In terms of the first impulses for the “Reeling Presence” project, what was the starting point? Francis Ruyter: The US was the context, since that’s where the original exhibition was supposed to take place. We talked a lot about the emptiness at that time in 2019 and 2020, both physical and psychological. In my imagination, it was a kind of urban emptiness, but also a larger disaster unfolding. I’d already been thinking about tents as an architectural form, as a way into other dimensions in my work. I’d been working with an archive of photographs from the 1920s and ’30s. That’s where the tents came from, and also the text. After we discussed the content and the mood. Walter selected a set of photographs he took in the 90s during his visit to the US.

Stefan, how did the sound piece for the „Reeling Presence“ develop? Can you walk us through the process?

Stefan Geissler: The whole process was strongly influenced by the pandemic, especially by the first lockdown at the beginning of the pandemic. During this period of being locked out/locked in, which is familiar to composers as ’self-seclusion,‘ it can be rather helpful for the composition process and has become a global phenomenon. Concerning the work itself, unlike with previous projects by Walter and me, I was not involved in the selection of the photos for „Reeling Presence.“ This was also a consequence of the pandemic. For me, at least, there seemed to be no overall theme this time from the photos; it was Francis who selected texts for the project.

And for me the aim was not to create a specific, identifiable mood, but rather to enhance the mood that was already ‚there‘ in the photos and texts.

Btw, the bells at the beginning are those of the Erdberg Church in Vienna, sampled directly from my open studio window. ‚False bells,‘ so to speak, because the work insinuates that everything that „happens“ here would be in „America.“ The selected texts then led me to the Alan Lomax samples/recordings.

You were working from home during lockdown?

