Your solo exhibition „The Line We Cross“ is currently on view at Living Room in Athens. How did this come about? Where did you first meet Auðunn and Nikoletta?

Marlene: I spent the first three months of 2025 in Athens for a residency based in Kypseli. An incredibly vibrant neighbourhood full of self-organized art spaces, collective initiatives, and artistic gems. It’s one of those areas where you naturally end up meeting people who share your energy. A mutual friend introduced me to Auðunn and Nikoletta, and we immediately clicked. We connected not only on a personal level but also through a shared interest in collective practices and a genuine curiosity about each other’s work. The space was still located in Kypseli, so we were practically neighbours throughout my residency. After seeing how my work developed during those months, Auðunn invited me to present a solo exhibition – one of the first positions in Living Room’s new location – which ultimately led to “The Line We Cross.”

Could you tell me about the founding of Living Room? What was your vision? How has it evolved over the years?

Auðunn: I never really set out to run something like Living Room before. It happened quite organically. It started in my living room in 2022. I didn’t have a studio to work on my art, so I thought I’d make an exhibition at home and invite people over for an exhibition opening disguised as a house party. I never ended up showing my own work; in the end, I asked other people to exhibit. I liked the idea of a house party/exhibition opening, so I had a couple of these events at my apartment, with an exhibition in the living room. In 2023, I came across a cheap commercial space in Kypseli and thought I’d rent it as a studio for myself. As I was renovating this space, ASFA went on a strike, and all the Erasmus students lost their studio access. I thought I’d offer my space for little pop-up exhibitions while I finished renovating it, since I had enjoyed curating these exhibitions in my living room before. I needed a name for the space and thought it would be funny to keep it, given that this new space was obviously not a living room. It started snowballing from there – people began approaching me and submitting exhibition proposals. I liked how it seemed to be organically turning into a gallery/project space. I never had a clear vision; I described it as an artist-run project space. In 2024, I decided to invite five Icelandic artists to exhibit and began to curate the exhibitions and program more carefully. Nikoletta joined me in organizing and curating around this time, and we worked well together; it became easier to expand the scope of the exhibitions a bit.

In 2025, we had to move out of our space in Kypseli due to increased rental prices, but this coincided with the same time that another gallery, One Minute Space, run by Nadja Geer, was closing. Nadja didn’t want her space to go to waste, so we came up with a plan that could keep Living Room running and make use of her space. There are six studio spaces at the new location in Metaxourgeio, in addition to the gallery itself.

Was it difficult to find an exhibition space in Athens?

Auðunn: In my case, no. I was fortunate with the Kypseli space – I walked past the space one day and noticed that there was a new sticker in the window, saying it was available for rent. I thought the space looked good, and I had been thinking about renting a studio for myself for a while, without giving it much serious thought, so I gave the number on the sticker a call. I think it was the day after that I met with the real estate agent in the space, and he said there was already an offer for the space, so I decided to just go for it. The same fortune carried us to the current space in Metaxourgeio – we were lucky that the closing of One Minute Space coincided with us losing the Kypseli space, and that we were able to take over the rental contract without the space going back on the rental market. However, prices for commercial spaces for rent seem to be skyrocketing in some areas (notably in Kypseli), so these spaces are becoming more difficult to come by, unfortunately. I’ve noticed other project spaces losing their accommodation due to increased rent, and those that stick around usually have a similar story as I do – some mix of luck and great timing.

What does Living Room mean to you? How does it inform the concept of the exhibitions?

Nikoletta: Living Room, funnily enough, often feels like a big corner couch with huge pillows where you meet friends for some tea on a Saturday morning after a long week. It’s essential to have a space that is comfortable and safe enough for artists to express their ideas freely. So, being able to provide that to the artistic community in Athens leaves me more than greatly satisfied and fulfilled. When artists manage to move any barrier they might have, and test themselves, try out something new, share maybe a crazy vision of theirs with us and then we try to realize it together, that is for me a win, a goal any art space or gallery should care to achieve. This tendency of ours often leads to an even more intimate collaboration with the artists; our texts and curation don’t feel stiff or unapproachable, and people visiting our exhibitions say they feel warm and inviting, as they have also kindly shared with us during Marlene’s opening. What is a space for art even for, if not for evoking people’s freedom and creativity?

