The Kunsthalle Wien Preis 2025 is presented in collaboration with the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien and the Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien. The prize is aimed at recent art graduates who studied in Vienna. How do you see this prize functioning as a bridge between academic study and professional artistic practice?

Hannah Marynissen: I think the prize is both a big opportunity and a challenge. It’s awarded by one of the main institutions for contemporary art in Vienna, so the audience is much broader. But of course, when we bring these artists into our house, we’re also asking them to meet the demands of an institutional exhibition space. They may not be accustomed to the high level of organization and collaboration that an institution demands. At the same time, they’re at the beginning of their careers and often have side jobs; preparing an exhibition over four intense months while working these side jobs can be a real challenge. It’s a great experience, but also a steep learning curve.

Anna Marckwald: Hannah has been working on curating the Kunsthalle Wien Preis for several years now. I’m new to the team, but I also see it as an important gesture for an institution to say, “We want to share our space and resources with emerging artists and support them in finding their way into the professional art scene.“ At the same time, the timeframe for preparing the exhibition is quite tight. Anyhow, both artists managed to produce new works under these conditions, which is impressive. This was only possible thanks to their extraordinary commitment, extra effort, and working outside typical hours. It’s intense, especially for early-career artists.

Does the Kunsthalle Wien Preis winners’ exhibition easily attract a broad audience? Not just people from the art universities, but also tourists or the general public?

Hannah: Yes, definitely. When all Kunsthalle Wien exhibition spaces are open, everyone who visits the main building in MuseumQuartier will also get the ticket for the Kunsthalle Karlsplatz space. Exhibitions here are always quite well attended.

Our job as curators also doesn’t end when the exhibition opens. It’s not just about putting on an exhibition and then leaving it. We also organize a public program to attract even more audience—guided tours, talks, and collaborations with different groups.

Last year, for instance, we worked with Queer Base, the organization that supported Rawan in his asylum process. I organized a guided tour with them through the show, which was really meaningful. It’s about activating the exhibition and reaching audiences beyond the usual art crowd.

This year, on the 10th of December, there will be an artist talk with both Jonida Laçi and Luīze Nežberte—that’s the main event!

Anna: It just makes a lot of sense to organize a common talk with both artists this year, because we always considered the exhibition as a whole. Jonida and Luīze already knew each other’s practice, and there are quite a few parallels between their approaches —their works just flow together naturally.

How did knowing each other’s practices help shape the collaboration?

Anna: We were lucky that there was an appreciation of each other’s work and practice, and also a personal connection between the two of them. From the very beginning, there was a willingness to work collaboratively. It was never a matter of dividing the exhibition into separate sections; instead, we were thinking together about how to intertwine their practices in the space.

Hannah: As curators, but also in collaboration with the artists, we approached the exhibition this year as a whole. That was really possible because both artists appreciate each other’s work and were committed to finding the best ways to work with the space in its entirety. In the end, that approach helped the exhibition step away from the notion of it being just a “prize show”; we’re presenting two practices that are compelling on their own, and I hope visitors experience that.

In terms of curatorial workflow, did you divide responsibilities? Or was the whole process fully collaborative?

Anna: It emerged organically. I conducted an interview with Jonida and Hannah with Luīze, but generally, we communicated as a group of four—the two curators and the two artists.

Hannah: Even when writing the handout text, we divided it between Anna and me. But then we would exchange drafts, merge them, and create a single, unified text. The handout walks visitors through the exhibition and highlights connections between the two artists’ works, and there are so many.

Anna: …The closer you look, the more connections appear. Both the conception and installation of the show were a collective effort; all four of us were in the space during the install, discussing positions. It was always crucial to us to balance between institutional requirements and room for experimentation. Of course, we needed to plan a lot; some of the works had set positions, but we tried to maintain room for experimentation, testing different arrangements as a team with the artists once the works were in the space.

Let’s talk about the space itself. How did you approach the exhibition layout?

Anna: Both artists explore notions of perception and perspective, but in their own significant ways; the important part of the process was turning points of view, looking behind surfaces, and reflecting on how artworks are presented, thus how the artist’s conceptual approach could also be transferred into curatorial decisions and the design of the exhibition space.

It’s very much about the interplay between the two practices, spatial experimentation, and inviting visitors to engage actively with the works and their presentation.

How do the individual practices relate to this spatial strategy? Can you tell us more about their practices?