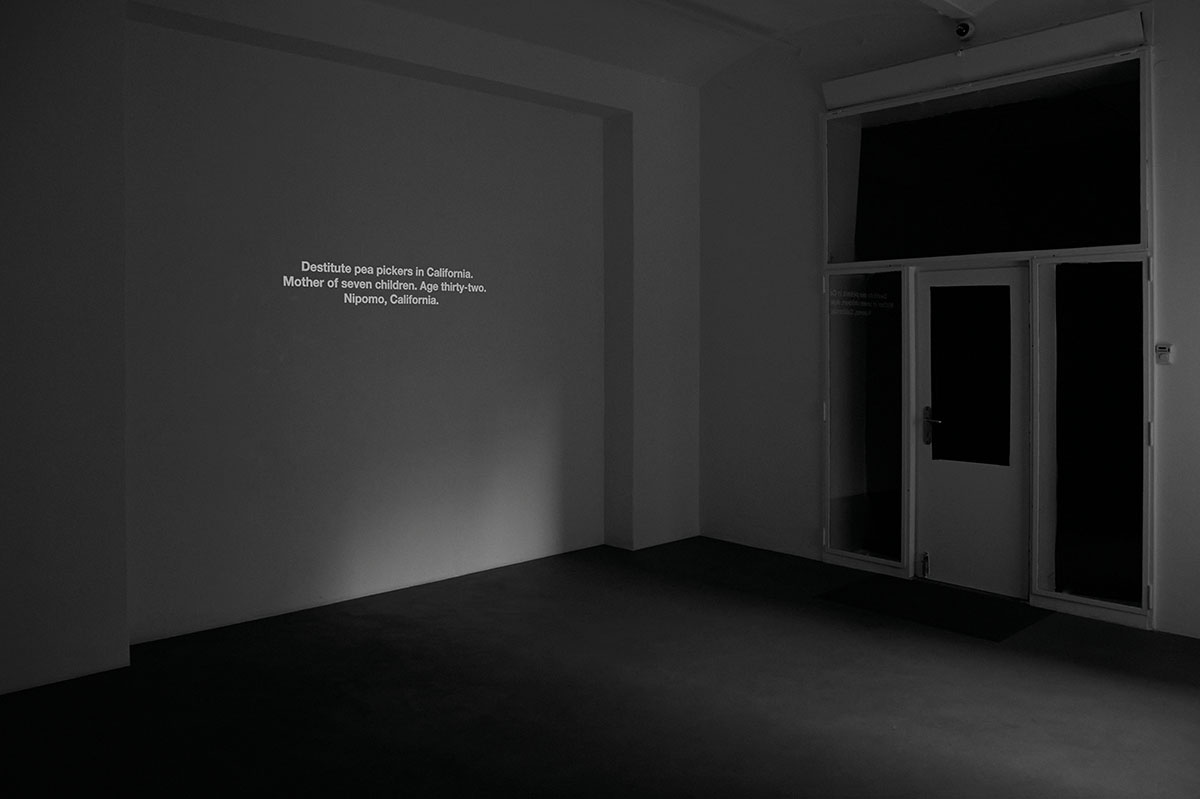

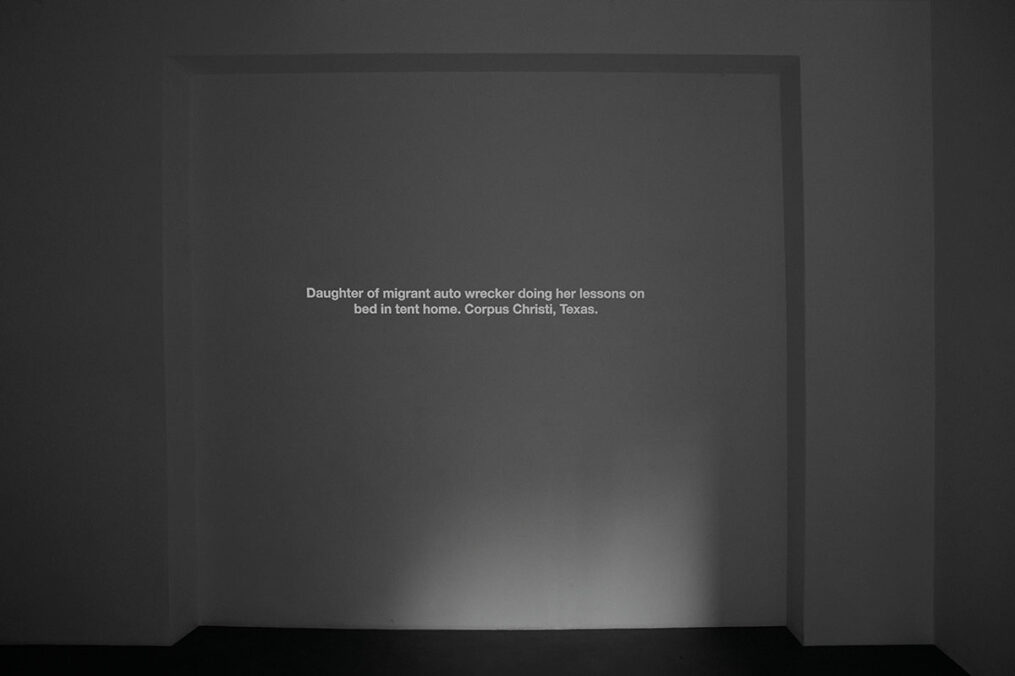

Walter Seidl: I have a huge archive of slides I haven’t scanned yet. I began looking for my own US photographs that showed empty places, scanned them, and created a selection. The captions interested me most; separated from their images, they carried their own parallel story. Text and images existed at the same time but were not directly connected, almost like overlapping layers.

Francis: Images and text create a kind of displacement. Even over the ten minutes of the video, there’s a loose narrative. And of course, that moment, the early pandemic, was a historic one. We understand that such catastrophic events become pivotal moments in history, as they serve as defining moments for individuals.

The project began in March 2020, connected to the fact that you weren’t able to go to the United States back then. Could you tell me more about that?

Walter: Yes, it was right when COVID hit. We were supposed to have an exhibition, a show at the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York (ACF). Then, the director of the ACF and the Austrian Embassy in Washington invited us instead to create a work as a kind of “bridge” between the start of the pandemic and the postponed exhibition.

The exhibition that was initially planned through the Austrian Cultural Forum happened later; was it connected to the “Reeling Presence” project?

Francis: Eventually. But at the time, I was the only one who could have flown to the US, and I decided to wait and travel with the others after the show.

Walter: We didn’t get to see the exhibition. It ended in February, and by the time I was vaccinated, it was already over. The exhibition and the project are connected only peripherally. We were discussing both projects at the same time, so some of the ideas overlapped, but not directly.

Francis, your work often connects past and present social structures and historical moments to the now. What’s your methodological approach for connecting art with the socio-political state in the world at the given moment?

Francis: I started with that archive because I wanted to make work about the 2008 financial crisis. It’s one thing to say, “This is about 2008,” but that’s abstract. In Austria, the crisis didn’t visibly affect daily life for many people. In the US, people with full-time jobs suddenly became homeless in a month. That experience made me think about emptiness, both physical and systemic. In this project, the juxtaposition of Walter’s New York photographs with my slides, some 25 years old, creates a bridge between different periods.

