally? It’s also nice to look back and remember the last time you saw it, isn’t it?

It truly is. It’s about memory. Günther Uecker wanted to attend, but he passed away very suddenly. I saw the opera back in 1982. I had received the tickets from him. That final performance has now become part of this memory.

Exhibition: Günther Uecker, stage sculptures and figurines for Lohengrin, Bayreuth 1979

Duration: 04.07.2025 – 09.08.2025

Opening times: Tue- Fri: 11 AM – 6 PM | Sa: 11 AM – 4 PM and on request

Address and contact:

Walter Storms Galerie

Schellingstraße 48

80799 Munich, Germany

www.storms-galerie.de

www.instagram.com/walterstormsgalerie/

Günther Uecker – www.storms-galerie.de/kuenstler/guenther-uecker/

Günther Uecker (1930-2025) was one of the most active, internationally successful, and popular artists in Germany. His name is inextricably linked with the legendary Group ZERO, and his nail reliefs in particular are highly regarded around the world. Most recently, in January 2025, Günther Uecker’s four ten-meter-high blue glass windows, “Lichtbogen,” were inaugurated at Schwerin Cathedral in his native Mecklenburg. Uecker’s multifaceted work also includes stage sets and scenic designs for opera and drama. In an exhibition that has long been planned with Günther Uecker as part of this year’s Munich Opera Festival, we are showing set designs and costume figures that Uecker created for Richard Wagner’s “Lohengrin” production at the Bayreuth Festival 1979-1982. On the occasion of his sudden death on June 10, 2025, we are showing selected works from Uecker’s oeuvre in a tribute. They shed light on our long-standing and friendly relationship with the artist, which goes back to the founding of our gallery in 1977. In addition to numerous exhibitions of our own, we have also realized international projects for Uecker over the decades and continuously accompanied his work.

Walter Storms Gallery is a leading international art gallery, known for its representation of renowned ZERO artists who have played a crucial role in the development of art since the post-war period. It was founded in 1977 by Walter Storms and specializes in contemporary, concrete, and conceptual art. The gallery works continuously with members of the Group ZERO, important representatives of the European avant-garde, Biennale, and documenta participants, and likewise promotes young talent. In addition, it operates its own publishing house, which publishes catalogs and books to accompany exhibitions in close cooperation with the artists. A special focus of the gallery’s activities is the administration of art estates: the gallery owns the estate of Günter Fruhtrunk (1923-1982) and administers the estate of the widow of Raimund Girke (1930-2002). On September 10, 2025, the Walter Storms Gallery will open a new location in Berlin at Potsdamer Straße 81A in Berlin.