Anna: For example, the work Speech and Eulogy (2025) by Luīze – the walls in the middle of the space were rotated “the wrong way around,” to invite visitors to look behind them and change their perspective, thus applying a crucial method of Luīze’s but also Jonidas‘ work to the experience within the show. This emerged organically during a site visit with both artists; it just felt logical, as it creates a choreography through the space and subtly divides it into two, which also benefited the presentation of the other works.

Photo: Daniel Lichterwaldt

Recursion (2025), a new series of photos by Jonida, is hung nearby, on the other side. It captures the façade of a prestigious 19th-century shopping arcade from inside the stairway of the house, looking behind the surface to reveal the hollow structure of the statues decorating it. It opens a reflection on the illusion enhancing commercial strategies of the building, which creates a subtle connection to Luīze’s sculptural practice: looking behind architectural surfaces to deconstruct their cultural history and value.

Hannah: Nežberte’s work considers methods of collecting, quoting, and recontextualizing material via sculpture. Her works are deeply connected to vernacular architecture in Latvia, communal buildings created with local materials. Her diploma, We could listen much longer, but it is late by now (2025), focused on this architecture, and the sculptures in this exhibition reinterpret structural forms from those historic meeting houses.

Nežberte’s diploma presentation centered around sculptural reinterpretations of historical architecture, a piece referencing a pillar from the Gaides Meeting House (built in 1739 by Latvian followers of the Moravian Brethren). The original house was a meeting place for Latvian serfs and was destroyed in 1953 during the Soviet occupation. Luīze reappropriates the forms from a single surviving photograph, translating it into sculptural works that hold a handmade materiality—MDF, tape, visible joins—nothing is overly polished.