There’s also this idea of curation as identity-building: selecting, organizing, and ordering the archive.

Francis: For me, working with this archive connects to thinking about machine vision and AI. The archive is a closed set of well-known, copyright-free images that many artists have worked with. It documents a moment when American identity, especially the image of the small farmer, was being constructed, while industrial agriculture was taking over. So it’s a perfect intersection for topics that are very relevant today. And by recontextualizing them, new narratives are created that are both historic and contemporary.

Growing up in the US without money and living most of my adult life in precarious conditions. When COVID hit, I had friends who lost all four of their part-time jobs at once. For me, the tent motif in the work isn’t only aesthetic; it’s deeply tied to that lived anxiety.

The pandemic brought an existential shock, and on top of that came the constant news cycle. But even that media anxiety is a privilege; you need internet, electricity, and time to consume it. Many people couldn’t even access the information they needed for healthcare.

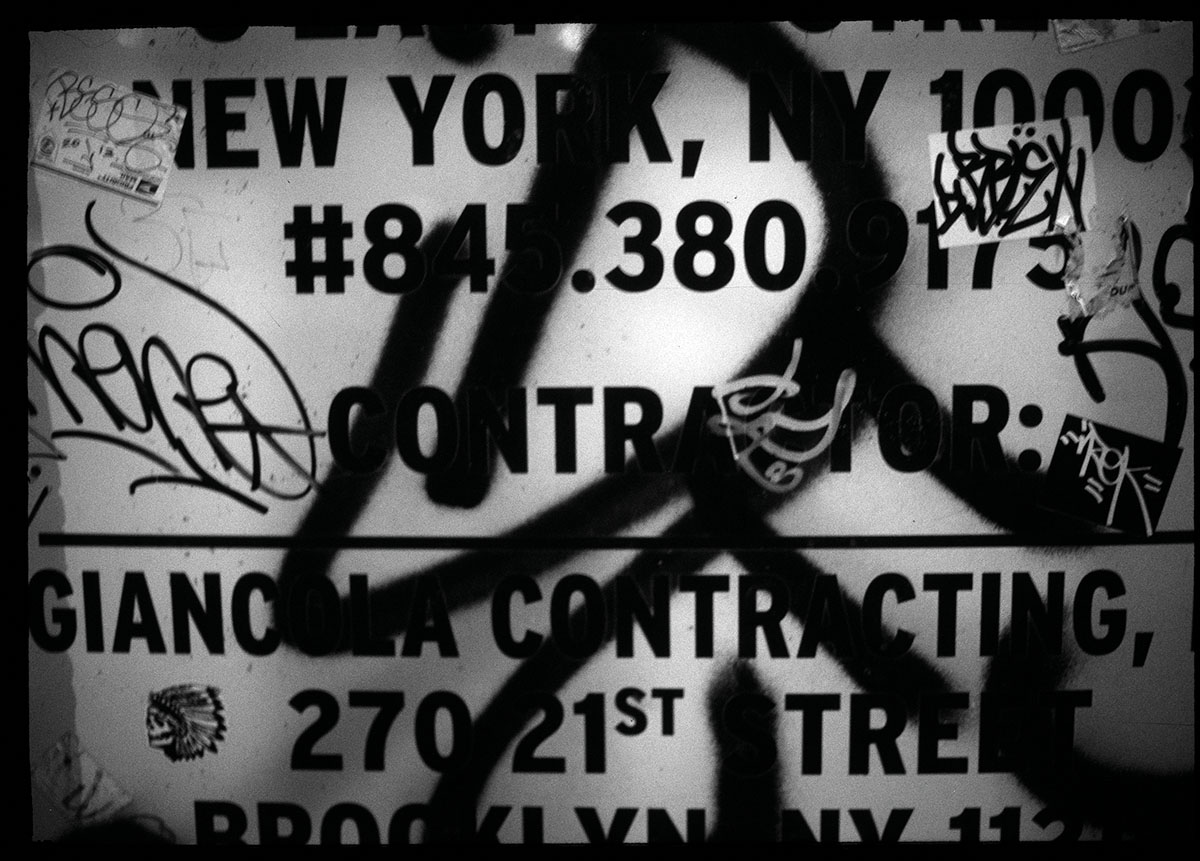

Many of my slides were already decades old when I scanned them, so even without intending to, they became part of a layered historical conversation, one that mirrors the empty streets of New York in 2020.

You said that catastrophe is a cycle; events repeat and echo each other in a visual loop that never ends. How did that idea feed into this work?

