What role does analogue photography play in your work?

As in the medium itself, a deeply great one. Its organic and unique feel makes you devoted to photography. Its ability to let you draw a photographic scene in your head before you can test-shoot and see it immediately is remarkable.

Why do you still choose this medium today?

It’s the slow progress of work. The limitation that makes it valuable. It’s better to go out with one 36-frame can and try to get the best out of it, rather than having endless digital opportunities. And looking through the prism viewfinder of a medium format camera is totally soulful.

Is there a particular atmosphere you are always searching for?

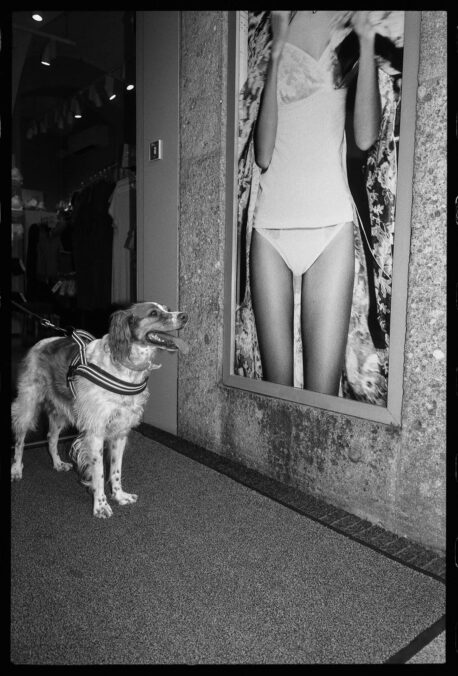

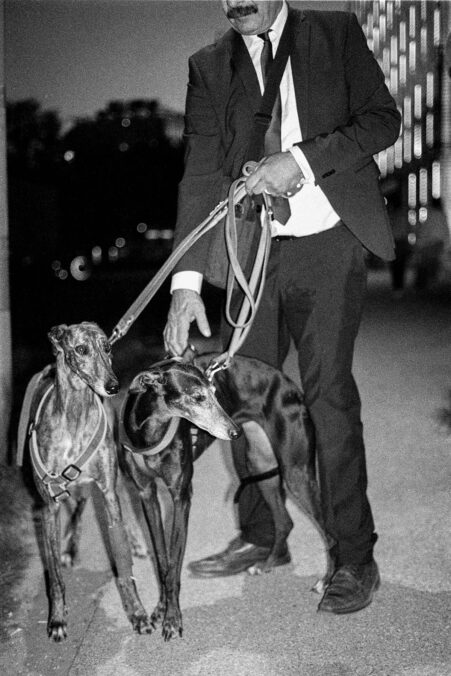

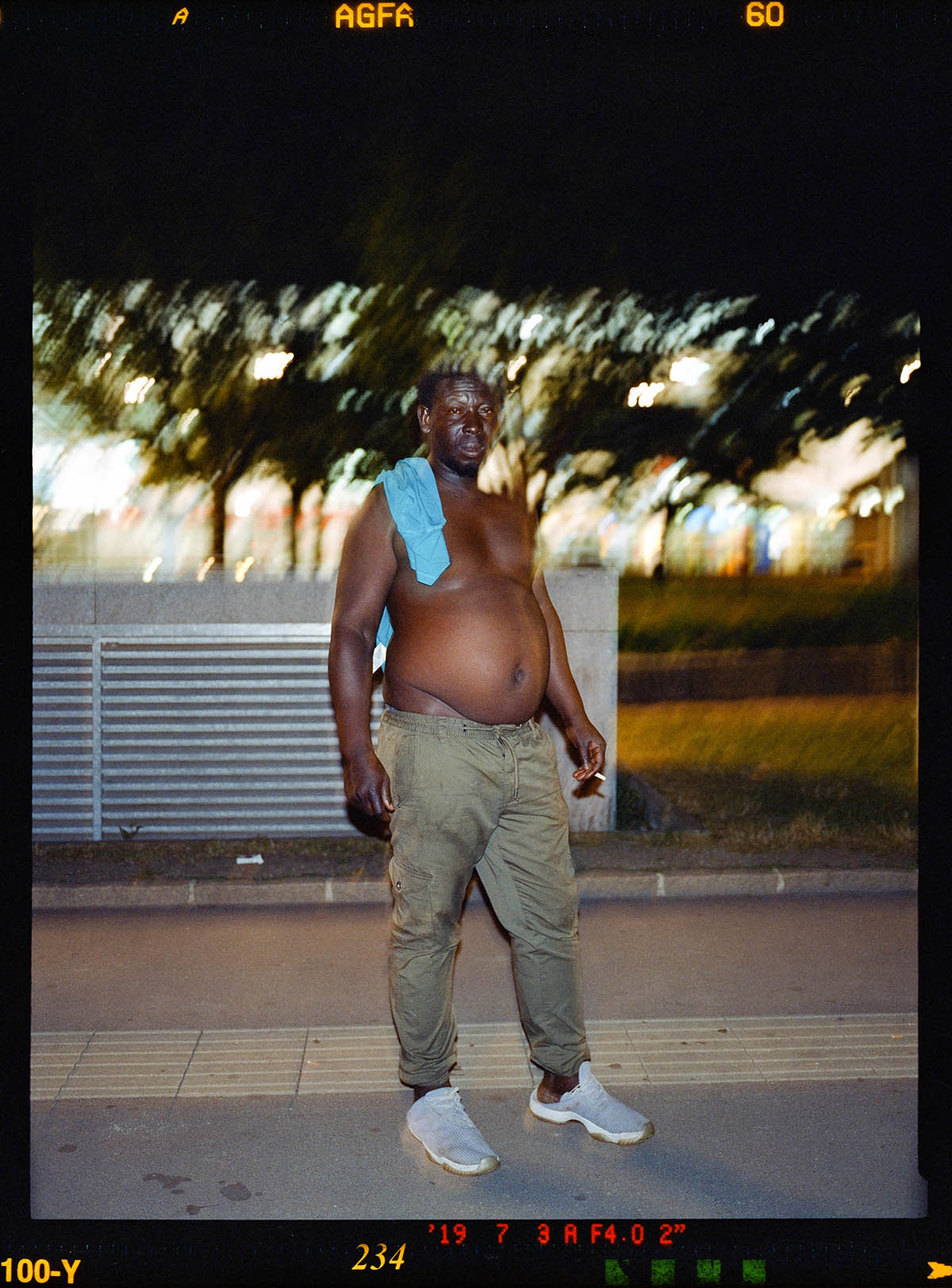

Capturing in the streets, I would rather have a chaotic crowd so I can be undetected and the people are unaffected by the camera. Taking portraits with a person, however, I really enjoy the silence around me.

How do you approach the people you photograph? Do you engage with them directly, or do you prefer to remain more of an observer?

It really depends on the situation. In some moments, people don’t want to be disturbed, and I can feel that. That’s when I must work quickly. I decide which perspective I want to shoot from, move in, and press the shutter. Usually, I follow it with a smile and move on. Everything that happens after that is another story, but often you can sense what’s about to happen. Sometimes, though, you just must accept that capturing a photo might provoke an uncomfortable reaction.

Do you see photography more as a way of documenting reality, or as a form of artistic interpretation?

The answer lies within itself: documenting reality with one’s artistic interpretation. Matter of fact, “reality” is to be described artistically or philosophically, not scientifically or politically.

How does photography change the way we look at the world?

It is a freedom of expression, which leads to innovations and the growth of a society. Photography, especially, can open “new worlds” of reality to the viewer, in its genuine and pure form.