Living Room has also helped me personally evolve as an arts professional, providing this care and freedom to me as well to test, correct and optimize my knowledge while also always gaining new ones. I am very grateful for all the amazing people I have met through our collaborations and at openings. It’s very heart-warming seeing a community forming around a sincere endeavour like Living Room and getting stronger and ever more supportive as time passes.

What does the process mean to you? How has the space influenced the development of your work?

Marlene: One of the things we connected over right from the start was the idea that Living Room isn’t just an exhibition venue. It’s a space where artists can work, experiment, and develop new artworks on site. That immediately resonated with me, because I’m deeply interested in how artistic processes shape curatorial decisions. My master’s degree, „When Artists Curate: From the Studio to the Exhibition Space,“ explored exactly that: how artists use the studio as an exhibition environment and how this influences the way shows are conceptualized. Working this way enables a much more meaningful and sustainable collaboration between curator and artist. It’s not a conveyor-belt approach to exhibitions; it’s an in-depth, shared exploration of the work. Having almost four weeks in the space before the opening meant we could rethink how to hang the pieces, develop the publication texts together, and – I didn’t expect this – delve into creative writing and create an entirely new installation on site.

As artists, we’re rarely given the chance to work in a generous, light-filled space without tight financial or time pressure. That freedom allowed the work to unfold with a different kind of calm and conceptual depth, and the exhibition truly grew out of that process.

The red thread appears frequently in your paintings. What does this motif mean to you?

Marlene: The red thread has become a kind of recurring companion in my work: sometimes I joke that it follows me rather than the other way around. It appears in my paintings and embroidery, and I even have it tattooed on my arm. For a long time, I didn’t question it, until I realized it was tied to something deeply personal: the red-on-white embroidered tablecloths and pillowcases my grandmother made. That memory opened up a whole lineage of women whose work shaped the spaces I grew up in, often through gestures that were caring, repetitive, and rarely acknowledged.

For me, the red thread is both material and symbolic. It’s a connector and a boundary, a line that can join things or hold them apart. Working with stitching led me to think about domestic craft and how it occupies this interesting space between decoration and labour, visibility, and invisibility. In Austria, embroidery is part of a cultural heritage, yet it has also been historically tied to gendered expectations—women adding beauty and care without necessarily being granted authorship. When I use the red thread today, it’s not about nostalgia. It’s a way of engaging with that complexity. Painting and embroidery feel like parallel forms of storytelling: slow, rhythmic processes that allow me to reflect on relationships, both on a personal and on a global scale. The red line becomes a language of connection – across generations, across spaces, and within the communities I move through. In a sense, following that thread helps me ask questions about labour, care, history, and how something as simple as a line can carry so much meaning.

How would you interpret Marlene’s work in a social context?

Auðunn: I interpret Marlene’s work as a meditation on how we become social beings through our encounters with others. Her works gather in an abstract, undefined space, where bodies negotiate closeness, vulnerability, and the desire to connect. The scenes echo how social life unfolds at every scale: from intimate gestures of recognition to the larger movements of collective and political bodies. The red thread that runs through the work plays with this tension, both celebratory and cautionary, suggesting both the joy of finding one another and the need for boundaries within shared spaces. In this sense, Marlene’s work doesn’t just depict people together; it stages the processes through which identities are shaped, relations are tangled and untangled, and a sense of ‘we’ emerges. It asks where the line between us lies, and whether that line is something we draw, cross, or continuously remake together.