Francis: I didn’t want to play with “fake news” or media irony in this project. For me, the question of appropriation is different. When I started working with these images, I wasn’t thinking about appropriation in the Jeff Koons or „theft“ culture sense, that direct, almost literal taking. I’ve always felt that the women artists who engaged with appropriation, like Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, or Sturtevant, did something far more subtle and complex.

Now, if you want to talk about today’s media chaos, which had already intensified before the pandemic and then got tangled up with the Trump years and other huge social developments, there are many ways to respond. Some artists replicate that chaos, playing with humor or overload. That’s a valid approach, but it’s not mine.

For me, taking a picture and a text and placing them together is a serious act. It asks, why do they have this relationship?

How does one image change when placed after a certain text or before it? Does the text influence how I see the next picture? Does it refer back to the previous one? – Walter Seidl

Would you say that in this work there is a “play” with the viewer’s process of association?

Francis: A friend of ours said, for instance, he didn’t immediately realize he was looking at alternating text and images; he thought it was just a sequence of three or four images. That’s because the text isn’t declarative or didactic. It reads almost like a neutral caption, but it’s not describing the image next to it. It’s describing something else entirely: sometimes an imagined location, sometimes a past event, so the mind starts connecting things that aren’t connected.

Some of the texts are more complex, especially later in the sequence. For example, a date might appear „4th February“—and immediately you imagine a camp, a road, and a concrete factory. You start building a mental map.

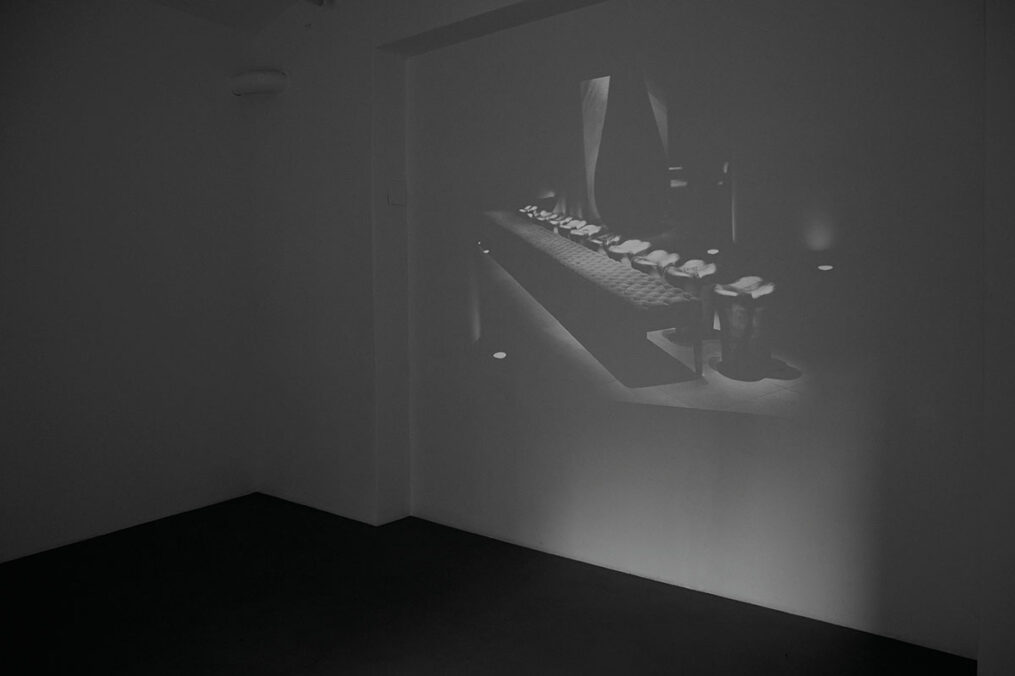

Walter: This is also a work you have to watch more than once. Online, it felt slower, even though the timing was the same. Here in the gallery, it’s projected, so you have the presence of the space, and you project your associations into it.

And here at gezwanzig gallery, people can also see the video from the street, framed through the window. It is almost like a moving billboard or video advertisement. The sound appears to be missing for passersby, but still, the gallery is open every Thursday. Could you tell me about the sound component?

Stefan: This raises questions around the completeness of a multimedia work. For example, it can be enjoyable to only read the libretto, but an entire opera is just something else. In this context—i.e., concerning the phenomenon of opera—the ‚visual level‘ (singers, costumes, stage design, etc.) can even distract you. But distract you from what? From the essence? Which essence?

