Until recently, we all knew him as Kid Cudi. Today, it is under the name Scotty Ramon that he presents his first solo show, ECHOES OF THE PAST, at Ruttkowski;68 in Paris.

He enters the gallery with a radiant smile, greets everyone, and then begins to speak about his practice. The atmosphere is quiet, suspended, almost prayer-like — the setting in which he explains why, after turning forty, he felt the need to change direction. He was looking for something to take his mind off things when, just over a year ago, he decided to buy some paint and some canvases and give it a try. He immediately understood that painting had a therapeutic effect on him and chose to dive in headfirst. From the very beginning, he proved to be extremely prolific, producing three or four works a day. The recurring theme is self-destruction, approached through really bright and upbeat colours, deliberately chosen to betray our expectations. It is the same trap he once set for us when we sang along to the psychedelic lullaby Pursuit of Happiness or danced to the Crookers remix of Day ’n’ Nite, without fully grasping the frustration and paranoia beneath the surface.

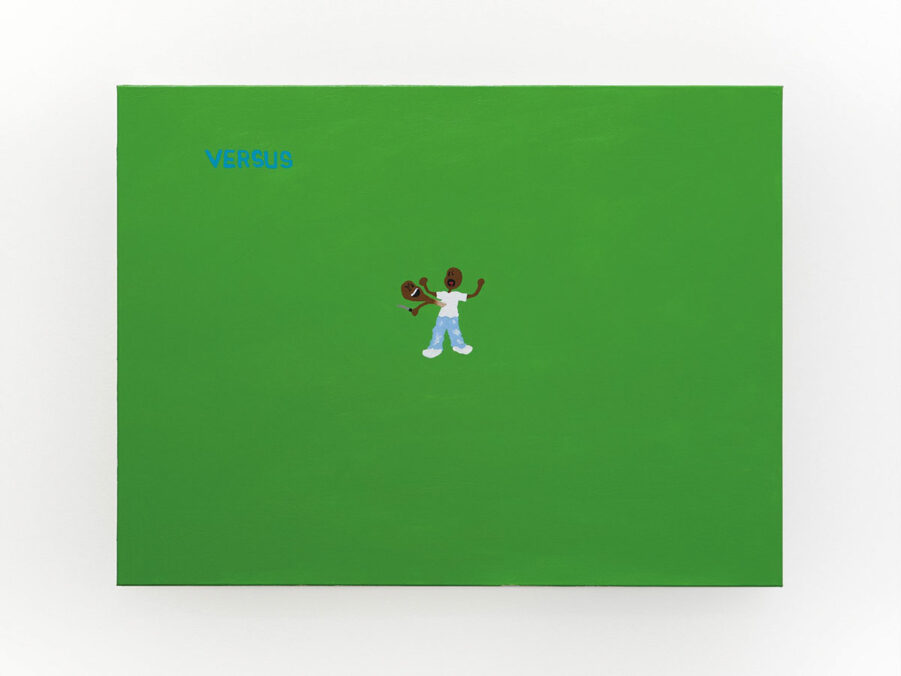

He recalls his first painting: once finished, he stepped back to focus on it and thought, “What the fuck is wrong with me?”. At the centre, swallowed by a shocking pink background, stands a tiny character named Max. Wearing jeans and brand-new white sneakers, he is slitting his own throat. A different imagery, yet a similar tension, emerges in VERSUS #2 SABOTAGE, hung nearby. Once again, Max is a victim of himself, immersed in an acidic green. Like an appendix piercing his stomach, a maimed spirit threatens him with a single arm holding a knife. VERSUS is not only a painting but also a sculpture, born from the desire to create a personal version of his friend Kaws’ Companion.

Max is not merely an alter ego, but rather his inner child: something that seems to have gone away, yet is always ready to return whenever Scotty Ramon needs it. Painting becomes a way to return to childhood, to rediscover a sense of freedom and lightness often lost with age. His studio turns into a bedroom: a place to retreat, to be alone. And it is precisely in that bedroom that, until the age of sixteen, Scotty Ramon dreamed of becoming a cartoonist. These roots are clearly visible in his work: precise, flat brushstrokes that become textural only on rare occasions, and white borders left unfinished, marked by slight colour smudges, the only areas where control seems to slip. These open edges speak of incompletion, of open doors, and tell a story that only becomes whole when the exhibition is viewed in its entirety. Like a video game, Max moves through the works as a modern-day Hercules, overcoming trial after trial until reaching the final level, where he can defeat his demons and reach the light.

“Nice paintings, but a little too dark… You should paint the light,” his mother tells him. After two days spent reflecting on her words, Scotty Ramon returns to the studio and paints FREE (originally meant to be the cover of Kid Cudi’s album Free). Max is falling, but this time he is neither suspended nor afraid: he is aware. The rare textural brushstrokes reappear in the clouds, as if everything becomes more real once he escapes that two-dimensional nightmare. Looking at FREE, Scotty Ramon finally feels happy. He is now ready to guide others.

This is his call as an artist: to offer hope, to give guidance to people who are still in the struggle. He wants viewers to find answers in his work, to feel connected, less alone. This is why, in 2025, he founded the Big Bro Foundation, with the mission to guide, uplift, and empower young people — especially Black youth — facing mental health challenges, while increasing access to resources and care. In support of the foundation, Scotty Ramon created a series of T-shirts in collaboration with Off-White, with all proceeds donated to the cause.

A remarkably complete debut exhibition — further enriched by a sound piece created specifically for the show and accessible only within the gallery — ECHOES OF THE PAST stands as a strong narrative success with a clear, unembellished purpose. Scotty Ramon lays himself bare, offering his most intimate testimony to give hope to those navigating difficult moments.

Address and contact:

Ruttkowski;68

8 Rue Charlot, 75003 Paris

www.ruttkowski68.com