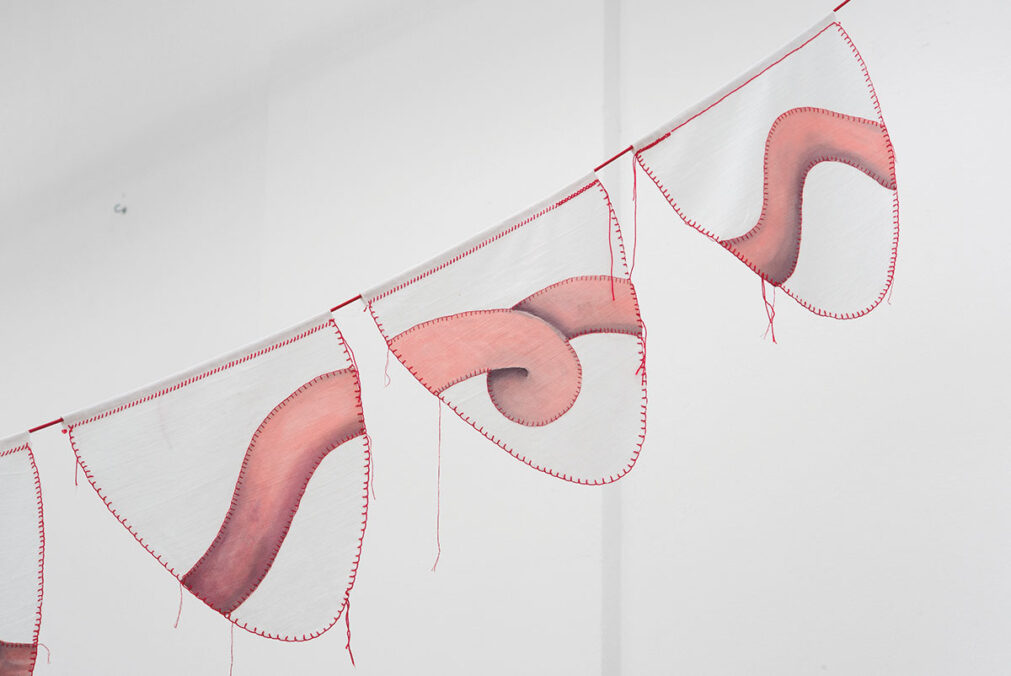

Could you tell me more about the work „hanging by a thread”?

Nikoletta: It is a central piece in the exhibition, and there’s a fair reason for that. Seven fragments of embroidery canvas cut in the shape of party flags run across the edge of ‘Play Nice’ in the center of the space to the wall on the right through a red rope. Painted on separate canvas and stitched onto the flags, the looped arms stretch to find one another in the middle flag. Yet they do not touch. Did they actually see each other? What would happen if they did?

This work combines all of Marlene’s narratives in the most ingenious way. The flags call for a celebration, and the stitching evokes a shared tradition. The arms behaving in this uncanny manner imitate the thread’s own manner, exactly like people moving forward, changing their minds, going in circles, and getting confused in difficult situations and still reaching out, though, for each other. And we always do, that’s what’s beautiful with us humans. It’s amazing how Marlene managed to capture all of these subtle realities in one piece.

Which types of artistic approaches are you interested in at the moment?

Nikoletta: I find socially engaged practices very intriguing, whether that be in the form of fieldwork, or a participatory performance, or so on. When artists engage with their environment and community, amazing things can occur. They can discover brand new material for their own practice in the process and share a very genuine outcome. And that’s something we encourage when artists are interested in doing something like that. The same intertwining goes for mediums when paintings, sculptures, found objects, and sound pieces become a concentrated installation which can only exist in that way in the specific time and space for which it was created. I like seeing artists challenging limits and terminologies. I have a soft spot for ecofeminism, and seeing natural elements of any sort embodied in artistic practices always draws me in. In general, I value a lot of art as research.

How do you select the artists for Living Room? How important is international exchange for you?

