As if it were to amplify the interaction between the space and the artworks, during my visit pouring rain started and transformed the window view over Linz in a greyish, unfocused, and blurring image that spontaneously engaged in a dialogue with the black-and-white videos inserted into the concrete sculptures.

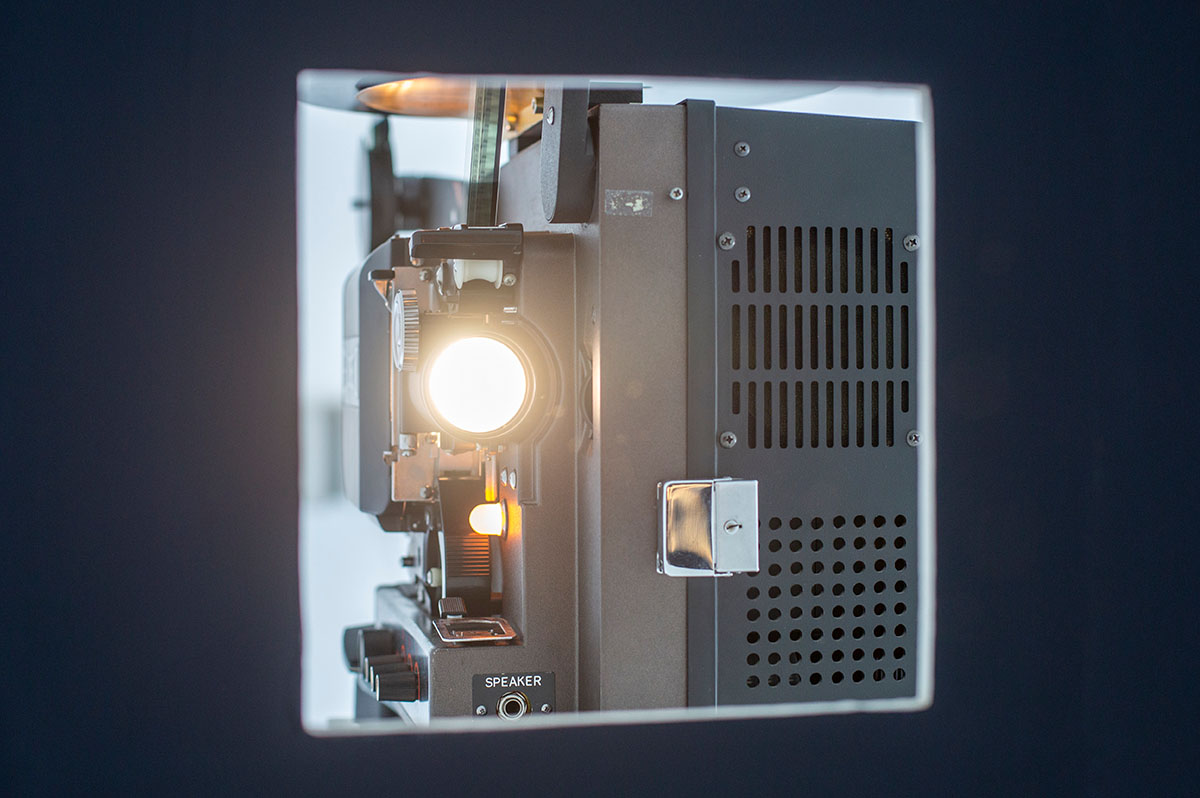

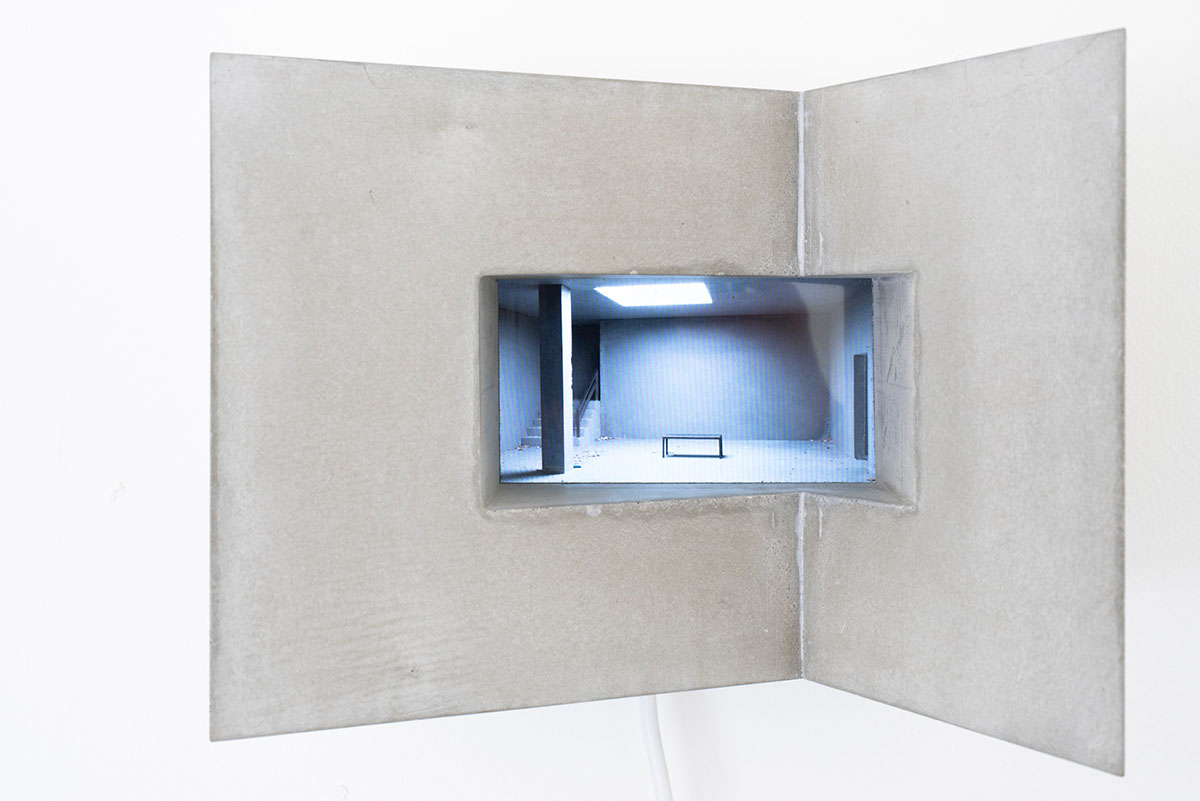

Bernd works with video in a way that one begins to perceive its fragility—overexploited, devalued medium suddenly unveils its sensual nature. Encased into solid structures, videos shimmer and ripple silently from within. Their fragile bodies are sheltered and protected, and to look at them one needs to come closer and almost sink into a cut-in window; the spectators immerse in every piece, for it is always you and the video, at a very intimate distance. In contrast to robust concrete forms, the embedded videos – soft and fluid – seem to be lapping inside. This association with liquid is also suggested by a dwell-like cut of some objects, inside which the videos are placed as if they were poured in; or by the tube-like cables connecting the sculptures on the wall as if the videos circulated within.

Some of them one can see only reflected in the built-in mirrors. Oppl makes the spectators feel the medium as a flowing, sensitive, changeable material.