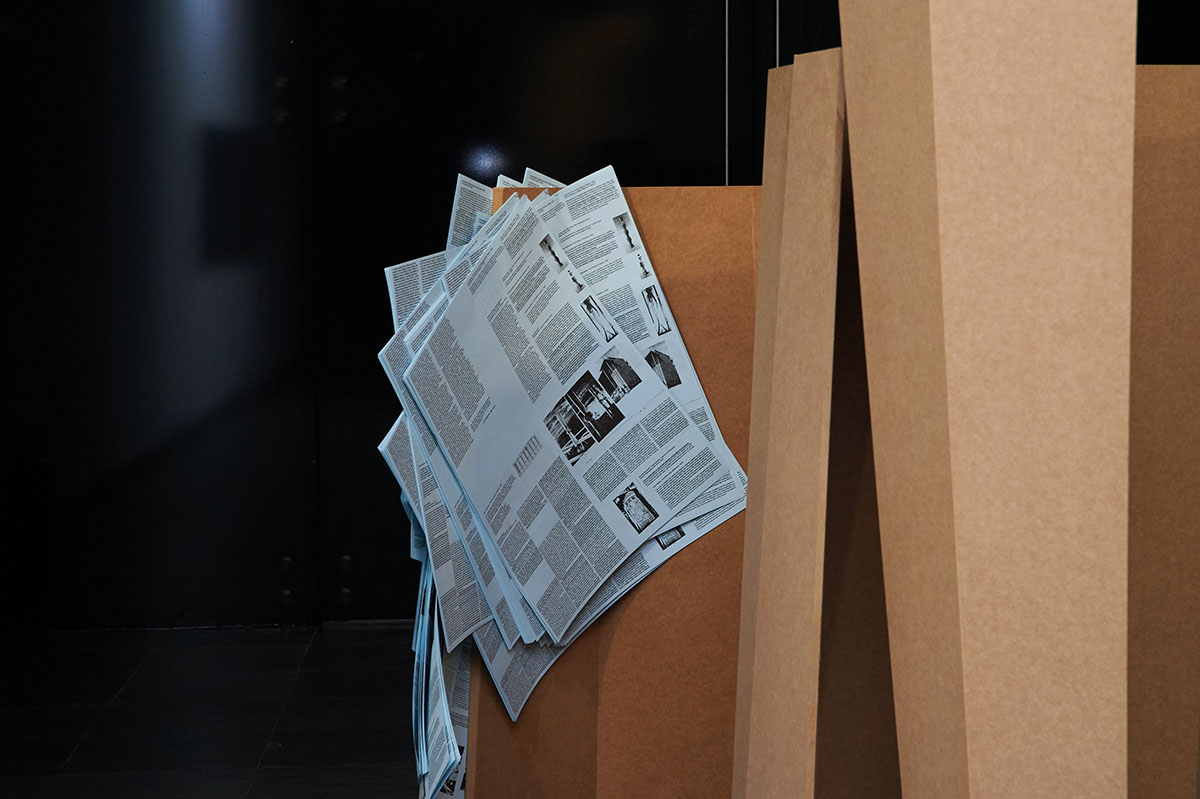

She wants to show the act of making, as well as the translation of historical forms into contemporary contexts. The installation in the back of the room Beings stability: an illusory sequence of fixations in space (while turning away from the ruinous present, disintegrating and entropic reality) (2025) – are actually fragments of her other structures that reference multiple sources, which she doesn’t try to replicate or reconstruct. Rather, in placing these elements in a new context, she’s attempting to open a space where they can resonate differently. This is made particularly clear in the installation’s single-sheet publication Bulletin (2025), which challenges ideas of authorship by bringing texts by marginalised authors in relation to canonised forms of knowledge.

Anna: Jonida was trained in film, and that background informs her artistic practice. Her first work presented in the exhibition, an installation consisting of the three films Planes, work, and The Fiction of a Doorframe (2022/2025), uses projections of moving image and projectors serving as sculptural works to explore ideas of perception, perspective, and the gaze that are crucial for both media. The title of Jonida’s diploma, Ajar (2025), was a conceptual starting point. The word ajar doesn’t exist as such in the German language. It is describing a state of being in between, a door, not fully closed nor open. You can see how this idea informs the presentation of Laçis‘ projections and how visitors have to engage with them: They’re seeing fragments, glimpses, thus behind the conditions of their production.

The films projected are footage that was originally sent to Laçi via a text message and filmed on a phone. It’s shot from the roof of a house—sometimes you see the ceiling, sometimes the camera shifts towards the sun. For her diploma show, the footage was split into two films, but for this exhibition, she divided it into three. Thus, a single vertical film becomes three horizontal ones, and they move independently. By cutting the films, Laçi adds her own perspective to that of the person filming, referring to herself as “a second-hand observer”. Visitors of the work then add a third layer of reception. The work ultimately addresses questions of authorship and the power structures lying within the production of images.

I also noticed overlaps between the two practices in their physical form. Jonida’s originally vertical videos are divided into horizontal sections, while Luīze’s work Speech and Eulogy (2025) features in the same way, metal-framed segments on its reverse side. Could you tell us more about these works?

Hannah: Luīze painted new works – Speech and Eulogy (2025)– on-site that reference amateur marble replicas of two fireplaces in the house of the Kaudzīte brothers, and thus refers to Mērnieku laiki [The Times of the Land-Surveyors] (1879), the first novel written in Latvian. The process of translation, the roughness of it, and the visible materials—it reflects the idea of “dare” and exposing alternative knowledge.

The exhibition combines the concepts of physical movement, perception, and narrative.

Anna: Yes. Jonida’s work is specifically attentive to the conditions of presentation, like lighting, which can conflict between film and sculpture. Projections usually need a dark environment; sculptures need a rather bright one. The film installed along all the windows of the exhibition space, an element that was already part of Laçi’s diploma show, creates an environment that is neither perfectly dark nor perfectly lit.

She refers to the need to mediate between the diverging needs of the media she uses as “a strategy of compromise.”, while it also connects to her interest in exploring the possibilities of withdrawing something from view as a conceptual gesture. Beyond that, the foil creates a common framework and serves as a connecting element for the works of both artists.

It’s interesting because it parallels both her and Luīze’s approaches. Jonida engages with compromise and translation in the way images and projections are presented, while Luīze explores translation through research in a material and architectural sense. Together, these approaches create a broader conceptual overlap.

Hannah: For instance, normally, we’d never show a half-finished drywall in an exhibition or leave cables on the floor. But through discussion with both artists, we realized it was essential to their practices and accommodated it. Both artists are critically reflecting on the conditions of presenting work. Doing things in seemingly “imperfect” ways is a part of that reflection.

The publication, with texts by Mirela Baciak and Chris Clarke, will be available in December, communicating the theory and research behind the works and the artists’ practices more generally.

Kunsthalle Wien Prize 2025: Jonida Laçi and Luīze Nežberte

Opening: 6 November 2025, 7 p.m.

Duration: 7 November 2025 – 25 January 2026

Artist talk: 10 December 2025, 6 p.m.

Jonida Laçi and Luīze Nežberte in conversation with Anna Marckwald and Hannah Marynissen, curators of the Kunsthalle Wien Prize 2025

Address: Kunsthalle Wien Karlsplatz, Treitlstraße 2, 1040 Wien

Opening Times: Tuesday-Sunday 10:00-18:00, Thursday 10:00-20:00

More about the exhibition: www.kunsthallewien.at