Auðunn: The process of finding artists is partly from submissions and partly from networking. A lot of the exhibitions are by artists who visit our exhibitions and attend our openings. We don’t really look at academic backgrounds or how extensively artists have exhibited in the past – if we like the work, then we’ll invite the artist. International exchange has always been a focus point. As a foreigner in Athens and having lived as an artist in other countries in the past, I’m familiar with the struggle of getting your work exhibited in a new scene. I enjoy being able to provide this platform for international artists. We have made great efforts to also establish a Greek following and collaborations, so that we’re not just a group of foreigners showing other foreigners works of foreigners, not engaging with the local community at all.

As part of the exhibitions, a book is also published. What role do publications and editions play? Where can they be purchased?

Nikoletta: Transforming parts of an exhibition physically in the form of a publication certainly allows the exhibition to live on and helps maintain the memory of the information and the feeling shared through an exhibition. In a way, it makes it more ‘real’, doesn’t it? When you can hold in your hands the ideas of the people who worked on a project, long after the show is over. Reliving the experience of an exhibition by just flipping through a catalogue, for example, is a valuable advantage in print culture, and don’t mind the romantic historian in me saying that it is also a useful addition to the contemporary art history mosaic.

We have been anticipating making a publication alongside an exhibition for a very long time, and we are very excited that it has finally happened. On the occasion of Marlene’s exhibition, The Line We Cross, we published a book sharing the same title, and we wrote three essays using the exhibition as a starting point and elaborating more on some of Marlene’s topics, making the book stand on its own and beyond the gallery space. Marlene’s essay ‘scratching the stitch’ works as a testimony of her stitching practice and the connections with the traditional Austrian embroidery, Audunn’s essay ‘connection is as simple as bodies finding each other in space’ focuses on how people as physical forms interact with each other and their surroundings, and mine, ‘a red thread unfolding…’ is an intercultural introspective on the history of the red thread and its connotations in human relations. The texts are accompanied by photos of Marlene’s artworks, making the book also function as a catalogue of the exhibition. People can still purchase it in the gallery and through our social media for as long as the exhibition is running, and we’re currently talking to a certain bookstore that was interested in carrying the book after the end of the exhibition.

What experiences or insights have you gained during your time at Living Room?

Marlene: It’s always a bit tricky to reflect on an experience that’s still unfolding—I usually understand things better in hindsight. However, I can say that I’m especially moved by everything we did to let this exhibition live beyond the moment the paintings are on the wall. I’m genuinely proud of our publication and the texts we developed together. They didn’t just add depth to the exhibition; they also gave me the chance to articulate my thoughts in a register that differs from the visual one. And in a way, they allow the project to continue existing long after the show closes. I also feel that the slow-paced, sustainable approach at Living Room significantly advanced my practice forward in a very real way. It encouraged me to challenge myself technically and to bring in other forms of making, such as stitching and textile work. I’ve grown beyond the frame of the canvas, and I’m excited to see how these developments will unfold in future projects and how the works will be received once I bring them back to Austria.

I’m someone who often feels the pressure to constantly produce – new works, new posts, new stories, new everything – in a world that sometimes feels like it’s endlessly hungry for content. It has been incredibly refreshing to work on something so intentionally sustainable. The process gave me space, time, and support, and it allowed me to connect with wonderful curators and art professionals (like both of the curators, or our photographer, Frank Holbein), whom I look forward to collaborating with again. This has been a rare experience where the work, the relationships, and the pace all felt aligned.

