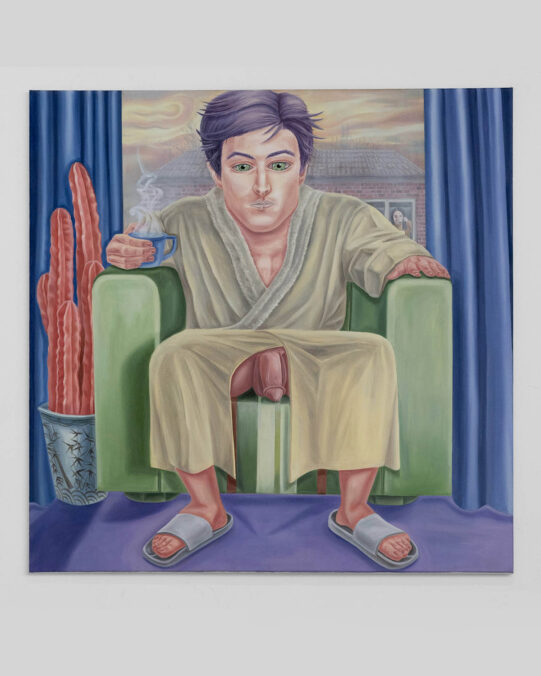

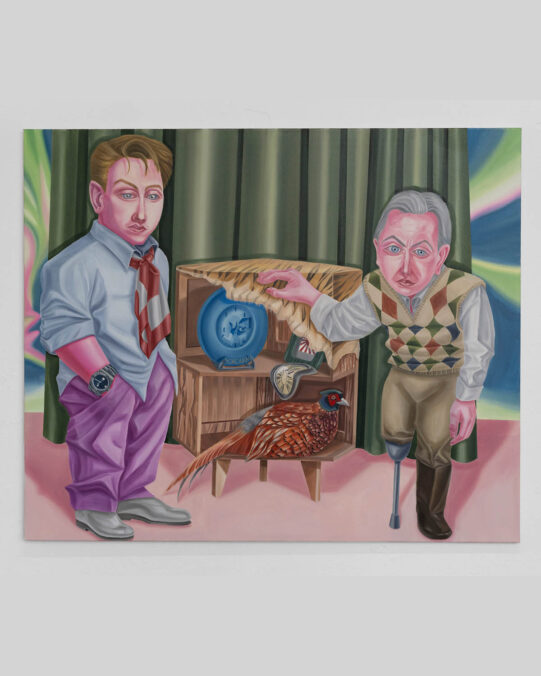

Inae Shin, born in South Korea, lives and works in Hamburg. She is currently studying painting at the University of Fine Arts Hamburg (HFBK) in the class of Anselm Reyle. Her work explores ambivalence in Emotions within human relationships, such as intimacy and distance, care and control, stability and unease. Through layered imagery, she examines how these opposing feelings coexist and form subtle power structures.

How has living in Hamburg influenced your themes?

Since I’ve been living in Hamburg, I’ve started to spend time alone and observing my surroundings. The city’s frequent cloudy days and quiet vibe have made my work more reserved, while emotions are expressed more intensely. I feel that more space has been created in the characters and relationships in my paintings. Hamburg has become a stage that creates tension, silence, and emptiness in my works.

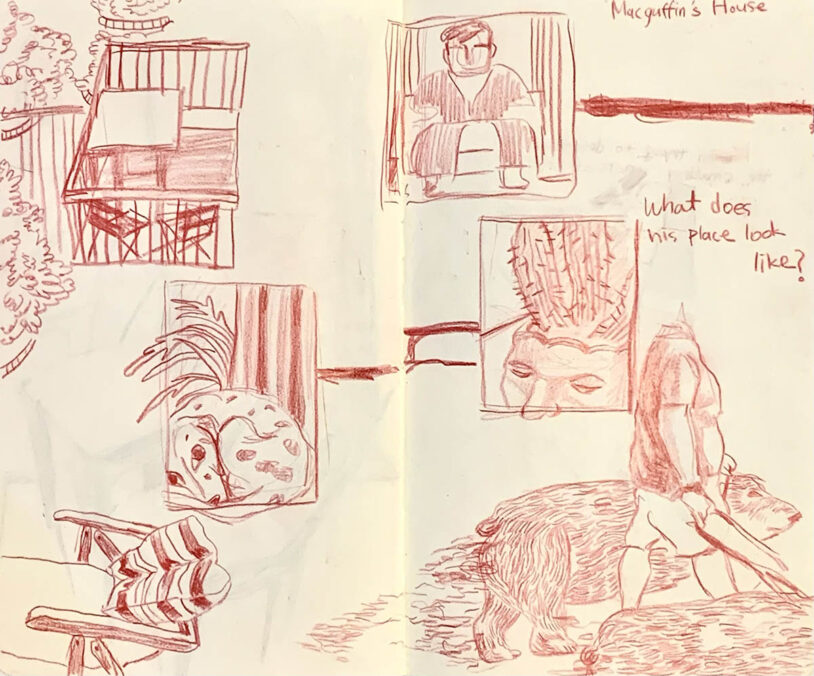

How do you typically begin a new artwork?

I find ideas in my diaries or in the novels I read. I write down phrases that stay with me and reflect on them for several days. I am not translating text directly into paintings. I approach it by asking painterly questions, for example, “What hat color would this character have? What kind of space would the silence in this sentence create?” During this process, my feelings are intertwined with the work, and so I build compositions and motifs in the painting.

Do you work on multiple canvases simultaneously?

I used to work on several paintings at the same time, but I stopped doing that. I realized that focusing on a single painting at a time results in stronger work.

How do you approach the balance between intimacy and distance in your paintings?

I try to observe what creates a sense of intimacy or distance for me in everyday life. I pay attention to subtle hand movements, eye shifts, facial tension, and gestures that hesitate between reason and emotion. Intimacy is expressed through the body and gestures, while distance is shaped through color and space. Some areas are intentionally brought closer, while others are left unresolved. I believe this tension is what holds the balance in my paintings.

Can you share the idea behind your work, Hands?

At the time, I was thinking about how to express the complexity of relationships without directly painting faces. Faces immediately suggest narrative and psychology, but the complexity I experience in relationships feels more rooted in the unconscious. Hands are the closest part of the body that can reach another person, yet they are also a place where contact often fails. In that sense, hands felt like the most honest language to me. I painted the hands in cold blue tones to remove emotion, while the intense red background represents the quiet but powerful tension between the two figures.

How do you view your art in relation to society today?

I feel that we live in a society where intimacy is gradually disappearing. Contemporary society appears highly connected, yet it contains a great deal of distance and isolation. Rather than directly criticizing this condition, my work approaches it quietly through bodies, gestures, and the spaces between gazes. I see this slow and restrained attitude as my way of relating to contemporary society.

Outside of art, what do you enjoy in everyday life?

I love reading books and watching films. Recently, I’ve been reading Fin by the Korean novelist Wi Su-jeong, and I found myself deeply involved in the characters. I also go running once a week until I’m completely out of breath. I want to build physical strength to sustain my painting practice.

Do you already have any plans for 2026?

I’m currently preparing for the annual exhibition and developing several new works. And in February, I will also participate in a group exhibition at Raum Linksrechts in Hamburg. This show is organized with fellow painting students from my university, so I’d be happy if you have the chance to visit.

Inae Shin – www.instagram.com/hwagashin/