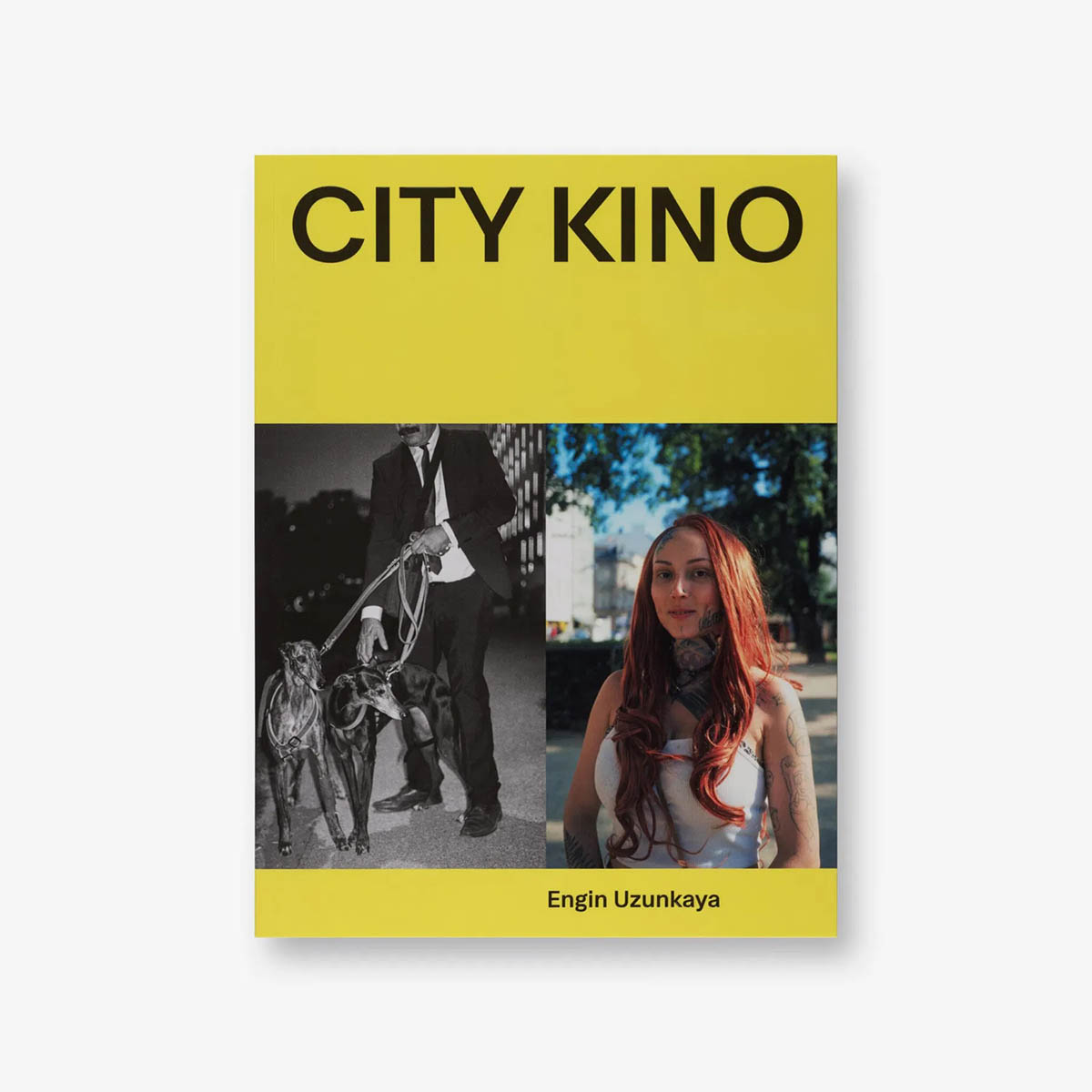

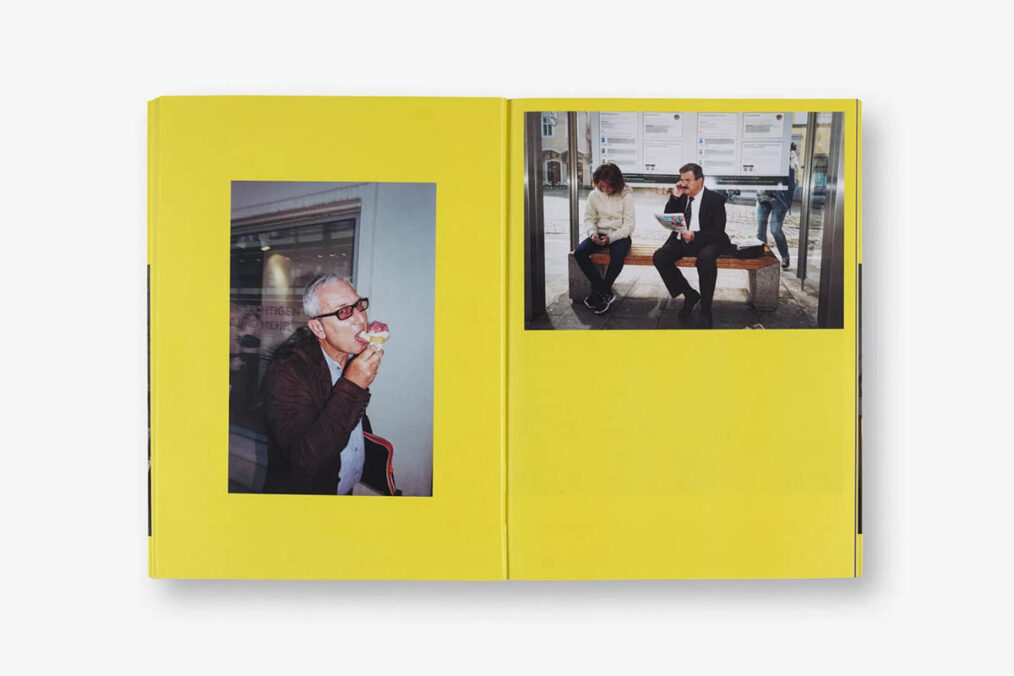

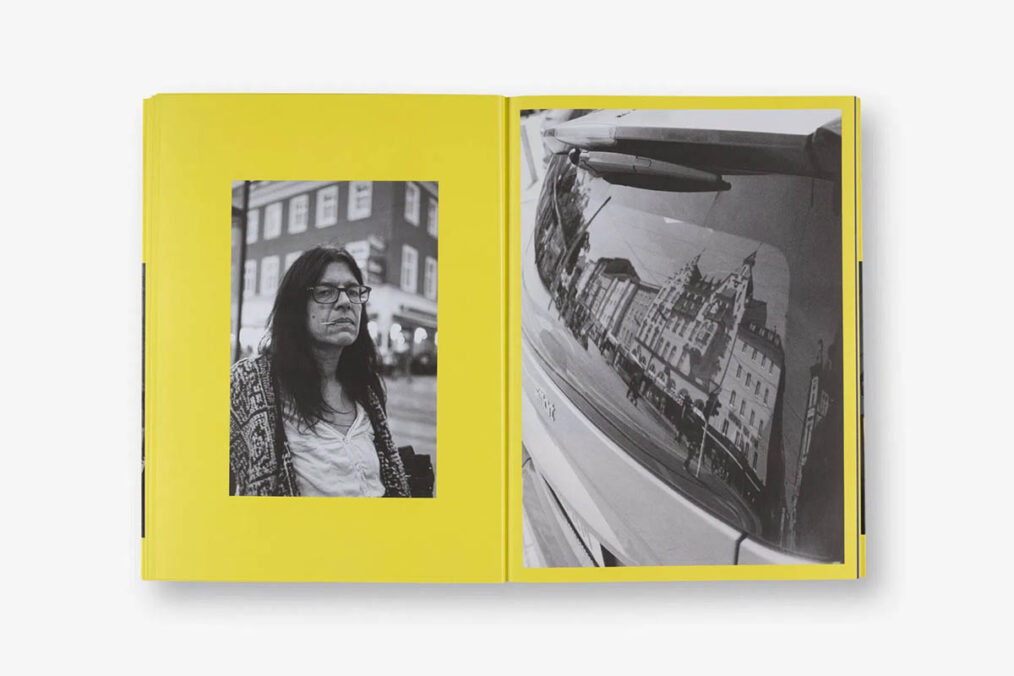

In 2025, you published the photobook City Kino. How did the idea come about?

In 2020, I printed a 290-page book titled “Come and See.” It was part of my bachelor’s thesis, completed shortly after a very critical surgery from which I narrowly escaped death. For me, photographs in a book always carry much more value and evoke a different feeling than seeing them only digitally. For City Kino, an employee of the Lentos Kunstmuseum suggested that I reach out to the publisher Fotohof. I initially sent them a digital version, and that’s how the publication came to be.

How did you decide which images to include in the final selection?

For the most part, I did it together with the publishing house. We sat down and went through the pictures; thousands of them. The main idea was to create a series about the everyday lives of the people I had captured.

Were there photographs you decided not to include because they felt too intimate?

Not really, and I want to point out that photographers, to a certain degree, can know what is morally right or not.

Are there particular places in the city where you enjoy spending time?

Parks, Turkish grocery stores, Balkanic bistros, Sami’s place, or thrift stores. I like the northern part of Linz after the bridge, which is the “Urfahr” district. Its streets have more trees than an average park in the center of Linz. Unfortunately, the old classic image of Linz is fading away and being replaced by ugly concrete architecture.

Finally, where can readers check and buy the book?

At www.fotohof.at

Engin Uzunkaya – www.enginuzunkaya.com, www.instagram.com/engin.uzunkaya/