Solo exhibition: Marlene Heidinger – The Line We Cross

Curated by: Auðunn Kvaran and Nikoletta Georgakopoulou

Exhibition duration: until November 23rd

Address and contact:

Living Room

Marathonos 71, 104 33 Metaxourgeio

www.livingroomathens.com

Living Room is an independent project space currently situated in the Metaxourgeio district of Athens, Greece. Founded by Auðunn Kvaran, the space is currently managed by Auðunn and Nikoletta Georgakopoulou. Living Room is dedicated to fostering the creative development and public presentation of contemporary art. The project space offers a supportive environment for artists to realize their artistic concepts, from initial ideation through to the final exhibition and potential publication. Each artist’s engagement with Living Room is conceived as a focused, short-term residency culminating in a public exhibition of their work. A key objective of Living Room is to serve as a valuable platform for international artists seeking to exhibit their work within Greece, thereby facilitating the expansion of their professional networks beyond their domestic art scenes. Living Room places a particular emphasis on hosting artists‘ inaugural solo exhibitions in Greece or their first solo presentations outside of their countries of origin. Through this focus, Living Room aims to cultivate meaningful dialogue and exchange between disparate artistic communities, offering a unique opportunity for artists to gain international exposure and critical recognition.

Auðunn Kvaran (b. 1995, Reykjavík) is an Icelandic artist and curator. He graduated with a BA degree in Fine Arts from the Icelandic University of the Arts in 2020. Following graduation, Auðunn exhibited extensively for the first year, then took a hiatus and relocated to Athens, Greece. In Athens, Auðunn subsequently founded Living Room, a venture best described as a project space, artist-run space, or off-space. Currently, Auðunn’s engagement with the art world is predominantly curatorial and primarily through Living Room. Auðunn continues to create art and generally exhibits by invitation. Auðunn’s artistic practice involves replicating elements from the environment, manifesting these as sculptures, sometimes incorporating found materials, or translating them into 3D models, which are then integrated into recorded videos. Sentences from personal journals may also be incorporated into these video works. The resulting pieces can function as a form of visual journal; however, Auðunn prefers these not to be overly specific to himself, to allow for broader viewer reflection and connection. The artworks are not intended to solve problems or propose strong statements. Rather, the aim is to create pieces that reflect observations from Auðunn’s own life, presented in a manner that allows others to find relatable aspects within their own experiences. Auðunn’s art practice generally avoids overtly political themes, although it is acknowledged that political factors will inevitably influence the artworks, an inescapable aspect of creative expression. www.instagram.com/audunnaudunnaudunnaudunnaudunn/

Nikoletta Georgakopoulou (b. 1996) is a Greek curator, artist, and writer. She studied Theory and History of Art at the Athens School of Fine Arts and has attended numerous seminars in performance, physical theatre, and photography. Her multidisciplinary work meditates on the ecological and feminine, often posing open-ended questions and reflections on the human condition. Through performance, installation, photography, digital manipulation, and text, she delves into the notions of time and the tenderness of the senses, drawing inspiration from the realm of nature and its intimate connections to femininity. Concepts needed to be communicated are proceeding the demands of each medium, so she often enjoys stretching her limits. Her curatorial work focuses on fostering meaningful exchanges between artists and audiences, while also emphasizing artist-curator collaboration and the social resonances of contemporary art. She has curated and supported exhibitions that foreground dialogue, care, and collective vision, while highlighting the unique voices of each artist. She also curates and writes for independent projects, collaborates closely with artists on portfolio/proposal editing, and well as conceptual guidance. www.instagram.com/nikolettageorgakopoulou/

Marlene Heidinger (b. 1996, Vienna) is a painter, curator, and filmmaker based in Vienna, Austria. She pursued studies in painting and experimental animation at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and the École de Communication Visuelle in Paris. In June 2024, she earned her master’s degree in Curatorial Studies (“/ecm”) from the University of Applied Arts Vienna. Her master’s thesis, “When Artists Curate: From the Studio to the Exhibition Space,” explored curatorial strategies employed by artists, focusing on the use of the studio as an exhibition space. This work reflects her broader interest in curating as an extension of artistic practice. Her work explores connection, care, and the shifting boundaries between individuals and collectives. Through material experimentation and layered storytelling, she examines how bonds are formed, maintained, and undone. www.instagram.com/marlene_heidinger/