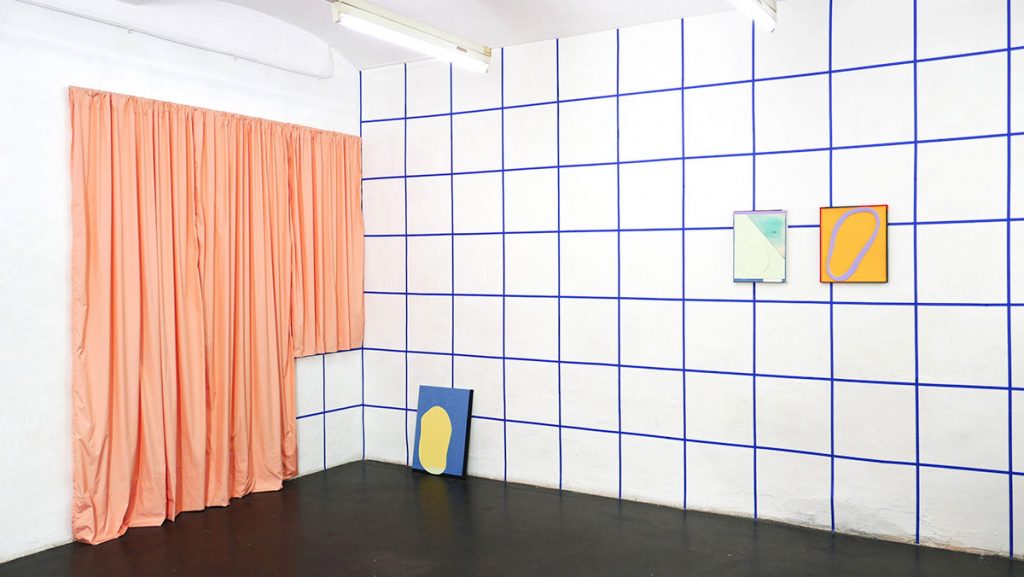

Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz

Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz

Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz

Every video screen is also rather small. Overwhelmed by huge-scale visuals, when our gaze encounters imagery of a smartphone size, it soothes – there is a feeling of privacy and security to it. And it is not only a symptom of sensory overload in digital realm, because the most precious images have always been small. For instance, locket pendant necklaces for carrying a miniature portrait of a beloved person that were meant to be taken out and looked at privately. Or another example from my post-soviet childhood – the game Secretiki or Skyskope. For it we would dig small holes in the ground, somewhere in a backyard or any other secluded place, usually under a bush, so the spot wouldn’t be easy reachable, then we would create tiny compositions of flowers, beads, leftover foils and wrappings, cover them up with a piece of glass and finally bury carefully. Secretiki (meaning ‘secrets’ in Russian) used to be our hidden treasures which we revisited during the season – regularly we would come to unearth them and look at the small designs preserved under the glass. As a secret thing, they were shown only to the dearest friends so to enjoy them together. Surprisingly, Bernd’s project evoked in me this forgotten excitement of re-discovering a secretik. And that made me think that these thickly coated, with only a peep-window left, silent videos might be some personal memories or secret fantasies.

bernd oppl

bernd oppl

bernd oppl

However, the footage is alienated, it could be made by a CCTV camera – cold, distanced, static. And there is a conflict. One anticipates seeing something intimate but faces, on the contrary, something estranged and obscure. Abandoned, deserted places. For example, on one video you observe an empty room with a bench in the middle lit by a white light from above, there are some scattered dry leaves mixed with garbage on the floor, wind comes and stirs it all, then goes and everything settles down back – a repetitive action leaving you with anxiety. Perhaps, Oppl shows us recollections of a machine. Of the technological gaze operating without human intervention, of a functioning video camera mesmerizing by its indifference and resiliency… Although the original rooms are hand-created dioramas, they just intensify the strange feeling of dissociation. The camera here is the protagonist, it is controlling and exposing, monitoring and examining, and simultaneously daydreaming—it is creating its own secretiki somewhere at the fringe, in the peripheries of the digital world.

If back in my childhood, we were playing the Skyskope gamein a world of undeveloped media with its scarce influence on our imagination, then Bernd constructs it in the absolutely different situation of a total media presence. He interprets the technology as being capable of creating hidden places for memories of its own and introduces us to the tech-poetical visions of video cameras (turned on and surveilling 24/7). The artist even organizes an immediate encountering with the technologic memory – in the installation Screening Room, the spectator peeps into a diorama of an empty cinema theatre and after a while their face appears on the screen.