In the end, everyone must decide for themselves what ‚the essence‘ of some piece of art is. As far as I’m concerned, I prefer to listen to the few operas I like at home with my eyes closed. Going to the opera usually disappoints me. In other words, I do think it makes the most sense, also in terms of doing the work justice, to experience „Reeling Presence“ WITH the music. Nonetheless, in my opinion, the individual parts of our photo-sound installation also ‚work‘ on their own. So, from this perspective, if the possibilities of reception are limited from time to time (e.g., only from outside the gallery window), it’s not that much of a problem for me. (You can listen to the music afterwards at home with your eyes closed: maybe this would be the most concentrated reception experience anyway.)

Walter: Stefan saw the selection of images and texts, then researched sounds from the 1930s. He found samples and layered them to create a kind of historical texture; you can hear some of those elements in the original version. They’re subtle, but they add another layer of context.

I haven’t observed people watching from outside, so I don’t know if passersby see just one image or stay to watch the sequence. But I would be interested to know about it.

Walter, in your work, there’s often this shift between images that include people and those that are devoid of them. Could you talk about these two different directions?

Walter: The whole thing started when I was studying in the US in the 1990s. I was fascinated by analog slide shows with sound. At the time, I was working with old black-and-white slides, not negatives, but positive images on film. The slide shows on my website are actually from that period. They often follow couples, people coming together, breaking apart, finding new partners, and repeating the cycle. Sometimes the images form small constellations: three people connected, fragments of different life stories. It’s about these shifts: finishing one chapter in life and moving to the next.

Over time, these images I used in the video work “Reeling Presence” become untethered from a specific period. They could have been taken 30 or 40 years ago or yesterday. There are no clear time markers in them for the viewer, but I remember the context because I was there. I had this mental library of iconic twentieth-century photographs before I even went to the US; I’d seen them in books, and then I encountered similar scenes in real life and felt compelled to capture them.

Do you see your practice as consisting of many different outcomes that are still connected by an underlying thread?

Walter: Yes. There’s a kind of continuity in my work; everything I make feels like part of one larger piece. I don’t think in terms of completely separate series. Sometimes, the connections are more obvious; other times, they’re less visible. When I look back after many years, the pieces start to speak to each other in ways I couldn’t have predicted.

Francis, your earlier paintings, from around the 2000s, are often described by others as colorful, pop, and happy. But you’ve said that’s not how you see them.

Francis: It’s funny: when people first saw my work, they never read the colors as “happy.” They were described as toxic, neon, and nuclear. But now, in Vienna at least, people tend to connect me with this colorful pop aesthetic. I’m not interested in sticking to an aesthetic narrative.

As an artist, I see everything I make as part of one central project. I’m always adjusting and responding to how people interpret the work.

You’ve talked about waiting for a different “subject position” in your practice. What does that mean for you?|

Francis: It’s about relationships: with my materials, with the context I’m working in, with the people viewing the work, and with other artists. All of these relationships change over time, whether I want them to or not. When I first started, people read my work differently than they do now. The way people look at pictures has shifted. When I stepped out of the accelerated art market cycle, I entered a space with different possibilities and challenges. I’m learning to accept that shift and work with it.

Exhibition: Walter Seidl, Francis Ruyter, Stefan Geissler: Reeling Presence

Duration: July 17- September 05, 2025

Address and contact:

gezwanzig gallery

Gumpendorfer Straße 20, 1060 Vienna, Austria

www.gezwanzig.com

www.instagram.com/gezwanzig/

Walter Seidl is a Vienna-based artist, writer, and curator whose work blends narrative photography, proto-filmic scenarios, and sound to explore the intersection of reality and fiction. Holding a PhD in contemporary cultural history, he has exhibited internationally and served as a board member and co-editor for Camera Austria. www.walterseidl.net, www.instagram.com/walter_seidl/

Francis Ruyter (b. 1968, Washington, DC) is an artist with over 30 solo exhibitions worldwide, whose work is held in major public collections including MoMA, SFMOMA, and Le Consortium. Based in Vienna since 2003, he has curated numerous exhibitions, taught at the Academy of Fine Arts, and is a member of the Vienna Secession. www.theruyter.com, www.instagram.com/_ruyter/

Stefan Geissler is a Vienna-based musician and sound artist whose work blends acoustic instruments like harmonica, toy piano, and cello with electronic processing. He collaborates widely, nowadays primarily with Marta Beauchamp in their music and performance duo beauchamp*geissler (https://bg.klingt.org), but also with other artists, often combining music/sound with photography and conceptual art. geissler.klingt.org, www.instagram.com/stefan._.geissler/