bernd oppl

bernd oppl

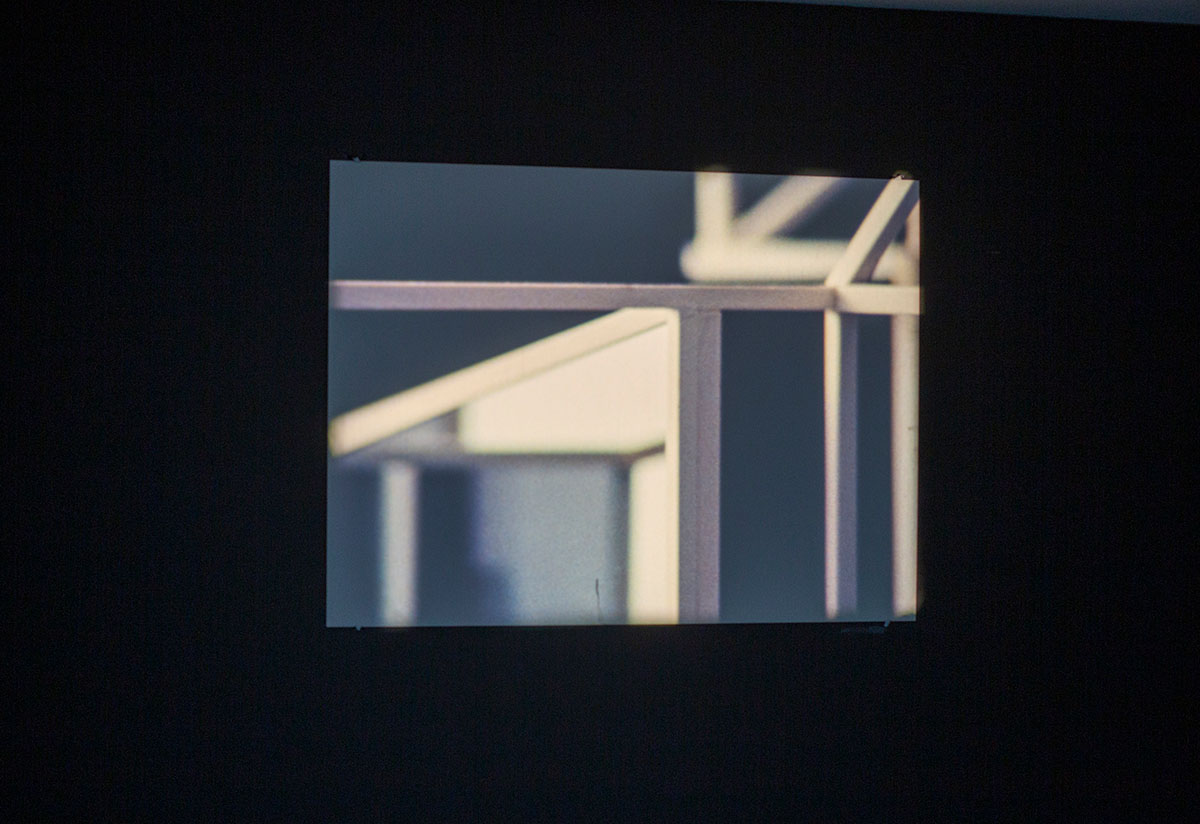

The central piece of the show is the 16mm film Hidden Rooms (2021), in which the sliding camera is documenting a structure resembling a house. Slowly rotating, penetrating, gliding along and out, it demonstrates the object in a hypnotical way, like an endless white pattern against the black background. Hidden Rooms made me think of Ballet Mécanique (1924) by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy (which had been also originally demonstrated without tone). In Bernd’s film, the model of the house is slowly disintegrating and dissolving into an abstract form – the camera movements are taking it apart and re-assembling anew. Spellbound by the meditative slide, the gaze is fully managed by the camera and while following it, loses the idea of the whole thing.

To sum it up, Bernd Oppl’s exhibition reflects on politics and poetics of the gaze within totality of media. The artist researches how the gaze is captured, guided and supervised by technology; at the same time he delves into the imagery produced by technology and explores its sensibility, capacity for creating new territories of emotional experience. The ambivalence – of revealing and concealing at the same time – creates a porous environment where every outward movement becomes an inward one, and vice versa.

Bernd Oppl – www.berndoppl.net

About the writer: Liudmila Kirsanova is an independent curator and writer, whose research is focused on autofictions, storytelling, and politics of belonging. In 2019 she became the finalist of the curatorial award Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm. Curating international and domestic projects, Kirsanova has been advocating and promoting female artists, in particular those from non-Western cultures.